By – Aasmi Bali

Abstract

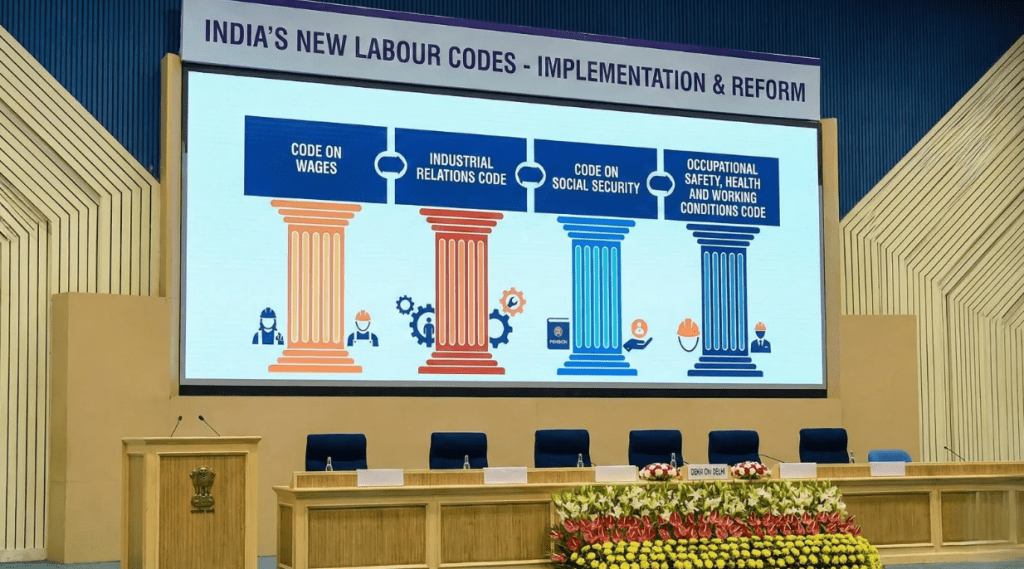

The recent labour law reforms used in India were summarised into four Labour Codes that were launched with the objective to simplify compliance, facilitate ease of doing business, and standardise labour regulation. This article, however, argues that the codification process has also been instrumental in enabling a pronounced centralisation of legislative as well as executive power, which brings into consideration serious federal concerns. Labour, which is constitutionally put in the Concurrent List, has long been used by the States to adjust regulations according to their own socio-economic and manufacturing circumstances. The new Codes, with their sweeping delegations of rule-making authority to the Union, even uniform thresholds and clauses of overriding authority, severely limit State autonomy. The critical question as to whether such centralisation is in line with the constitutional vision of cooperative federalism in India is addressed in this paper. It argues that although there is a good case for harmonisation of labour laws, excessive centralisation would jeopardise democratic decentralisation, State-based innovation, and even efficient labour protection, especially in various regional and informal labour markets.

Introduction

The traditional nature of labour regulation in India has been based on the federal system of the country, and both the Union and the States are given powers to legislate on the Concurrent List of the Constitution. This division allowed the States to address region-based realities in industries, the labour market, and social conditions, and work within a national system. However, over time, the regime of labour laws in India has become decentralised with many central and state laws, which have been accused of being complex and having overlapping regulations. The Union, in turn, responded with a vigorous codification exercise, bringing together twenty-nine central labour laws into four overall Labour Codes. Although this restructuring has been framed as a reform to simplify and be efficient, there are deeper constitutional aspects to this restructuring. The paper places the Labour Codes in the context of the wider debate on federalism and the question of whether the movement towards uniformity and centralisation is weakening the balance that is envisioned in the Indian model of cooperative federalism.

Codification and the Shift towards Central Control

The transformation of the labour laws into four major Codes is a critical move towards altering the present regulatory strategy in India, which is based on decentralised plurality, to centralised uniformity. Although consolidation minimises legislative clutter, the labour codes greatly increase the powers of the Union by highly delegating power to make regulations, and have uniform definitions that can be used throughout the States. Policies that permit the Central Government to inform thresholds, exemptions, and conditions of employment permit policy-making without parliamentary review or agreement by the State. In addition, there is also an overriding clause to guarantee the pre-emption of the central norms over the conflicting State laws, and these can only be limited in their reach to experimentalism at the regional level. This is a structural design, which represents a desire to have national economic coherence rather than federal diversity. As a result, codification is not only a simplification exercise but also a substantive procedure by which the legislative authority is re-concentrated to the Centre, which distorts the traditional balance of the federal system in the labour governance.

Erosion of State Autonomy under the Labour Codes

The Labour Codes substantively weaken the State autonomy in three different levels, such as legislative, administrative, and policy autonomy, thus rebalancing the federal balance of power regarding labour regulation towards the Centre.

First, the autonomy of States on the legislative level is limited by the standardisation of the substantive labour norms. The centrality of the definition of the term wages and the prescription of national wage floors restrict the capacity of the States to adopt labour standards that accommodate regional differences in the cost of living, sectoral structure, and labour structure. States previously had a lot of freedom to shape their minimum wage models and the conditions associated with them; the Codes limit this to common statutory norms, which leave less room for States can make their own.

Second, the reorganization of enforcement and regulation systems undermines administrative autonomy. Making the requirements of standing orders and retrenchments stricter narrows down the regulatory maneuvering that the State labour departments customarily used to shield employees in smaller businesses. Moreover, the move towards technology-based, centrally organised inspection mechanisms, as part of the Codes, limits the discretion of local labour authorities in their priorities in inspections, how to respond to regional industrial practices, and how to deal with violations on the ground. This enforcement architecture centralization reduces the role of the States as regulators.

Third, the freedom of policy-making, i.e., the ability of the States to innovate, experiment, or shape labour welfare structures, is seriously compromised. The unification and centralisation of the social security schemes under the Codes puts the policy design and norms creation in the domain of the national level, and the States are essentially restricted to the implementation roles. This minimizes the chances of the States having their own or additional models of labour protection that are local in the economic and social contexts.

Combined, these changes make States no longer autonomous in regulating labour and turn them into implementing agencies of centrally determined labour policy. This kind of result begs serious questions of the constitutional commitments of cooperative federalism and undermines the capacity of States to respond well to various and region-specific labour realities.

Implications for Workers and Regional Labour Markets

The labour codes with their centralisation provide serious implications to the workers, especially in the diverse and largely informal labour markets in India. Equalised thresholds and standardised employment standards can lead to a disproportionate impact on States with greater informality, agrarian workforce, or small-scale industries, where flexibility in regulation has played a highly important role in the past. Less State discretion may undermine locally specific welfare policies and labour protections, particularly of migrant workers, gig workers, and unorganised sector workers. Additionally, the increased compliance levels under the industrial relations law can restrict the collective bargaining and the grievance redressal avenue of the smaller establishments. The Codes have the effect of marginalising the regional labour realities by focusing on national uniformity and reforms favourable to investments. This also casts doubt on the fact that centralised codification can actually undermine instead of enhancing substantive labour protection in diverse economic and social contexts.

Conclusion

The codification of the labour laws in India is a great structural amendment with far-reaching constitutional consequences. As much as the goal of simplification and regulatory coherence is valid and needed, the Labour Codes show the evident tendency of shifting towards centralisation, which disrupts the federal equilibrium as the Constitution was meant to be. The Codes threaten to destroy cooperative federalism and regional responsiveness by limiting State legislative discretion and increasing the power of the Union via delegated legislation. This essay claims that homogeneity should not be achieved at the expense of State autonomy and the protection of workers. It is necessary to have a recalibrated strategy, i.e, one that accommodates the innovation by States within the harmonised national framework so that labour law reform can be constitutionally sound, democratically answerable, and responsive to the multi-faceted labour realities in India.

Author’s Bio:

Aasmi Bali is a second-year law student currently pursuing B.Com L.L.B(Hons.) from Jindal Global Law School, Sonipat. Her interests lie in technology law, public policy, and digital rights.

Image Source : https://www.prameyanews.com/centre-notifies-4-major-labour-code-reforms-to-boost-manufacturing-and-create-jobs-across-india