By — Hansin Kapoor

Abstract

This review offers an interdisciplinary critique of The Gentlemen, examining criminality as an inherited legacy and economic necessity within globalised crime economies. By foregrounding the victim – offender overlap, the series disrupts binary crime narratives and exposes the convergence of legality, privilege, and deviance. Through comparative socio-legal parallels with Bollywood crime cinema, the review situates the text within broader debates on inequality, informal economies, and media constructions of power, morality, and justice.

Introduction

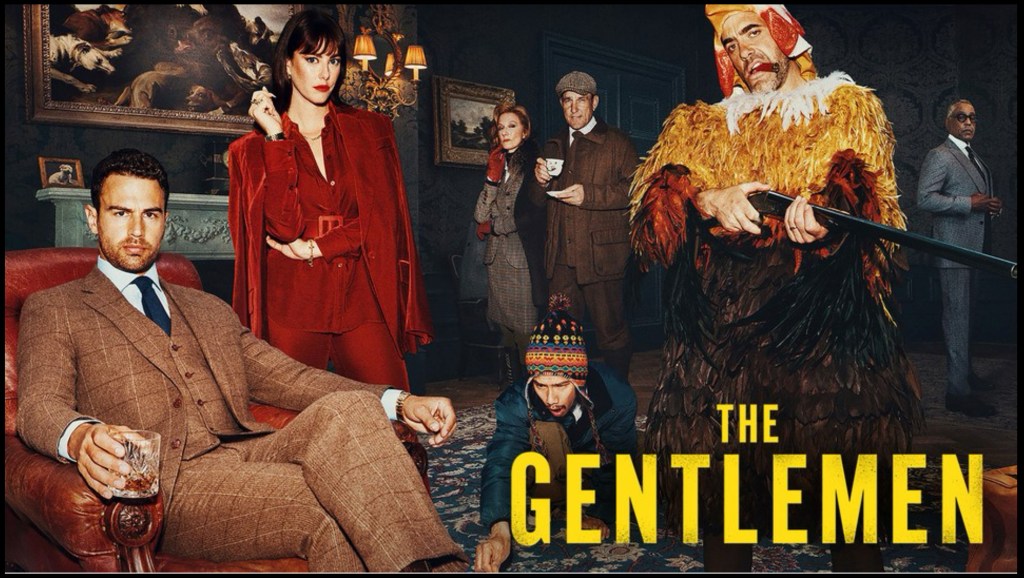

Netflix’s series The Gentlemen (2024) by Guy Ritchie is a dark comedy crime thriller that offers a sharp satire of the intersection of aristocracy and organized crime in modern Britain.

The series follows Eddie Horniman, the protagonist and an estranged army captain who inherits his late father’s country estate. However, what looks to him as an inheritance of privilege soon turns out to be an inheritance of peril when he discovers that his new home is the hub of a lucrative cannabis empire run by the cunning and resourceful lady named Susie Glass, who is the de facto boss of the enterprise in the absence of her father, crime lord Bobby Glass, who’s in prison. While navigating to a new reality, he’s dropped into a world of shifting allegiances, loyalty, rivalries, and power struggles, entangling him in a moral maze where reason and morality are not black and white. His reluctant involvement in the business not only exposes the deep connivance of old money aristocracy with the organized crime running under its umbrella but also highlights how power and privilege moulds modern criminal economies. As the series unfolds, the narrative weaves together themes of legacy, dominance and moral ambiguity, which contrasts the luxury of the aristocratic British gentry with the brutal pragmatism of the criminal underworld.

Organised Crime as a Bureaucratic Enterprise

Organized crime operates with a well-established hierarchical structure, similar to how legitimate bureaucracies appear to function and administer. Donald Cressey, a well-known scholar in 1969, gave “The Cosa Nostra Model” which explains how criminal syndicates function with high position holders such as political leaders, law enforcers, financiers, legal advisors and other authoritarians. This hierarchy ensures efficiency, secrecy, and continuity of operations similar to how corporate entities function. Moreover, Abadinsky describes organized crime as a system where illicit profits or assets are laundered through legitimate businesses, ensuring economic stability and reducing law enforcement scrutiny. Drug networks as examined by Paoli & Greenfield often exploit rural or backward infrastructures to manage and govern operations, taking advantage of minimal oversight and surveillance.

In the series, the Glass Empire is structured very similarly to what these scholars have proposed and discussed. For instance, Susie, who is the de facto CEO, manages and looks after everything while her father Bobby is incarcerated, under her a network of enforcers, financiers and legal intermediaries keep the enterprise running ensuring its smooth functioning. The use of aristocratic estates to hide massive cannabis farms is a common organized crime practice of integrating illicit economies into such legitimate and historical spaces, which are looked as retarded and useless, turning structural obsolescence into a mask for power. The use of financial laundering, bribes to public officials, and encrypted communication is a modern organised crime strategy. The ability of the operation to withstand leadership changes, first Bobby, then Susie, then Eddie, shows the bureaucratic resilience of such criminal enterprises.

Modus Operandi

The Glass Syndicate functions like a well-oiled mechanical system, using legal deception, strategically planned violence, and sufficient modern technology to uphold their dominance and put themselves ahead of their rivals. In order to ensure full secrecy and the plan’s anonymity, they heavily rely on encrypted communication which helps them coordinate actions. Additionally, buying politicians and law enforcement lessens this interference, which is consistent with the racketeering paradigm. According to rational choice theory, violence is not impulsive but rather carefully planned and executed, intimidation and targeted killings act as deterrents. In the series, Susie’s calculated decisions, such as eliminating internal threats and leveraging the protagonist, Eddie’s aristocratic status, demonstrate this approach to deviant activity.

Theories Behind Aristocratic Crime

Merton’s strain theory (1938) also states that when legal means of achievement are restricted, people turn to illegal means to reach their desired ends, which leads to criminal activity. Herein, Eddie first attempts to follow his family’s tradition (conformity), but eventually succumbs to financial constraints and uses illicit means (innovation). It’s noteworthy that he exploits the whole illicit drug empire to safeguard his fortune rather than giving up on his ambition. However, Freddy, the protagonist’s older brother, exemplifies retreatism, which is the complete abandonment of socially acceptable goals and resources. His self-destructive actions and severe drug addiction are indicative of those who distance themselves from expectations when they are unable to handle social pressures.

The series also conveys the idea of white-collar crime, as Elite deviance elaborates on this by demonstrating how members of the affluent or aristocratic class exploit systems in order to evade punishment. Eddie is protected from judicial examination by his aristocratic status since the Horniman estate reflects elite misbehavior in the real world and signifies hereditary wealth based on historical exploitation. In order to avoid legal and other consequences, the wealthy can use their financial and political clout to conceal criminal activity within legitimate and clean legal structures, which is why the drug trade flourishes. According to Young’s (1999) exclusive society theory, elites avoid repercussions while underprivileged populations are subjected to more scrutiny. The working-class criminals risk their lives for little reward, while aristocrats or such similar legacy holders like Eddie Horniman inherit privilege and protection.

Cross-Cultural Parallels

Crime sagas, as we all know, often reflect the socioeconomic circumstances that support organized crime. While Indian crime films like “Gangs of Wasseypur” (2012) examine the effects of “postcolonial disenfranchisement”, this series criticizes the British aristocracy’s involvement with crime. Even though both stories have very different cultures, they are comparable in the way they depict crime because of social injustice, unstable economies, and the shortcomings of both administration and governance.

The criminal enterprise in “Gangs of Wasseypur” is rooted in socio-political exploitation, following the historical grievances of coal miners who became gangsters because of industrialization and political treachery. The film portrays crime as an inevitable part of a corrupt system that restricts the underprivileged population’s access to legitimate means of social advancement, rather than just an individual choice. In a similar vein, “The Gentlemen” critiques the British nobility’s role in perpetuating economic inequality. The way old-money elites keep their wealth through illegal means while putting on a respectable front is exemplified by Eddie Horniman’s inheritance of a drug enterprise concealed beneath a prestigious heritage. Furthermore, “Gangs of Wasseypur” has a strong foundation in postcolonial India, where caste politics and industrialization shape the criminal underworld and depict crime as a reaction to past tyranny, with gangsters hailing from the lower, backward strata, who are excluded from positions of legitimate authority. In contrast, “The Gentlemen” exposes the moral decay of inherited wealth and its complicity in corrupt endeavors by criticizing crime from the standpoint of entrenched privilege because its criminals are not fighting for their lives but rather navigating an established hierarchical system of power. Notwithstanding these distinctions, the folly of law enforcement as an impartial entity is revealed in both stories. Police officers in “Gangs of Wasseypur” are used as puppets by criminal and political forces, brutally policing the impoverished while ignoring systematic exploitation. Similarly, in “The Gentlemen”, law enforcement is depicted as deeply complicit in the operations of the Glass Empire, ensuring that those with wealth and well-known connections remain immune from devastating as well as serious consequences.

Conclusion

The Gentlemen weaves postmodern crime storytelling with a sharp analysis of systemic corruption, power, and social hierarchy, constructing a narrative in which crime is neither exceptional nor aberrant but structurally embedded within governance itself. Set in a world where justice bends toward power, the series blurs the boundary between legality and criminality, portraying organised crime as a rational, bureaucratic, and economically efficient enterprise sustained by elite deviance and institutional complicity. Rather than moralising its characters, the narrative presents crime as a logical response to political and socioeconomic constraints, revealing how structures that protect wealth and privilege actively enable illegal economies. The Glass syndicate exemplifies this mutually reinforcing relationship between lawfulness and criminality, where aristocrats, law enforcement, and political actors operate in tacit alignment. Characters such as Freddy and Susie embody the victim offender overlap, shaped by environments that exploit vulnerability through class marginalisation, gendered power, and state neglect, thereby rejecting simplistic notions of victimhood. Through parallels with Bollywood crime narratives, the series underscores the universality of crime as a product of systemic injustice, exposing law enforcement as a mechanism of control rather than justice. Ultimately, The Gentlemen urges viewers to confront crime not as an anomaly but as an enduring feature of modern governance shaped by inequality and selective morality.

About the Author

Hansin Kapoor is a Criminology student at O.P. Jindal Global University who examines the intersection of criminology and politics within the world of organized crime.

Image Source:https://www.tvinsider.com/show/the-gentlemen/