By – Rianne Michael

Abstract

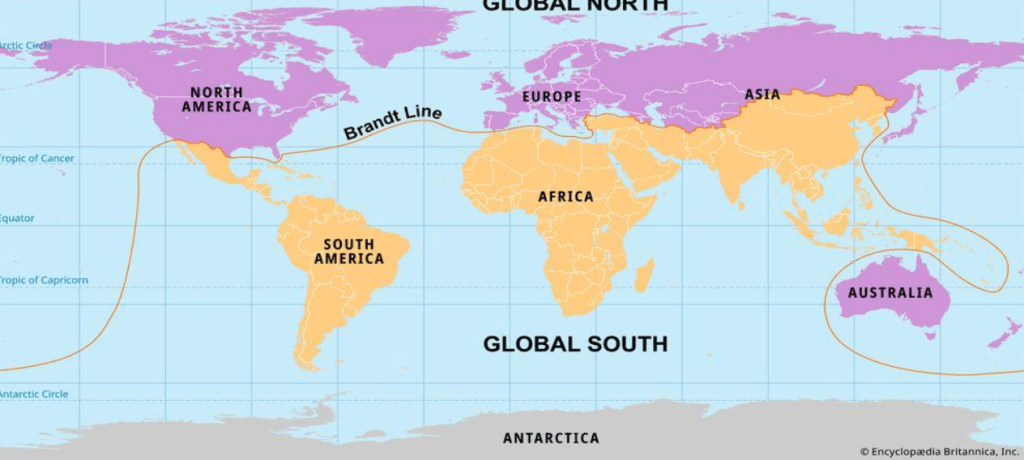

Eurocentric knowledge has historically functioned as the major epistemic framework, creating the view that Western historical experience is universal leading to marginalization of knowledge from the Global South and Indigenous communities. This article argues that Eurocentric knowledge is not also produces structural boundaries of inclusion and exclusion that shape the global order, policies, and international institutions. By examining the foundations of International Relations, which is grounded in the Eurocentric assumptions that knowledge production should ideally flow from the West and is universal, the paper demonstrates how the coloniality of knowledge constrains agency in the Global South. Drawing insights from TWAIL and decolonial scholarship, the article advocates using epistemic pluralism as a corrective measure that decentralizes Western knowledge without rejecting it and allows Indigenous and Global South epistemologies to co-exist while creating global norms. This reconfigures International Relations as a context-sensitive discipline that restores agency to the Global South.

Introduction

Knowledge plays a major role in shaping how global politics is understood, governed and transformed. In International Relations, knowledge is structured through a hegemonic framework, creating boundaries of inclusion and exclusion, due to which knowledge of dominant groups is treated as universal and the subordinate groups are reduced to objects of this knowledge. This coloniality of knowledge is embedded within hierarchies of gender, class, race and sex that deem the West as superior, reproducing colonial patterns of global inequality. This Eurocentric framework leads to the rejection of knowledge from the Global South and Indigenous groups. Today’s global system of governance is facing a crisis of legitimacy due to growing distrust of the Global South in international institutions as they are structurally bias and underrepresent the South. The rise of forums from the South such as the New Development Bank, BRICS and other South cooperation frameworks show a deeper epistemic contestation about whose knowledge and priorities shape global norms. Epistemic debates are not just confined to academia but are directly linked to fairness and effectiveness in global governance. When international institutions function on the basis of Eurocentric thought which treats European history is treated as universal, serving as a model through which the rest of the world is evaluated, it leads to exclusion and undermines cooperation of nations. This brings up the question of whose knowledge counts and how global governance can be reimagined. This paper argues that Eurocentric knowledge production that is institutionalized in IR through international institutions and policies leads to marginalization of knowledge from the Global South, and this requires a shift by situating Western knowledge as one epistemic tradition among many rather than letting it constitute a universal benchmark, thereby decolonizing knowledge and creating an inclusive global order.

Coloniality of Knowledge and The Myth of Eurocentric Universality

The founding concepts of IR are rooted in Eurocentric knowledge and thinking that came about after colonialism and imperialism. Western knowledge provides an ideal template to which all other nations are required to follow and presents itself as universal despite being rooted in European historical experience. This lies in Western knowledge’s claim to universality. This consequent concentration of knowledge production coming from Western academic institutions strengthens this single-axis formation and claim for universalism. The global production of knowledge being Eurocentric leads to alignment of rationality, science and modernity with European principles while marking non-European knowledge inferior. This is depicted in the case of Human Rights, where individual rights assume an individual mainly has rights such as freedom of speech, religion and privacy, framing them as individual entitlements and marginalizing that Global South societies where land is collectively owned, identity is subjective based on tribe or clan and duties like in the Adivasi communities. Therefore, the result of this epistemic ordering leads to naturalizing Western principles and history, reframing global inequalities as internal failure of the Global South rather than looking at it as outcomes of colonial exploitation. Indigenous principles that are grounded in ecology and collective community knowledge are dismissed as they are not of Western thought.

Eurocentric Assumption of Knowledge Production Distorting Global Order

The coloniality of knowledge becomes a global problem when the Eurocentric assumptions that all societies lie on the same path of one development trajectory culminating in Western modernity are the underlying principles followed in global governance and by international institutions. In International Relations, Third World countries and the Global South are not allowed to exert agency, although the new states were independent according to International Law. Creation of binary categories in the global order, such as West and East,Centre and periphery and first and third world reinforce global difference through simplification, making the West embody “great tradition” while the Global South has “little tradition”. Gayatri Spivak proposes a notion of strategic essentialism that allows the subaltern to represent themselves based on their shared identity that can function as a political strategy to forget the colonial differences that continue to be present in the global order.

TWAIL scholars such as B.S Chimni demonstrate that this Eurocentric logic is institutionalized in international law and governance as international institutions create universal standards derived from Western historical experience while ignoring the situation of the Global South in terms of their uneven development and different political order. Through institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organization and the World Bank, international law enforces the uniform standards that take upon Western models of markets, development and statehood. For example, the TRIPS agreement globalizes Western concepts of property thereby forcing Third World states to enforce intellectual property rules that undermine their local knowledge, public health and autonomy. This reproduces a hierarchy in the global order and continues to misrepresent and take away the agency of the Global South. This depicts that Eurocentric knowledge actively shapes the global order by determining the way International Relations is formed, leading to constraints in political imagination and the removal of agency of the Global South and indigenous knowledge systems.

Dismantling the Hierarchy through Epistemic Pluralism

If Western knowledge has shaped global order by marginalizing the Global South, the question is not one of critique and rejection but reconstruction. Segun Charles Sule argues that political decolonization did not dismantle epistemic domination; instead coloniality continues to persist through universalization of European knowledge systems in academia, policymaking and international institutions. A solution that is meaningful should not just critique the current system but focus on how alternative systems of knowledge can be reintegrated without rejection of Western knowledge. The first step towards epistemic change lies in challenging the assumption that Eurocentric knowledge is universal and applies in all spheres, irrespective of the context. Alternative systems of knowledge, such as Indigenous Knowledge Systems, are not excluded because they lack validity but because they do not follow Western norms and principles. These systems should be reintroduced in order to reject the idea that there is a single epistemic centre that forms the global order. This change would directly affect the way in which international relations and global governance function. Knowledge should be treated as contextual rather than universal, leading to the removal of uniform policies across different social and historical contexts. There needs to be a contextual shift in what knowledge is produced and authorised within International Relations. One pathway is epistemic pluralism, which holds that no single epistemological tradition can have universal authority in the global order. It refers to the recognition of multiple epistemic frameworks of knowledge as valid and relevant in the global framework addressing broader questions of efficacy and impact in the social context. This means that Eurocentric knowledge requires decentering. Methodological pluralism challenges who produces knowledge and what is universal. Institutional change follows from this by becoming more inclusive and legitimate by recognizing multiple epistemologies as valid. Such a change would allow indigenous and Global South knowledge rather than using them merely for data.

This transformation would have many implications for international institutions, as policies and bodies would be structured keeping in mind the diverse economic and social arrangements. Such as climate governance that could be reshaped by using indigenous ecological knowledge as a major manner to design environmental policies of the world. Decolonizing International Relations by embracing epistemic pluralism, making it a discipline that recognizes the Global South as an agent playing a major part in the future of global norms, institutions and structures.

Conclusion

Eurocentric knowledge continues to shape IR by defining what counts as legitimate and rational knowledge, thereby making it universal and leading to Global South knowledge as incomplete and irrational. This hierarchy affects much more beyond academics, as it is institutionalized through international law and policies, where context is not taken into consideration, imposing a uniform standard. The solution requires dismantling the monopoly of Western knowledge and using epistemic pluralism to offer a path for knowledge from the Global South. An IR grounded in epistemic pluralism would not only correct colonial differences but also expand the discipline’s capacity to respond to challenges in a more diverse manner, thereby creating a better functioning global order.

About the Author:

Rianne Michael is currently doing her BA LLB at Jindal Global Law School. Her interests lie in travelling, reading and discovering new food in the city.

Image Sources: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Global-North-and-Global South#/media/1/2256393/319480