By:- Tanishka Shah

Abstract

While Partition is conventionally narrated as a conflict of religions, for Dalit Namasudra refugees it was equally a story of caste marginalisation. From their pre-partition mobilisation and Jogendranath Mandal’s alliance with Muslims, to their subsequent displacement, relocation to Dandakaranya, and the violence of the Marichjhapi massacre in 1979, the Namasudra trajectory reveals how caste was systematically erased from Partition histories.

Introduction

The Namasudras were a community based in Bengal, traditionally associated with fishing and boatmanship, before many transitioned to cultivation. They were historically regarded as “untouchable” within the Hindu caste hierarchy. By the early 20th century the community consolidated under the Namasudra movement, which sought to eliminate intra-community distinctions and forge lateral solidarity in resistance to uccho-borgiyo (dominant-caste Hindu) landlords and zamindars.

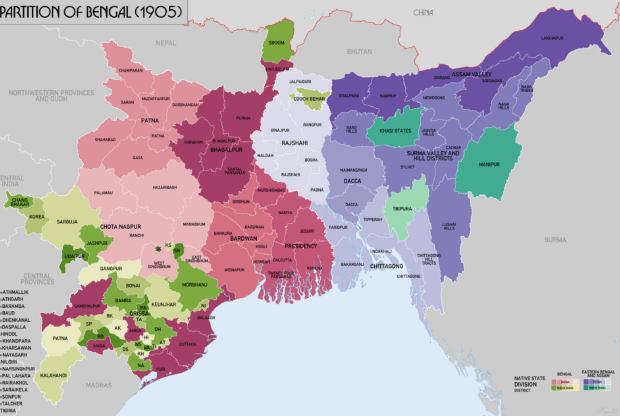

When the British government sanctioned the partition of Bengal in 1905 along religious lines, the Namasudras endorsed the proposal, as their grievances found common ground with Muslims, as both communities saw their marginalisation stemming largely from the dominant-caste Hindus in Bengal’s social and political order. This early alignment foreshadowed the political choices the community would make during the Partition of 1947.

Namasudras chose to opt out of Swadeshi movements because they perceived it as a movement that benefitted the dominant-caste and their interests. In response, Swadeshi leaders launched extensive campaigns in Namasudra areas, attempting to win support through persuasion, incentives, and, at times, coercion. Bandyopadhyay argues that such gestures were primarily instrumental and the goal was not genuine reform but to ensure that oppressed castes identified as “Hindus,” thereby boosting Hindu demographic strength in provincial redistribution debates. People like Guruchand steadfastly refused to back a movement that showed little commitment to social reform. . By the late 1930s, particularly after the Poona Pact, the Namasudras increasingly adopted a loyalist stance toward the British, viewing colonial patronage as their best chance at socio-economic advancement. The 1941 Census, which classified Namasudras as Hindus rather than as a distinct community, left many feeling deceived.

The Immediate Aftermath of 1947

In 1947, the Namasudras’ caste identity complicated their choices. Having been political allies of Muslims, many Namasudras chose to remain in East Pakistan, believing they would be protected. Jogendranath Mandal, a leading Namasudra figure, lent his support to the Muslim League and became one of the 96 founding members of the Dominion of Pakistan. For his loyalty, Jinnah rewarded Mandal by appointing him Pakistan’s first Law and Labour Minister.

However, after Jinnah’s death in 1948, Dalits and Hindus in Pakistan faced mounting hostility. Bandyopadhyay observes that they were quickly subjected to “a process of ‘Othering’” as the state pursued “greater Islamisation of the polity.” Mandal himself was humiliated by the bureaucracy, eventually resigning and returning to Calcutta. In Pakistan, the projected ‘Other’ of the nation was the undifferentiated category of the ‘Hindu,’ which collapsed distinctions among non-Muslims and subsumed Dalits within it. This simultaneously excluded Dalits from the imagination of Pakistani nationhood and, paradoxically, enabled Hindu nationalism in India to appropriate them as an oppressed Hindu minority.

In December 1949, an incident in Kalshira village of Bagerhat subdivision, Khulna, marked a turning point. When villagers resisted a police search for communists, resulting in the death of a constable, security forces retaliated by attacking Kalshira and 22 neighbouring Namasudra villages. The Calcutta press framed the victims simply as ‘Hindus,’ erasing their identity as communists and Dalits. This provoked riots in Calcutta and Howrah which in turn triggered retaliatory violence across East Pakistan. The chief victims were not the dominant-caste bhadralok (most of whom had already migrated), but Dalit and tribal peasants such as the Namasudras and Santhals, who were now compelled to abandon their homes and cross into India. This episode symbolised the rupture of the fragile Dalit–Muslim alliance in East Pakistan.

Beginning in early 1950, Namasudra peasants migrated en masse to India, a movement that continued until 1956, averaging roughly 10,000 arrivals per month. By the beginning of 1951, following the disturbances in Khulna, about 1.5 million refugees had arrived in West Bengal, majority being the Scheduled Caste peasants. By mid-1952, a police intelligence report estimated that “about 95 per cent of the refugees are Namasudras,” underscoring their disproportionate share in the refugee crisis. This number was 2.1 million by the end of 1956. Retaliatory communal violence on both sides of the border accelerated this flow, which was later reignited by the Hazratbal riots of 1964.

This exodus forced by communal targeting, economic exclusion, humiliation, and violence is telling that Partition was not a single event in 1947 but was an ongoing catastrophe stretching across decades. For the Namasudras, its most haunting legacy was the profound sense of belonging nowhere. They were at home in neither Pakistan nor India, and were reduced instead to a statistic, and a bargaining tool. It is this condition of displacement without belonging that I aim to foreground in this article. In what follows, I will trace the horrors of Partition as experienced by the Namasudras upon their return to India.

The Deferred Horror of Partition

The arrival of Namasudra refugees in India after Partition did not mark an end to their suffering. Instead, they were confronted with new forms of exclusion, this time within the borders of the nation they had chosen for refuge. While dominant-caste refugees were able to settle in Calcutta and its surrounding districts, often occupying properties vacated by departing Muslims or benefiting from government housing, Dalit refugees like the Namasudras were denied such opportunities. Their caste location rendered them less “desirable.” Apart from this, the dominant-caste refugees who had illegally occupied large areas in and around Kolkata and other major cities of Bengal, got it regularized but when it came to Dalit refugees, the then Congress Chief Minister B.C. Roy wrote to Prime Minister Nehru that ‘we have no place for them, send them to other states’.

Uditi Sen notes that while the government treated bhadralok refugees as “citizens displaced by Partition,” Dalit refugees were framed as “burdensome populations” to be removed from Bengal altogether. Under the Dandakaranya Development Scheme, tens of thousands of Namasudras were relocated to remote and inhospitable forests in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Odisha. Relief, rationing, and housing allotments were more readily available to dominant-caste refugees, who also drew on networks of kinship and education to secure jobs in Calcutta. Namasudras, by contrast, in overcrowded camps, were left with little access to schools, health facilities, or pathways to economic stability. Their designation as “Hindu refugees” in official discourse erased caste distinctions rhetorically, but in practice caste shaped every dimension of their treatment. Namasudras were instrumentalised but not integrated.

Refugees from East Pakistan at Dandakaranya

By the late 1970s, political shifts rekindled Dalit hopes. The Communist Party of India (Marxist) [CPI(M)], then in opposition, had vocally demanded rehabilitation of East Bengali refugees in West Bengal, with the Sundarbans suggested as a possible site. Encouraged, many Namasudras left Dandakaranya and settled on Marichjhapi island in the Sundarbans, renaming it Netaji Nagar. In 1979, however, the CPI(M)-led Left Front government reversed its stance. Chief Minister Jyoti Basu authorized an economic blockade to starve out the refugees. Relief agencies like the Bharat Sevashram Sangha and Ramakrishna Mission were expelled.

Accounts from survivors describe poisoned wells, deliberate ramming of refugee boats, and sexual violence against women. On 14 May 1979, the state launched a full-scale eviction. Police torched schools, hospitals, and markets. Hundreds were shot, drowned, or burned alive. Eyewitnesses reported bodies dumped in tiger reserves and the Bay of Bengal. Estimates suggest up to 1,700 deaths, including women and children. Survivors were forcibly returned to Dandakaranya. Estimates also indicate that nearly three-fourths of the refugee settlement was wiped out, making Marichjhapi not only a massacre but also a profound betrayal.

Conclusion

To remember Partition without caste is to leave unspoken the silencing of Dalit voices, whose histories of displacement and dispossession remain at the margins of both nations’ memories. The Namasudra experience has renewed relevance in light of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) 2019 and the National Register of Citizens (NRC). The CAA frames “persecuted Hindus” as beneficiaries of Indian citizenship, erasing the caste dimensions of refugee identity. For Dalit refugees like the Namasudras, “Hinduness” has historically not guaranteed dignity or inclusion. Their loyalty, first to the Muslim League, then to the CPI(M), and now invoked by Hindutva politics, has repeatedly been betrayed. The “Hindu dividend” benefited them only in comparison to Muslims, but within Hindu society they remained expendable. Marichjhapi is a stark reminder that caste cannot be dissolved into religion, and the refugee question in Bengal has always also been one of caste.

About the Author:

Tanishka Shah is a second-year B.A. LL.B. student at Jindal Global Law School. Her research interests lie in the intersections of media, law, and marginalisation.

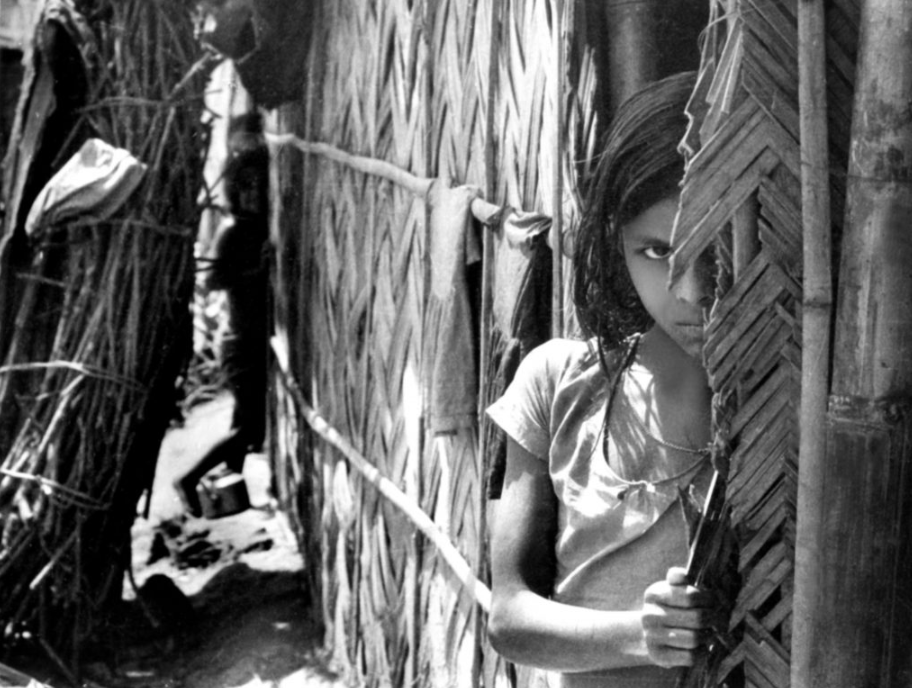

Image Source : Photograph from Marichjhapi Massacre