By – Hansin Kapoor

Abstract

This article critically compares the prison law frameworks of Japan and India, examining the evolution of their statutes and prison manuals in relation to prisoners’ rights and rehabilitation. While Japan’s system, historically marked by strict discipline, has moved toward a rehabilitative model, India’s prison regime, rooted in colonial legislation, operates through state prison rules supplemented by the Model Prison Manual, 2016. When assessed against international standards, particularly the UN Nelson Mandela Rules, the article analyses how both systems balance punishment with dignity, and custody with reform, in law and practice.

Introduction

Prisons worldwide face the tension between punishment and rehabilitation, with systems evolving under social and legal pressures. Japan’s penal system, administered by the Ministry of Justice’s Correction Bureau, has long been noted for strict rules and emphasis on conformity. In contrast, India’s prisons are governed by colonial-era laws (e.g. Prisons Act, 1894) and numerous state manuals, with recent efforts (Model Prison Manual 2016) to promote uniform reforms. This analysis compares these frameworks, paying special attention to how each addresses prisoner rights and rehabilitation, and how they measure up to the revised UN Standard Minimum Rules (Nelson Mandela Rules).

Historical Evolution of Prison Systems

Japan’s modern prison system originated in the Meiji era, modelled on European systems, with a patchwork of local rules consolidated under central control by 1900. Early volumes of the “Kangoku Shokisoku” (Prison Rules and Legislations, 1890s) document the exhaustive regulations for prisons and guards, reflecting a culture of rigid discipline. The core Prison Law, established in 1908 (later revised), focused on security, labor, and order. Over time, criticism emerged that Japan’s unyielding regime of rising inmate complaints needed reform to meet international norms. In the 2000s, Japan enacted new laws, for example, the 2007 Offender Rehabilitation Act, explicitly aiming to prevent recidivism and reintegrate offenders as “self-reliant” members of society. Similarly, India inherited British colonial prison laws (Prisons Act 1894, Prisoners Act 1900) and state-specific jail rules. Early reform committees (1980s) urged a national approach, but prisons remain a State subject under the Indian Constitution. Over the decades, court decisions (e.g. Sunil Batra v. Delhi, 1978 and others) forced improvements in conditions. In 2016, the Government approved a Model Prison Manual to guide uniform prison reform across states.

Japanese Prison Laws and Reforms

Today Japan’s prison regime is governed by laws such as the Act on Penal Detention Facilities and the Offender Rehabilitation Act. These laws emphasize inmate classification, labor, education, and parole. Official translations of Japanese law explain that treatment and rehabilitation of inmates are primary goals: the 2007 Offender Rehabilitation Act’s Article 1 states its purpose is “to provide proper treatment to persons who have committed crimes… and assist them to become self-reliant as sound members of society… thereby protecting society and enhancing the welfare of individuals”. Traditionally, Japanese prisons required most inmates to work and had strict discipline. However, recent reforms (as reported in 2025) “place greater emphasis on rehabilitation over punishment” as Japan addresses a relatively high recidivism rate. These reforms encourage education, counseling and skill training within prisons. The Ministry of Justice’s Correction Bureau also highlights inmate education and reintegration in its policies. Nevertheless, observers note Japan’s system remains closed and bureaucratic, unless Japan aligns prisons with international standards, prisoner grievances will persist.

Indian Prison Manuals and Laws

Prison governance in India is complex because it is shaped by a layered federal structure, a lingering colonial legal legacy, and deep administrative fragmentation as each state enacts its own prison rules or manuals under the general framework of central acts, examples include the Tamil Nadu Prison Rules (1983), the Assam Prisons Act (2013), and manuals in Karnataka, Maharashtra, among others. Recognizing the unevenness, the central government developed a Model Prison Manual (2016) as guidance. The 2016 Manual, approved for all States and Union Territories, “provides detailed guidance on all aspects of prison and correctional administration”. It contains dedicated chapters on “After-Care and Rehabilitation”, “Education of Prisoners”, and “Legal Aid” and likewise on “Medical Care” and “Welfare of Prisoners” (covering health, counseling, mental well-being). The Model

Manual defines key terms in line with existing law, for instance, a “Convict” is any prisoner under a criminal sentence, and an “Under-trial” is one awaiting trial. States have begun aligning with it, for example, Karnataka’s 2021 Prisons & Correctional Services Manual explicitly incorporated many Model Manual provisions. However, local statutes still show legacy issues. A 2024 Prison in India report by the Supreme Court of India found that many state manuals retain caste-based work divisions for e.g. specifying that barbers or sweepers be drawn from certain castes. The Supreme Court has struck down such provisions, in Sukanya Shantha v. Union of India (2024), the Court held that any prison rule mandating caste-based discrimination or labor divisions is unconstitutional. This indicates a gap between historical practice and modern rights norms in Indian prison law.

Prisoners’ Rights and Rehabilitation in Japan

In Japan, prisoners have some legal protections (for example, courts have begun entertaining inmate complaints), but rights are limited. The system allows solitary confinement and strict discipline, which human rights advocates say can violate standards of humane treatment. On the other hand, Japan’s crime rate is low and prisons are not overcrowded. Access to rehabilitation programs has increased: recent laws and policies stress vocational training and community “volunteer probation officers” (“hogoshi”) to support former inmates. Japan also participates actively in international justice forums. Its officials publicly endorse UN standards like the Nelson Mandela Rules as “clear guidance” for improving prison conditions. In practice, Japan has been moving toward ratcheting up social reintegration efforts. For example, as noted above, the 2007 Offender Rehabilitation Act’s language reflects modern penology. Still, some critics say Japan lags in areas such as judicial review of detention.

Prisoners’ Rights and Rehabilitation in India

Indian law guarantees that prisoners, despite loss of liberty, retain basic rights (the Supreme Court emphasizes they are “entitled to all basic human rights, human dignity and human sympathy” even in confinement). The Model Prison Manual (2016) explicitly echoes international law (ICCPR Article 10) in treating reformation and rehabilitation as the “essential aim” of prisons. It emphasizes legal aid, skill training, education and after-care programs for inmates. Many state manuals likewise provide for similar programs. For instance, Tamil Nadu’s rules require vocational training and probationary committees. However, India’s prisons suffer chronic overcrowding and undertrial backlogs with often over 70% undertrial prisoners and conditions that are widely criticized by rights groups. Judicial and policy interventions like bail rules, legal aid cells aim to reduce these problems. India also ratified major treaties like the ICCPR, incorporating non-cruelty and dignity mandates. The Union government now actively promotes the Mandela Rules, as seen in training workshops and collaborations for e.g. a 2025 UNODC consultation in Assam on dignity, health and Mandela Rules.

Nelson Mandela Rules and Comparison

Both systems are increasingly measured against the UN’s revised Standard Minimum Rules for Treatment of Prisoners (the “Nelson Mandela Rules”). These rules (adopted 2015) stress dignity, humane conditions, health care, and the goal of rehabilitation. India explicitly uses these as a benchmark, the MHA and UNODC promote them in reform programs. Japan’s government likewise cites Mandela Rules alongside regional standards, emphasizing them in diplomatic statements. In practice, both countries have strides and shortfalls relative to these norms. Japan has excellent security and health care but has faced criticism over limited family contact and lack of sentence review as raised by the Human Rights Watch. India’s laws, on paper, provide for health, education and complaint procedures as reflected in the Model Manual, but implementation is uneven as many jails are overcrowded and under-resourced. The Supreme Court of India has often invoked human rights norms in rulings on prison conditions. Comparatively, Japan’s reforms seem focused on processes like classification and parole, whereas India’s are tackling both systemic issues and massive inmate populations.

Conclusion

Japan and India present contrasting prison systems shaped by history and governance. Japan’s approach has long prioritized control and conformity, but recent policies mark a shift toward rehabilitation, aligning with its Offender Rehabilitation Act and global norms. India’s prison laws are decentralized but are being harmonized by a comprehensive Model Prison Manual, reflecting a principled view that prisons must focus on reformation and human rights. Both countries recognize the Nelson Mandela Rules as a benchmark for humane treatment. Yet practical challenges remain. Japan must adapt traditional practices to modern human rights expectations, while India must overcome resource and legal gaps such as caste bias and overcrowding to realize the rights stipulated in its laws. My article underscores that history and culture influence prison policy, but international standards are increasingly shaping reforms in both nations.

About the Author

Hansin Kapoor is a final-year student of B.A. (Hons.) Criminology and Criminal Justice with research interests in criminal justice and comparative penal systems.

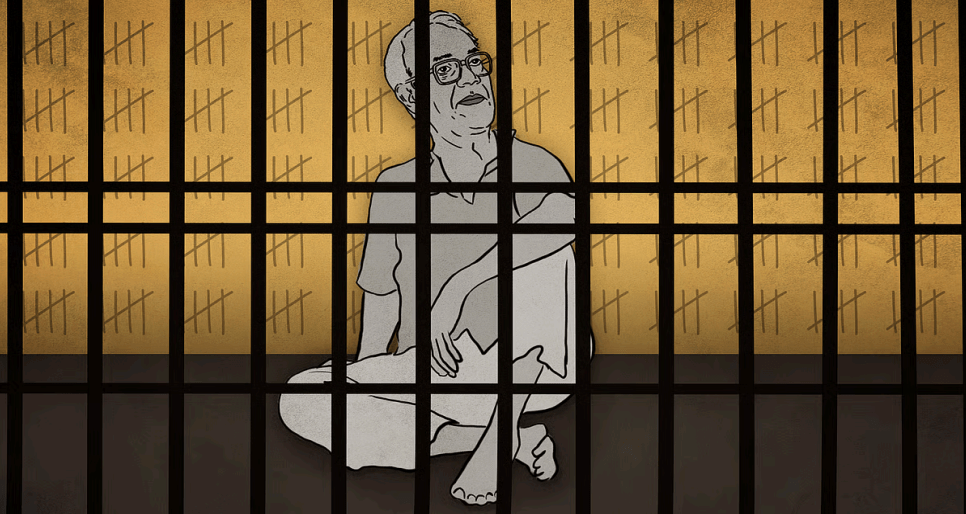

Image Source – How Stan Swamy spent his last months in jail