Book review – Pachinko by Min Jin Lee

By – Apoorva Lakshmi Kaipa

About the book/ Abstract

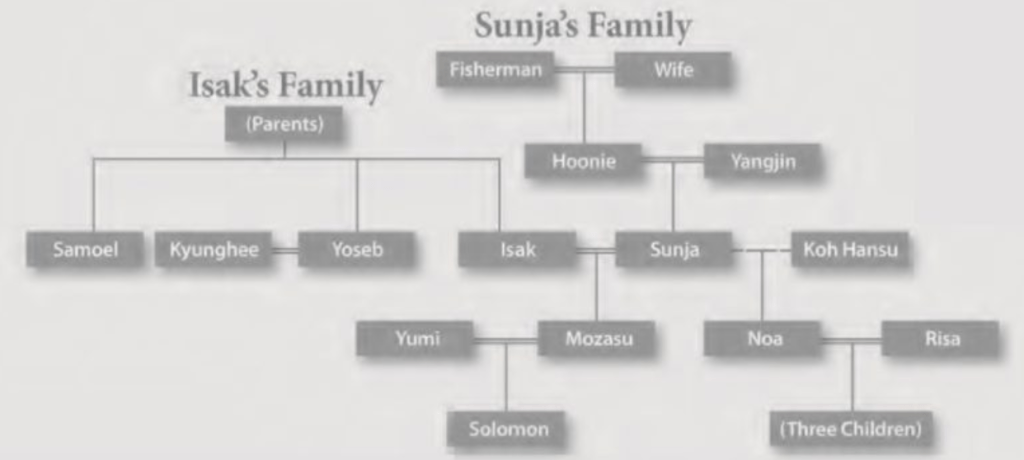

The book is a family saga that spans the years 1910-1989. It begins with Yangjin marrying into a family and follows her daughter Sunja, Sunja’s sons Noa and Mozasu, and Mozasu’s son Solomon. It beautifully captures the generational changes through their personal turmoil, living in the politically charged environments of the times of the two world wars and the Korean War. Sunja, pregnant with the child of an older married man, Koh Hansu, married Beak Isak and immigrated to Japan to give her child a better life and a father. The story unfolds from the choices made by Sunja over time for her safety and for her family’s survival and betterment. The novel explores the themes of migration, survivor’s shame, labour, and structural discrimination. This article will focus primarily on Zainichi Koreans while briefly acknowledging other marginalised communities in Japan. Though this book is a work of fiction, the political narratives and the broader themes are deeply rooted in the real world, and hence, I will be using the book as the north star to dive deeper into the everyday lives of people dealing with discrimination and prejudice.

Introduction

Pachinko (파친코) by Min Jin Lee is divided into three books: Homeland, Motherland and Pachinko. While the author is Korean and was written in English, Pachinko is a novel about Japan just as much as it is about Korea. Let’s go back in history and see why and how this came into place. Since Japan started colonising empires, immigration and emigration have taken place extensively. Lee uses intimate family narratives to expose structural discrimination inside Japan, especially against Zainichi Koreans. There were two options given to Koreans residing in Japan: either adopt a Japanese identification in the form of naturalisation (which was legally difficult) or have the Zainichi status, which means that they keep their own nationality and merely reside in Japan (often involuntarily and inherited). This article examines the novel across major historical periods from Japanese colonisation to late twentieth-century corporate Japan. Marginalisation in Japan has not been episodic or accidental but cumulative and institutionally backed for decades. Discrimination was produced by laws, citizenship regimes, labour markets and social norms. Pachinko, while a work of Fiction, operates as a social archive. It shows everyday effects of policy implementation like housing work, names, schooling, while capturing the daily narratives and the emotional costs of shame, silence and survival methods.

(The main character’s family tree)

Image Source : https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/contextualizing-min-jin-lees-pachinko/

Colonial Origins of Marginalisation

(1910-1945)

Japan formally annexed Korea in 1910. Korean and Japanese officials signed the treaty, which would lead to the erasure of Korean culture, erosion of Korean sovereignty and the end of Korea’s ancient Choson Dynasty. In Pachinko, Sunja’s move to Japan reflects the colonial displacement. It was not voluntary migration that had occurred; it is emphasised multiple times in the book that staying on Korean land would not do them any good. Yangjin (Sunja’s mother) tells her family that the owners of the house were forced to sell it to the government officials, and her helpers were taken to faraway ‘factories’ for better work. While Lee doesn’t explicitly tell what the work was, it is alluded to multiple times that when government officers offer women high-paying jobs in factories, they must not go, as it is not safe, giving us a hint that it might be sexual slavery by the Japanese military or “comfort women”. Koreans were coerced into migrating to Japan as industrial labourers and wartime workers, and when these Koreans arrived in Japan, they were marked as colonial subjects, never seen as equals.

Colonial ideology framed Koreans as inferior and backward. They were seen as useful labour but always shown to be disposable. Yosoeb’s job at a cookie factory displays the fear of losing a job since labour was cheap and jobs were limited; the replaceability of workers was very high.

“They got off at Ikaino, the ghetto where the Koreans lived. When they reached Yoseb’s home, it looked vastly different from the nice houses she’d passed by on the trolley ride from the station. The animal stench was stronger than the smell of food cooking or even the odours of the outhouses.” (Page 103) This quote also emphasises the ghettoisation, segregated housing that Koreans faced. Spatial segregation became a visible manifestation of the racial hierarchies present.

Post-War Japan and Legalised Exclusion

(1945-1960s)

The end of the War brought an end to the empire but not an end to discrimination. Even after Japan left Korea, the Japanese still had colonial policies to reinforce homogeneity and prevent cultural integration. While Japan lost its empire after WWII, Koreans lost their legal belonging. This brought the introduction of the Alien Registration System. This created a sense of permanent exclusion amongst immigrants in Japan. Koreans were no longer colonial subjects but stateless outsiders now. Survival depended on informal economies and community networks. In Pachinko, Hansu explicitly tells Sunja and her family that they survived the war because of him; Hansu’s money and connections ensured Yoseb’s survival.

Koreans were funnelled into dangerous jobs, which were deeply stigmatised and considered to be of low status. When Sunja’s family stayed at a farm to be away from the war and its consequences, they were given manual labour. Once Sunja’s kids, Noa and Mozasu, got older, they always had to work to defy the stereotype placed on Koreans. Mozasu started working in a pachinko parlour to gain economic success. But this also led to social exclusion. The pachinko business was seen as a low-status work, symbolising that wealth did not translate into acceptance.

Image Source : https://www.messynessychic.com/2017/09/13/these-fabulous-vintage-japanese-slot-machines-are-a-collectors-dream/

Visibly invisible marginalisation in Japan

(1960s-1980s)

Modern marginalisation was not in your face; it was hidden behind arbitrary rules and prejudicial language. Korean immigrants were forced to take Japanese names and hide their Korean identity. Noa, in the book, succumbed to the pressure and completely rejected his Korean identity, internalising the shame. Noa previously believed that education would free him from shame and discrimination. After meeting his mother again after 16 years, Noa, overwhelmed by the fear of being exposed as Hansu’s son and as a Korean, takes his own life. However, this shame did not begin once he found out he was Hansu’s son or later in life; it took shape much earlier, within the school system that claims to offer equality but reinforced exclusion.

“Like all the other Korean children at the local school, Noa was taunted and pushed

around, but now that his clean-looking clothes smelled immutably of onions, chilli, garlic, and shrimp paste, the teacher himself made Noa sit in the back of the classroom next to the group of Korean children whose mothers raised pigs in their homes. Everyone at school called the children who lived with pigs buta. Noa, whose tsumei was Nobuo, sat with the buta children and was called “garlic turd.” (Page 164)

Noa had to have two different names to fit into the society. The food one consumed, like kimchi and the smell of garlic that came from its preparation, became a marker of inferiority, racialised evidence. Smell marked the body as permanently foreign. Teachers also participated in furthering marginalisation, not just his classmates. Noa is marginalized through the slow violence of social ridicule and everyday humiliation. Solomon, by contrast, confronts it through formal legal structures and state surveillance.

“They were going to pick up Solomon at his school to take him to get his alien registration card. Koreans born in Japan after 1952 had to report to their local ward office on their fourteenth birthday to request permission to stay in Japan. Every three years, Solomon would have to do this, unless he left Japan for good.” (Page 377)

Having to give fingerprints symbolises criminalisation of his existence, state surveillance and conditional belonging. Even though he was born in Japan, his father was also born in Japan, and he could be deported at any time.

“We can be deported. We have no motherland.” (Page 382)

Together, Noa and Solomon reveal how discrimination evolved without ever disappearing.

Korean women faced patriarchal control, economic vulnerability through dependence on their male partners or male family members and were also subjected to sexual exploitation. Sunja’s choices were shaped by respectability, survival and her kids.

Japan’s economic boom created an illusion of equality and acceptance when, in reality, discrimination became more subtle and bureaucratic. Corporate, housing, and marriage barriers continued to persist. Solomon being fired from his bank job because of his Korean family being involved in a deal reveals the exclusion of immigrants and the historic legacy of marginalisation. Merit failed to overcome racial boundaries time and again for their family.

Japan has repeatedly created a self-image as ethnically homogenous, which continuously erases the diversity and the minorities in its history. Their denial of the prominent discrimination faced by minorities becomes a dangerous, vicious cycle of marginalisation.

Conclusion

Literature makes visible what history often normalises and erases. Pachinko demonstrates how Japan’s marginalisation of minorities did not end with the empire but merely changed its shape. From overt colonial domination to bureaucratic, social, and cultural exclusion in post-war Japan. Pachinko’s multi-generational structure exposes how discrimination adapts to new economic systems and how survival strategies change to combat the hardships in life. Sometimes it takes faith, sometimes silence, and sometimes retaliation and resistance to keep your values. Sunja had to struggle to be alive, Noa had to push through his internalised shame, Mozasu showed resilience on the economic front, and Solomon had to confront corporate exclusion. This progression strictly mirrors Japan’s transition from an empire to a modern-day capitalist mindset. Pachinko helps us understand why discrimination in modern Japan is often denied. It forces recognition of who bears the cost of national myths of unity and progress.

About the author

Apoorva is a second-year student at JGLS majoring in business administration and law. She is an avid reader and artist, actively trying to incorporate creative fields into her everyday work.

Image Source : https://www.minjinlee.com/