By – Karishma Jain

Abstract

India’s investment policy has shifted in response to disruptions in global supply chains, intensified competition in critical technologies, and a growing recognition that foreign capital can carry strategic implications beyond economic value. While attracting foreign investment remains central to India’s development strategy, the State has become increasingly attentive to questions of control, dependence, and technological self-reliance in sensitive sectors. Recent reforms in the space sector through the Indian Space Policy 2023 and proposed legislative changes in nuclear energy reflect this recalibration. This article examines the limits of India’s investment openness in strategic sectors, using space and nuclear energy as case studies to assess how foreign capital can be accommodated without diluting sovereign control or long-term technological autonomy.

India’s Geoeconomic Turn in Investment Policy

During the post-1991 period, India’s foreign investment regime was shaped by capital scarcity and the need to integrate with global markets. Foreign direct investment was treated as an unqualified good, which was capable of delivering growth, technology transfer, and efficiency gains. Over the last decade, however, this policy context has altered in important ways.

With global capital flows becoming increasingly entangled with strategic competitions, India is now among the world’s largest recipients of foreign investment.Technologies that once appeared purely commercial, such as satellites, advanced manufacturing, and data infrastructure, now have clear security and geopolitical implications. As a result, foreign capital is no longer treated as politically or strategically neutral.

This shift has led policymakers to reassess the long-standing assumption that all foreign investment advances national interests equally. The introduction of Press Note 3 (2020) by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade requires government approval for investments from countries that share a land border with India, highlighting the increasing focus on strategic screening. The reforms in space and nuclear energy must therefore be understood against a broader geoeconomic backdrop rather than as isolated sectoral changes.

The Space Sector: Liberalisation with Regulatory Control

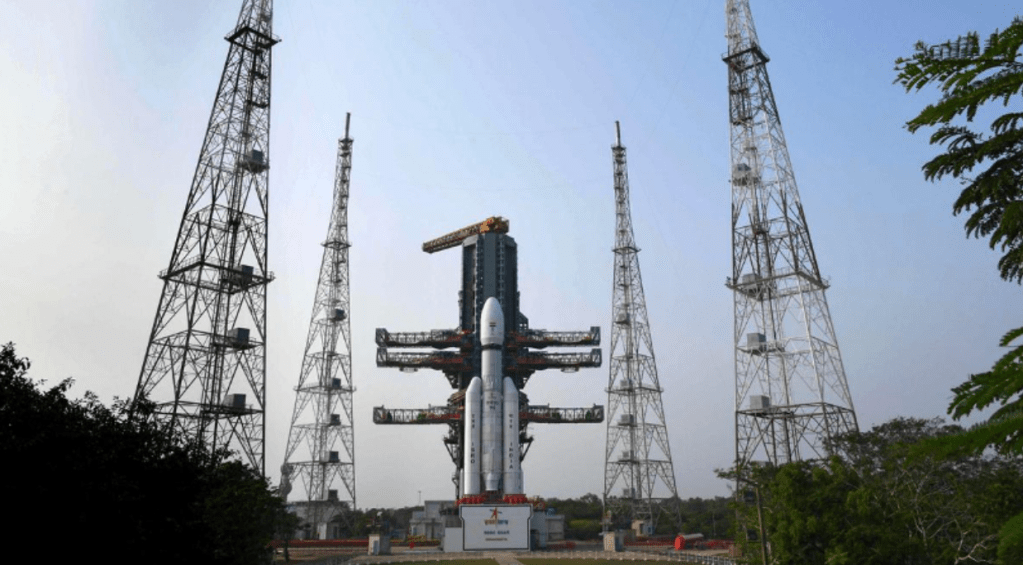

The space sector offers the clearest illustration of India’s evolving investment strategy. Historically, space activities were almost entirely conducted by the Indian Space Research Organisation, with minimal private participation. This began to change with the creation of the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe) in 2020. The shift was formalised through the Indian Space Policy 2023, which explicitly recognises private entities as participants across the space value chain. This includes satellite manufacturing, launch services, ground infrastructure, and downstream applications. Corresponding amendments to India’s foreign investment framework under the Foreign Exchange Management Act now permit up to 100 percent foreign direct investment in the manufacturing of space components and systems, and up to 74 percent foreign investment in satellite-related activities under the automatic route, with higher levels subject to government approval. The consolidated policy position is reflected in official notifications hosted on the Government of India’s e-Gazette portal.

These reforms are intended to channel foreign capital and expertise into India’s emerging private space ecosystem while positioning Indian firms within global production and services networks. Industry projections published by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) suggest that these measures could significantly expand India’s participation in the global space economy.

At the same time, liberalisation remains carefully bound. All space activities are subject to authorisation and supervision by IN-SPACe. Consequently, the State continues to retain control over critical functions such as orbital slot allocation, frequency management, launch approvals, and the handling of sensitive data. Moreover, strategic missions, defence-related satellites, and applications implicating national security remain firmly within the exclusive domain of the government. In effect, India has liberalised commercially viable segments of the space sector while retaining decision-making authority over functions with strategic or security consequences.

Nuclear Energy: A Sector at the Edge of Openness

Nuclear energy presents a sharply contrasting picture. Under the Atomic Energy Act, 1962, nuclear power generation has remained the exclusive domain of state-owned enterprises, with foreign participation limited largely to technology supply arrangements and intergovernmental cooperation.

Recent policy discussions and government statements indicate an intention to revisit this framework to enable limited private and foreign participation in civil nuclear power generation, particularly to support India’s clean energy transition. These developments have been communicated through official releases of the Press Information Bureau. However, even under the proposed reforms, clear structural limits are envisaged. Strategic components of the nuclear fuel cycle, including enrichment, reprocessing, and waste management, are expected to remain under exclusive government control. Furthermore, regulatory oversight is to be strengthened, and liability provisions recalibrated to ensure public safety and compliance with non-proliferation obligations.

This approach reflects a deliberate policy choice grounded in the strategic character of nuclear technology. Unlike space, where commercialisation has proceeded rapidly and where risks can be managed through licensing and post-entry regulation, nuclear energy involves irreversible consequences in terms of safety, environmental impact, and international obligations. This, essentially, justifies a qualitatively different threshold for openness. The continued insistence on state control over the nuclear fuel cycle and regulatory authority should not be viewed as institutional inertia, but as an acknowledgement that certain forms of technological dependence are incompatible with long-term sovereignty. While limited foreign participation may help bridge capacity and financing gaps, especially in the context of clean energy goals, delegating control over core nuclear functions would fundamentally alter India’s strategic posture. In this sense, India’s cautious approach underscores a broader principle: that in sectors where risk is systemic and non-reversible, the costs of over-liberalisation may far outweigh the benefits of accelerated capital inflows.

Screening, Safeguards, and Institutional Design

India does not operate a single, centralised foreign investment screening authority comparable to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS).

Instead, it relies on sectoral caps, approval routes, and executive discretion to regulate investment in sensitive areas. Investments in space and nuclear energy are subject to layered scrutiny involving sectoral regulators, security agencies, and the central government.

This approach is broadly consistent with international practice. The European Union’s investment screening framework, which enables Member States to assess foreign investments that may affect security or public order, reflects similar concerns regarding strategic dependence and technological control. India’s distinctive feature lies in its preference for sector-specific regulation rather than a unified national security screening statute.

The more consequential question, however, is not whether India should adopt a unified screening authority, but how predictable and legible its existing screening processes are for investors in strategic sectors. While sector-specific regulation allows for contextual expertise, its heavy reliance on executive discretion risks creating uncertainty around timelines, criteria, and outcomes of approval. As strategic sectors increasingly rely on long-term, capital-intensive investment, procedural clarity may become as important as substantive control. Strengthening transparency and process discipline within the current framework could therefore enhance institutional credibility without compromising strategic autonomy.

Conclusion: Defining the Limits of Openness

India’s recent investment reforms signal a deeper transformation than a mere recalibration of openness. They reflect an effort to rebuild the State’s bargaining position in an international investment environment where capital is abundant but asymmetrically powerful. By structuring access to strategic sectors around control points rather than ownership alone, India is attempting to reverse a long-standing dynamic in which investment terms were largely dictated by market pressure rather than institutional design.

The divergence between space and nuclear energy illustrates that India is no longer pursuing a single theory of openness. Instead, it is experimenting with differentiated governance strategies based on the nature of technological risk, the reversibility of dependence, and the costs of regulatory failure. This suggests an emerging recognition that not all forms of foreign participation are equally developmental, and that some may weaken, rather than strengthen, long-term strategic capacity.

The success of this approach will ultimately depend less on formal policy thresholds and more on institutional competence. If regulatory authorities can actively shape technology transfer, domestic capability building, and compliance over time, strategic openness may enhance autonomy rather than erode it. If not, openness risks becoming passive exposure rather than a tool of statecraft. The defining question, therefore, is not how much foreign investment India should permit, but whether its institutions are equipped to govern capital as a strategic resource rather than merely accommodate it.

Authors Bio

Karishma Jain is a fourth-year law student from Jindal Global Law School and a member of the Economics and Finance Cluster of Nickeled & Dimed. Her academic interests lie in international trade and investment law, with a particular focus on investment regulation, strategic governance, and the intersection of national security and economic policy.

Image source: X/@isro via PTI Photo