By — Poorvanshi Tyagi

Abstract

Education and democracy go hand in hand when it comes to human emancipation and development. A major chunk of studies suggests positive correlation of liberal democracies with higher literacy and education statistics. How do education and democracy work in the Indian context? Does the Indian education system leave any space for democratic expression and emancipation? This article aims to analyse the Indian education system and assess its intersection with democratization.

Introduction

When educational reformer John Dewey wrote Democracy And Education, he reaffirmed the significance of the two in the context of human emancipation, specifically emancipation of the mind. He played with the idea that democracy inherently produces space for freedom, and thus the confluence of democracy and education result in freeing of the mind, such that it achieves enlightenment – the ability to think for oneself as Kant defined it. Although ground realities of democratic nations suggest discrepancies in education, it is commonly known that democratic institutions allow education to be a fundamental right to its citizens, one that empowers them to make decisions in the political and civil society. The role of education in a representative democracy extends beyond political participation of the population. Education helps citizens make informed decisions and strengthens the quality of their political involvement with the state. Absence of educational reforms silences those without a voice and equips the state with monopoly over the minds of its population.

With regard to the Indian context, the intersection of education and democracy impact youth employment, power of collective social action, as well as freedom of expression. Evaluation of government intervention in learning pedagogies, university activities, as well as formulation of relevant educational policies is crucial to understanding this confluence.

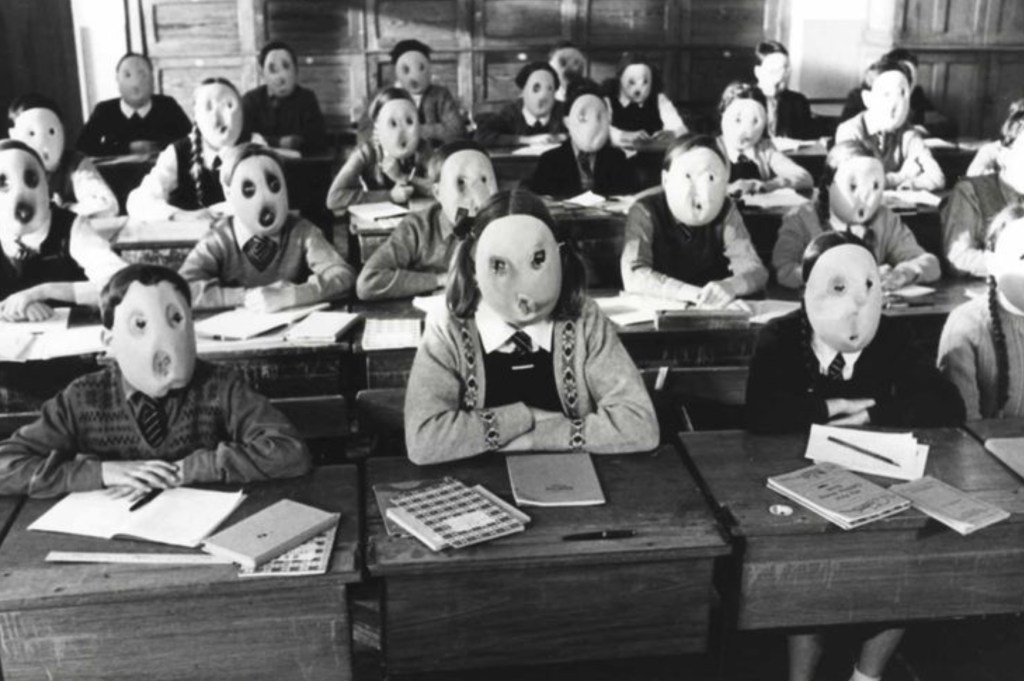

Making Of The Indian Student: Institutionalisation of Control & Discipline

Early childhood development depends as much on schooling as it does on family and immediate environment. As opposed to a space for exploration and nurturing curiosity, school becomes a center of disciplining and moulding young learners into docile subjects loyal to the state. Foucauldian work on discipline provides insight into how transition from old public spectacles of punishment into individual-oriented internalised control has become an integral part of modern education systems. The division of learning phases and sectioning of students into different standards according to age groups provides the state with a framework to govern bodies and reaffirms a sense of control in the minds of students. In his radical work Deschooling Society, Austrian theologian Ivan Illich asserts that schools hinder true learning as they institutionalise dependency and restrict a learner’s autonomy, making them passive recipients of knowledge rather than active participators. Foucault approaches the school system through a focus on objectification of the body and mind as well as internalisation of control. Illich, on the other hand, identified a problem with the systemic culture of learning that schools imbibe. Yet, both help us understand the physiological and cognitive constraint schools impose upon students through their disciplinary regulations and how fatal it can be to build an adequate learning environment.

The average urban Indian student experiences a school culture which is marked by disciplinary procedures such as punitive actions against ‘non-affirming behaviour’ such as talking to peers in the classroom, interacting in regional languages as opposed to English, and so on. It simultaneously rewards ‘obedient behaviour’ such as high grades and keeping quiet. Such classroom culture governs bodies as it restricts motor movements and subsequently aims to produce compliance over critical learning.

Pedagogy similarly plays an important role as a form of control over young minds as common pedagogic tools such as dictation of notes by teachers produces boundaries between what is ‘thinkable and legitimate to be taught’ versus what is ‘unthinkable and must not be reproduced’. The institutionalisation of discipline and control in schools paralyses learning. It relies on ‘reproduction’ as the focal point of learning and punishes experiential learning. It restricts emancipation of the mind as Dewey’s belief in democracy suggested. Such disciplinary practices have an impact on democratic capacities of a student as an obedience-oriented pedagogy limits active critical participation when it comes to democratic expression. Critical thinking goes unvalued since the major objective pertains to docility and control.

Schools As Centres Of Knowledge Production

The state envisions schools as important centres of imparting value-based and moral education. Schools and universities not only impart knowledge but become active participators of knowledge production. School curriculum and syllabus decides what is meant to be taught and what must remain outside of the student’s eye. In this context, education is more often than not corrupted by state politics – moulding facts and realities as it deems fit. This is integral to the creation of national identities and a national imagination that fits narratives of the state. This process continues to harm the marginalised and dispossessed as knowledge production highlights certain perspectives and erases others. For instance, Ranjit Guha’s remarked on how domination of colonial-elitism in the historiography of Indian nationalism hides important ways of knowing the colonial project through peasantry and the subaltern classes.

Curricula-building and syllabi in Indian schools and higher educational institutions is a pivotal threat to promoting democratisation as it continues to restrict flow of knowledge and information while simultaneously increasing risk of disinformation. Educational policies actively shape collective memory and political identity. They hide critical discourse and consolidate state-sponsored information as facts that are – common and gospels of truth. The removal of chapters on Mughal Empire from class XII textbooks by National Council Of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) in 2023 was justified as a syllabus rationalisation to ease off students from extra burden. It, however, was a decision lauded by right-wing leaders as it is part of a larger project to erase memory and distort the history of the subcontinent. Similarly, a recent change in the titles of English textbooks to Hindi titles undertaken by NCERT under National Educational Policy (NEP) 2020 has sparked debate over its attempt at homogenising national identities through erosion of linguistic plurality. The questionable announcement of including Bhagavad Gita as a text for all classes (6-12) further puts hegemonic knowledge systems to the forefront of education politics in India, producing biases when it comes to the practice of secularism, and inadvertently shrinking the capacity for democratic and critical learning.

Party Politics & Freedom Of Expression in Universities

Education must help equip one with social responsibility and encourage sensitivity to issues around them. Education as a space for collective social action can help involve youth in active political participation to raise their voices, rethink majoritarian discourses and enable future changemakers. Collective action such as strikes and protests allow students a space of resistance and rebellion, one that can be used as a tool of dissent against the state and its policies. It encourages freedom of expression, fundamental to a student’s life. Disputing student protests and open speeches seek to undermine the value of education itself.

Collective resistance and solidarity are active agents of a functioning democracy. Theorists of participatory democracy suggest that democracy extends beyond voting rights and exists in collective decision-making and solidarity in socio-economic realms such as the classroom, the household, and workplace. Student activism in universities becomes not just a site of resistance and rebellion but also a form of active democratic participation.

Collective action in Indian universities is more often than not suppressed by the state through threat and/or intimidation. When political parties seek to build national identities as a part of their own ideological agendas, anti-party discourse is perceived as seditious and anti-national in nature. This not only strips opposing viewpoints from their social and politico-moral value but also takes away student voices and suppresses critical learning for the bigger purpose of maintaining law and order. The blatant use of lathi charge on students participating in peaceful protests, of which the 2019 incident of violence incited upon JNU students engaging in a peaceful march from University to Rashtrapati Bhavan in 2019, is a prime example and hints towards the deteriorating state of participatory democracy and freedom.

Conclusion

Education’s interaction with democratization and democratic expression extends beyond political involvement. It moulds learning experiences and shapes how a student would come to interact with the world around them. India’s education system allows relatively less space for development and capacity building as it continually interacts with undemocratic social and political forces, which undermine capacities necessary for youth development. Youth culture, however, differs from the dominant socio-political milieu, and thus constantly attempts to reject major educational drawbacks through unlearning and re-learning processes such as devaluing school work. Schools and universities in India, nonetheless, continue to operate within oppressive frameworks of discipline, control, and knowledge production.

About The Author

Poorvanshi Tyagi is a second year student at Jindal School Of International Affairs, O.P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat. She is currently pursuing a Bachelor’s in Global Affairs and a diploma in Literature. She is a published poet and an avid reader. She is open to research opportunities in the field of education, sociology and critical theory.

Image Source: https://in.pinterest.com/pin/139893132155242564/