By – Tanishka Shah

Abstract

The history of witchcraft in colonial India is not merely a record of superstition and savagery, as British officials often portrayed it. It is a layered history of gendered violence, cultural misunderstanding, and epistemic domination. The figure of the witch was not simply an embodiment of rural superstition but a site where competing orders of knowledge (indigenous, patriarchal, and colonial) converged and collided. This article examines how the belief in the occult, mediated through ideas of witchcraft, became a language through which gender, superstition, and violence intersected, shaping both colonial governance and Adivasi life in the nineteenth century.

Introduction

In the 1850s, in a village in Rajasthan, a man named Koobla, who worked under the Thakur of Edur, fell ill and died. Koobla’s brother, desperate for an explanation, sought answers from a male Brahmin ‘witch-hunter’- a figure who held the authority to confirm supernatural wrongdoing. The verdict was swift, Koobla’s death was Ellula’s doing and a gathering of village officials concluded she was guilty. After having agreed to distribute her possessions and properties amongst themselves, a mob of villagers stormed into Eullal’s home. They dragged her out, tied her hands, burned her eyes with chili paste, and bandaged them so she could no longer cast spells. Unfortunately, she survived this ordeal. At 6 pm, she was tied to a tree and swung violently as the crowd watched. By 9 pm she was dead. The brother and other villagers were set free as the Raja of Edur fined them 25 rupees each.

Ellula’s story is more than a tragic footnote in colonial archives. (It is also not the only one. For more, read this.) It reveals the entanglement of gender, superstition, and violence in the moral worlds of both Adivasi society and British colonial governance.

At the onset, some definitions are sought to be clarified. Scholars like Rodney Needham and Ronald Hutton have defined witches as individuals who use mystical or non-physical means to harm others. Similarly, Keith Thomas links witchcraft to acts that provoke widespread disapproval. However, in this article, it is chosen to be approached as a belief system rather than an objective reality. What truly matters is not whether witches exist but how the belief in their existence influences society. Historical and anthropological studies show that witchcraft accusations often emerge in times of social stress, functioning as a way to explain misfortune, reinforce power structures, and justify persecution. The belief in witches creates its own reality, legitimizing witch hunts and societal control. Thus, in this article, a witch is a person who is perceived to cause harm by supernatural means. Similarly, witchcraft is the presumed employment of supernatural means of doing harm to other people in a way that was generally disapproved of by society.

Background

India has a long history of witch-hunting in the medieval age, but proof and confirmation of witch hunting in India were not documented till the 16th century. The first recorded proof of witch-hunting in India was the Santhal witch prosecution in 1792. In the district Singhbhum, hugely populated with tribals and Adivasis, locally known as the Santhals, the presence of sorceresses and witches were the most common beliefs. People thought that these witches had enough power to destroy humans and animals. Consequently, to cure sickness and diseases, Adivasis concluded that eradication of witches would do the deed by removing the evil eye. Patriarchy forms a significant factor in promoting this kind of abhorrent and vindictive violence. The most common victims of witchcraft accusations were old, widowed, Dalit, poor, or differently abled women. It’s due to the absence of a ‘high’ caste status, youth, or a husband to shield the women, that the women became vulnerable to being branded a witch. They even internalised this patriarchal guilt. Valentine Ball’s Tribal and Peasant Life in Nineteenth-Century India (1880) noted that among Adivasis, “even those who are accused of being witches or sorcerers do not deny the impeachment, but accept the position readily with all its pains and penalties.” The woman’s body became the vessel through which collective anxieties were exorcised. Among the Bhils of Mewar and the Dangs, ‘swingings’ and ritual killings of women accused as dakans were considered not arbitrary cruelty but a form of moral rightness. Violence, Ajay Skaria argues, was seen as necessary to restore cosmic order when women were thought to have unleashed gratuitous harm. British officials, perceiving these rituals through their own lens of legality and civilization, banned such practices.

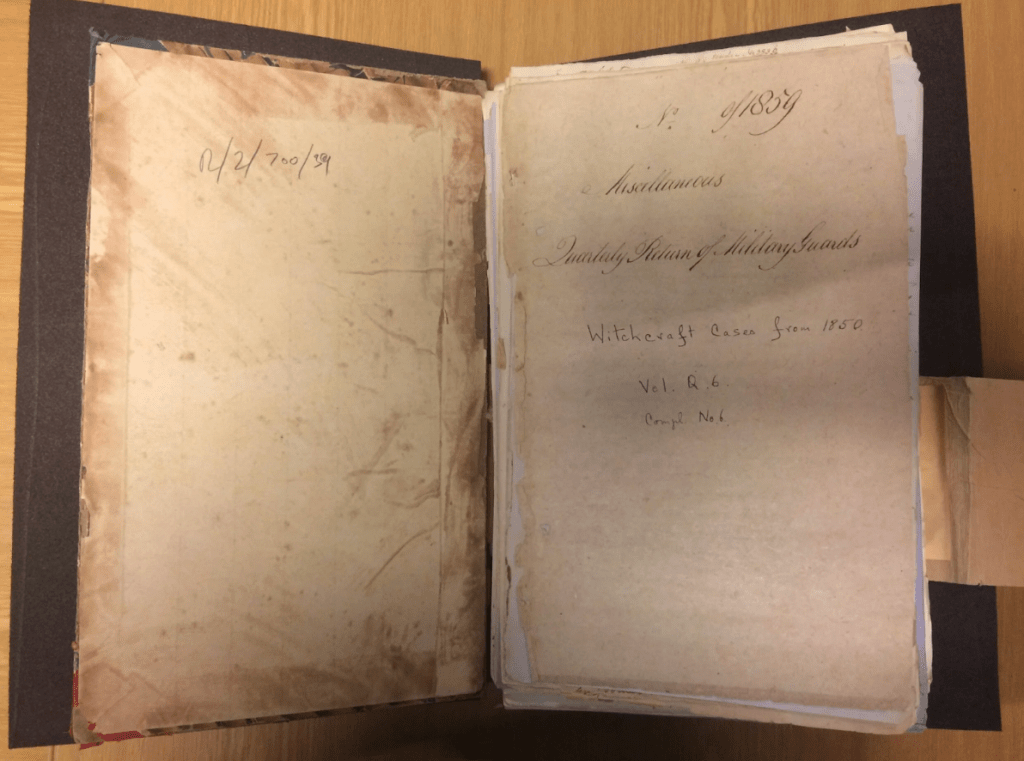

Colonial Narrative and Effect of Bans

Image Source – Lurka Cole, Aboriginal (Fighting Cole), Chota Nagpoor – c1860’s

When William Dunbar in 1861 wrote that witch-hunting among the “Lurka Coles” was “so common among all savage nations,” he actually reflected the epistemological arrogance of British ethnography. Dunbar’s essay, published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, positioned witchcraft as proof of tribal backwardness and a justification for “civilization.” The Coles, he wrote, must “gradually be weaned from their savage and predatory pursuits,” for only then could “the blessings of civilization” take root. This language of savagery and redemption transformed local practices (I acknowledge their violent and complex nature) into moral exhibits of why the empire was necessary. The British civilizing mission, therefore, sought to reform tribal customs by imposing bans on witch-hunting. However, these interventions were often misguided and superficial.

Writing half a century after Dunbar, William Crooke in The Popular Religion and Folk-Lore of Northern India (1896) chronicled “the sad history” of witchcraft in India, noting how British law had “almost entirely suppressed” the “horrible outrages” that native rulers tolerated. His narrative hinted at the irrational ‘past’ of superstition now displaced by the rational ‘present’ of empire. However, Crooke’s own descriptions reveal that witchcraft beliefs persisted “among the lower and less advanced races” such as “Kols, Kharwârs, and Cheros,” who practiced “extreme reticence” on the subject.

To prohibit such acts by law seemed profoundly wrong and crippling to many Adivasis, since it restricted their customary modes of redress. The tribes of Chhotanagpur resisted colonial interference (Kol Rebellion (1831-32) and the Munda Rebellion (Ulgulan, 1895-1900)) and the rise in witch-hunting thus became not only an expression of patriarchal power but also an act of anti-colonial resistance. Statistical evidence reflects the spike in witch-hunting during the 1857 rebellion. The British had failed to grasp the cultural logic of Adivasi societies and their attempts to suppress witch-hunting by punishing ‘Bhopas’ (witch-finders) had only pushed the practice underground. Local chiefs continued to sanction witch-killings, believing it their duty to protect their community from evil forces.

“Oh kill the witch, such the poison,

O kill, kill

O Father, kill the Europeans, the other castes

O kill, kill!”

-songs of Birsa Munda’s great revolt Ulgulan

By the early 19th century, it was estimated that in the plains of central India alone, over a thousand women had been killed as witches within thirty years, more than those who died as satis.

Image Source : Death of a woman said to have been sacrificed for practicing witchcraft

The late 19th century brought profound transformations to Adivasi life. Skaria notes, Bhils were compelled to abandon raiding, adopt settled agriculture, and submit to the regulations of the colonial Forest Department. The result was a double alienation: from land, and from indigenous cosmologies that once gave meaning to misfortune.

A British officer observed in 1875 that Bhil sepoys “say it is of little use” to worship their local goddess since “the power of the goddess has failed since British influence became supreme.” The ‘strong English Gods,’ as the Bhils called them, had eclipsed their deities. This religious disorientation coincided with increased witchcraft accusations. When the old gods seemed powerless and new gods alien, misfortune once again demanded explanation, and the witch became its bearer. Witch-hunting thus emerged as both symptom and resistance; a way of reasserting communal order against the disruptions of colonialism and Brahmanization.

Conclusion

The witch in colonial India therefore stood at the intersection of multiple regimes of power. For tribal men, she embodied misfortune and disorder; for colonial officials, she symbolized native ignorance; for modern historians, she reveals the convergence of patriarchy, superstition, and empire. Each of these perspectives illuminates and distorts in equal measure.

Gender remained central to all. Witch-hunting was not only the policing of women but the production of masculinity (both tribal and colonial). To ‘civilize’ the Adivasi man was to domesticate his violence, just as to punish the witch was to discipline the unruly woman. The result was a recursive loop of control, in which both witch and witch-killer became subjects of law and anthropology.

Witchcraft in colonial India, thus, was never merely superstition. To read the archives today is to confront the persistence of those binaries. The woman branded a witch was caught between two regimes of the occult: the supernaturalism of her community and the civilizing mysticism of empire. Both sought to purify the world of her ambiguity. In that effort, superstition and reason, magic and law, became indistinguishable forms of power.

About the Author:

Tanishka Shah is a second-year B.A. LL.B. student at Jindal Global Law School. She is particularly drawn to exploring the intersections of law, media, and marginalisation.