By – Nandini Pandey

Abstract

The role of food in our lives is immense, yet often goes unnoticed. It is not merely a daily habit but a source of comfort, livelihood and income for an abundance of people. The food we have from outlets for our enjoyment helps sustain a legacy in each bite that we take. This article looks at this neglected role of food as a saviour for refugees in the context of the Indian partition. By looking at particular stories of Khanchand Ramnani and Kundan Lal Gujral, two stranded migrants, with little to nothing left on moving to India, and their rise to stability through the practice of sharing and serving foods, the article establishes the importance of flavour in not just putting them back on their feet economically, but also supporting them by bringing out the memories of their histories, and serving as a source of relief.

Introduction : A Massive Migration

Every year on the 15th of August, millions of Indians step out in white, green, and saffron for a special day. Televisions are turned on in households to watch exciting parades at the Red Fort. Newspapers excite their audience with cheerful pictures of people dancing with vibrant colours. Schools celebrate with flag hoisting and fun snacks, the day that India achieved independence.

In the joyful and momentous occasion is forgotten another anniversary that the day is infamous for. The wild, disarrayed, traumatic partition of India. The day when Muslims of India were asked to leave their homes, their lands, and their beloved to move into their new country of Pakistan, and the same was done to the Hindus and Sikhs of the new Pakistan. In the span of two days, eighteen million people were displaced. An unawareness regarding the meaning of the partition, and the new boundaries established paved the way for horrific communal violence where each side slaughtered and was slaughtered by the other. Women were abducted, raped, and killed. The violence resulted in the deaths of over 500,000 people. What became of those who survived?

Chandulal and his family were a part of this group. Travelling from Karachi to Mumbai amongst such violence and pain, they still provided aid and relief in the form of food to refugees. Gondalwala, another such victim, was aged thirteen when he was required to move with his family to Bombay from Rajkot. Having lost his father to poverty, the responsibilities of a safe migration, and further rebuilding of life, fell on him. With a single pair of clothes and a single meal a day, this family too arrived in India.

How were they able to rebuild a life in a lost world? What happened to their sense of comfort and home? Were they ever able to revive it? This paper looks at the stories of two survivors : Khanchand Ramnani and Kundan Lal Gujral, to argue how food restored the partition refugees not just in an economical manner, but also at a psychological level. By bringing in its crafting and flavour a piece of heritage so close to home and comfort, food ensured a level of stability in the lives of stranded refugees.

Karachi Bakery : A Sindhi Relic

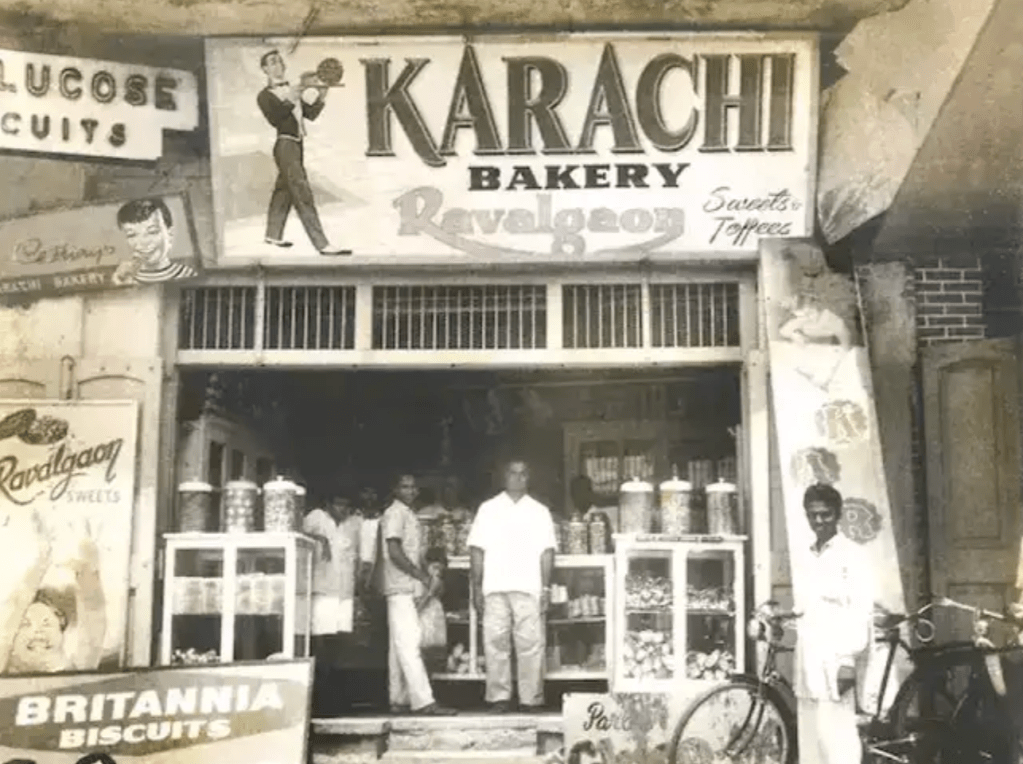

Khanchand Ramnani was running a bakery shop in the city of Karachi (now in Pakistan) when he was forced to leave his life in order to shift to India. Being a Hindu Sindhi, Ramnani’s presence was no longer welcomed in his home, as was decided by the leaders of the time. In the times of havoc and trouble, Ramnani moved along with his four sons to the Indian city of Hyderabad. Having moved to a completely new locality, with nothing to carry with him but clothes, and a special few recipes of his own crafting, in 1953, he still decided to honour his origins, and set up again a bakery, in the Moazzamjahi market of Hyderabad which he named after his dear beloved home and its memories.

This journey was not a simple one for Ramnani. Starting from scratch, he started off his new livelihood by supplying coal to transporters and buying wholesale breads to sell them in his bakery. This continued for years, but when time allowed it, he again began to bake his own bread. It was in the 1960’s that he reintroduced those cherished recipes he had crafted in his home and carried with him during the partition. The bakery soon began to thrive, and was able to open an outlet in the posh area of Banjara Hills of Hyderabad. Over the decades, it found popularity throughout India, expanding its stores and cafes to other major cities.

This is the story of the establishment of the famous and beloved Karachi bakery. The bakery now run by Ramnani’s grandsons stands proud of its history, and is appreciated beyond boundaries for its fruit cookies and Osmania biscuits.By trying to establish a living, Ramnani’s family was able to bring with them a heritage, a history, and a culture that continues to be appreciated by so many. Ramnani did not just establish himself, but also brought a piece of home with him, and shared it with so many others that were stranded like him in this strange land of post-partition. In this process he was able to participate with others in his memories, and renew them once again.

Similar is the story of another such character, who burdened with the same situations of life was yet able to make a name both for himself, and his country, through the simple art of food.

Moti Mahal : Dishes Immortal

Kundan Lal Gujral too was made to abandon his passions in order to join the sea of migration. Residing in Peshawar (now in Pakistan) Gujral was the son of a cloth maker. His interests however, lay in the art of food-making. Till the time of partition, Gujral worked in a catering joint, his passion reflecting in the increasingly well to do joint. However, he, like many others, was required to leave all he had done to move to a new country. Having lost his father as a child, he was made the head of the family, and his instincts led him to travel with his family to the capital city of Delhi, with no more in his hands than his culinary expertise and love for food.

In Delhi, Gujral established a wayside cafe, that was to grow to become the ‘Moti Mahal’ we know today. Starting from this small entity on yet another Delhi street, Gujral was able to build up the brand name that is responsible for inventing the butter chicken. Here is where the recipes considered world class were laid down by Gujral himself, gaining immense popularity not just within Delhi, or India, but becoming a signature Indian dish across the world.

It was solely the craftsmanship of Gujral and the aromas his skills created that led his passions to reach such lengths. His commitment to his love for catering took him from a roadside eatery, to eventually cater for the Prime Minister’s meetings. A refugee with a family to protect was able to make himself a name which has now become staple to India. His story was evidence of how although partition divided lands and people, it could not divide memories, histories, and love. Gujral may have had to leave behind his home in Peshawar, but the partition could not induce to leave behind his souvenirs, his love for catering, and his natural skills for the art, and in their comfort he could find a new living. Moti Mahal’s continuance is a reminder of this very truth.

From Comfort to Saviour

In the case of both Gujral and Ramnani, food exceeded the role of a comforter to act as a saviour. The refugee families could not carry their beds, homes, trees, or sunsets on their back, but their daily craftsmanship was to always remain with them. In carrying such comforting familiarity in its taste, food ensured an economical revival through a personal one. Their act of food sharing was further a source of providing a taste of their home cities to all others newly referred to the country of India.

Elsewhere too, the feeling of homeliness has been able to revive amongst refugees through the act of sharing and having nostalgic food. Food is the one entity that embalms in its flavours generations of heritage, culture, and histories. Each flavour induces emotion and moves the heart. Thus, it was bound to affect those who were helpless and lost. By ensuring a feeling of reassurance it could bring in them the confidence of survival.

Such stories find a continuance in India not only through the popular brands of Gujral and Ramnani, but through numbers of eateries and sweet shops across the streets of India. Chandulal and Gondalwala, mentioned earlier in this paper are examples of this. Both struggled in vain after partition and eventually established their eateries. The former introduced to India the famous ‘Karachi Halwa’ while the latter started the ‘Noor Bakery’. The histories of both these refugees are preserved in their eateries carried on by their families.

Conclusion

Such stories remind us not only to admire food more, but also ask us to admire the ones who make it. Whether it be the food we eat at home, or the outlets we go to, it is worth knowing where each flavour comes from. A curiosity in what we consume daily, yet so indifferently, will perhaps help us understand a person, and their past, or even ourselves, and our own past, in a manner we never could.

The stories of the four families in this paper are themselves telling of forgotten histories. Each story is telling of the different kinds of problems every individual faced in those dark times, whether it be poverty, loss of family, or destitution. However, each of these individuals were able to cope with these struggles, along with the settings of a new life in a manner both unimaginable and admirable with the support of a feeling of solace. Each in their own way brought in a culture that was new to the country, but a sense of home for them. These stories are proof of the power we carry within us through the little things that make our identity, in this case that little something being as simple as food.

About the Author

Nandini Pandey is a second year student at O.P. Jindal Global University pursuing a bachelors in Law.