By – Tanishka Shah

Abstract

This paper tries to reconstruct the economic contributions of women in early modern India, centering labour that has long remained peripheral in official accounts and mainstream historiography. It argues that women were indispensable actors in India’s agrarian, artisanal, and proto-industrial economies. From spinning cotton for a thriving textile export industry to engaging in rice cultivation, food processing, mat weaving, pottery, and small-scale market trade, women’s labour was both ubiquitous and systematically undervalued. In particular, the paper traces how women’s domestic and informal labour underwrote India’s position in early modern global trade networks. It calls for a methodological reorientation that takes seriously the dispersed, embodied, and household-based labour of women as foundational to India’s economic history.

Introduction

History has often been shaped by the hands that held the pen. As written language evolved into a dominant medium for recording the past, it also centralised power. Written history, especially economic history, was, as a result, predominantly shaped by elite male voices, particularly in literate and state-centred societies. Those who learned to write could dictate which stories were told, remembered, and repeated. That is not to say that this history should be outright discredited. Nevertheless, in engaging with it, we must understand that these are not the only voices, nor necessarily the most important. It’s crucial, therefore, that the history is continually re-examined through a critical lens, to identify gaps within the story and allow space for revisions backed by evidence that broaden our understanding of the past beyond an exclusively masculine, elite perspective.

This piece aims to revisit one such neglected landscape: early-modern India, often celebrated and prided as the world’s leading economic power before European imperialism took hold. By the 18th century, India contributed nearly a quarter of the world’s industrial output. But one must ask: where were the women in this prosperity? What were their contributions, and why do they remain largely unseen in our economic history? We must recognise that the absence (rather erasure) of women in this history is not the same as non-participation. Revisiting these silences is not about retroactively inserting women into a story where they had no place, nor is it to claim that they were the central drivers of this economic surge, but rather it is about recognising that the story itself has been somewhat narrowly framed. Only by acknowledging the biases in our sources and frameworks can we begin to reconstruct a fuller, more inclusive account of the past.

While the rise of pre-colonial India’s economic strength is often measured through trade records, guild activity, and imperial accounts, a significant share of its prosperity was quietly powered by women, especially through agriculture and textile production, the two largest engines of the economy. These contributions, however, remain underrepresented in dominant economic narratives.

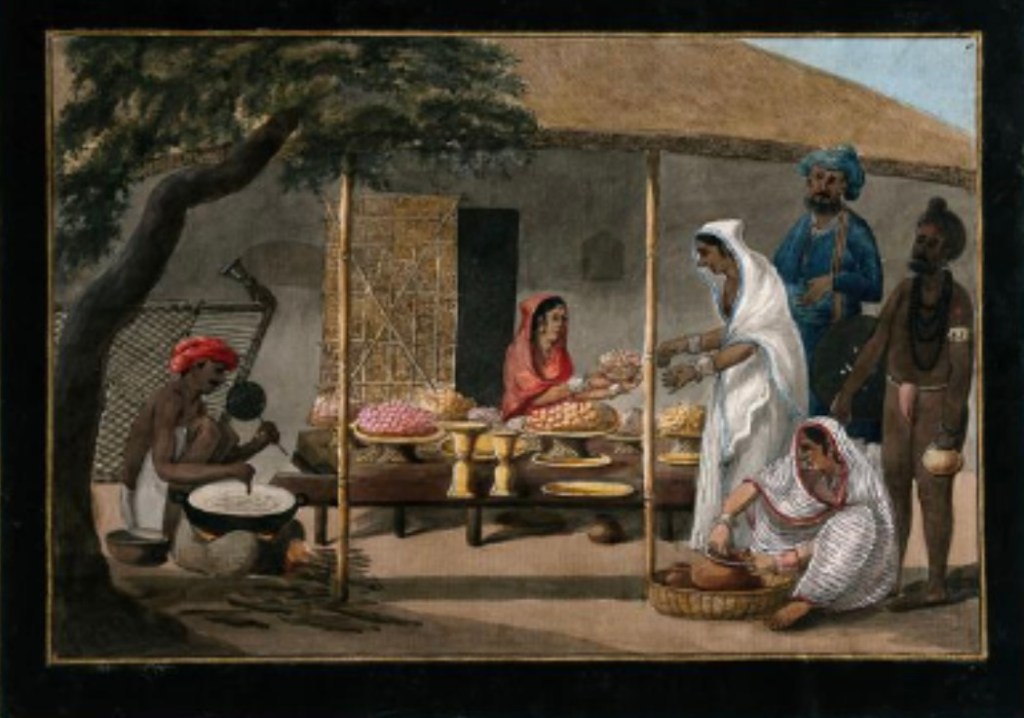

Image source: https://www.alamy.com/india-a-pastry-cooks-shop-between-1800-and-1899-image682392052.html

Women in the Fields: The Invisible Backbone of Agrarian India

Across much of precolonial and early colonial India, women played a crucial yet often overlooked role in agrarian production. They joined men in sowing, weeding, harvesting, and post-harvest processing. Colonial reports on Bengal note that pounding, husking and parching grain were handled almost exclusively by women. In eastern Mysore, women worked the fields, carried manure on their heads, and contributed to the entire crop cycle. Corn was threshed mainly by women using their hands, as there was usually no organized corn threshing industry in the sixteenth century. Rice processing was in fact “naturally… the women’s lot.”

In Dinajpur, women operated the dhenki (a six-foot wooden lever) to process rice. In Behar, women earned 2 to 4 paisas per day (such numbers, while valuable, often stem from colonial enumeration logic with their own blind spots), often matching men’s wages when transplanting or weeding rice. In Priya-Pattan, they cultivated sugarcane, poppy, and vegetables in both wet and dry lands, underscoring their wide agroecological engagement. Farm labourers earned from £1 to £1, 7s. a year besides one meal a day; and women labourers earned 6s. a year besides two meals a day. In Colar, farm servants (including women) received around 29.25 bushels of grain and 13s.5d annually, while day labourers received 3d for men and 2d for women.

In drought-prone or frontier areas, women would even clear fields or plant crops when men were absent. A striking case is 16th-18th-century Manipur when forced male labor drafts (lallup-kaba) led to the emergence of Imphal’s “Ima Keithel” (Women’s Market). The royal chronicle records that Manipuri women had to support households by cultivating their fields or weaving textiles and then selling the products. (Ima Keithel remains the world’s only all-women market, with thousands of vendors today.) This economic independence was born of necessity, but it carved out public and financial spaces for women.

British administrators occasionally acknowledged the autonomy embedded in women’s roles. Thomas Munro observed in the early 19th century that Indian women were not passive subordinates in family economies. When asked if Hindu women were not slaves to their husbands, he replied, “they have as much influence in their families as, I imagine, the women have in this country [England],” hinting at the decision-making power and autonomy many exercised within the household and community. Taken together, these accounts suggest women’s invisible but extensive role in food production, from the plow to post-harvest processing, which sustained local economies across India.

Yet agricultural labour was only part of the picture. Just as critical, and unfortunately just as invisible, was the role of women in textile production, a cornerstone of India’s export economy.

Image Source: https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-two-women-with-a-curry-stone-and-a-raggy-mill-at-madras-in-1870-143453943.html

Threads of Labour: Women in the Textile Industry

Between the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries, India’s textile industry made it one of the key centres of the then-emerging world economy. In the 1700s, India held 25% of the global textile trade. Dr. Francis Buchanan’s surveys during the late 18th and early 19th centuries (though commissioned by colonial authorities) offer a valuable window into the scale and significance of women’s labour. In regions like Eastern Mysore, spinning was a ubiquitous household occupation: women across castes purchased raw cotton, spun it at home using the charkha, and sold the yarn to local weavers. In Behar district alone, Buchanan recorded over 330,000 women engaged in spinning, producing yarn worth over Rs. 2.3 million annually and generating a collective profit of more than Rs. 1 million. While each woman earned only about Rs. 3.5 per year, this supplemental income played a critical role in sustaining household economies. Similar trends were documented across northern India, in Shahabad, around 159,500 women were involved in spinning. In Bhagalpur, over 160,000 women from various castes participated while in Gorakhpur, about 175,600 women found employment in spinning. Earnings ranged from Rs. 2.5 to Rs. 4.5 per year. This shows not only the volume of labour, but also its invisibilisation through wage-based economic frameworks. Moreover, spinning was not confined to the poor or landless; Buchanan noted that even “women of higher rank and the greater part of farmers’ wives” took up spinning during leisure hours, emphasizing its normalization across class lines.

Women’s contributions extended beyond spinning. The flowering cotton cloth with the needle gave a good deal of occupation to the Mahomedan women of Malda. The flowers were either Kosida having running patterns, or Chikon having detached flowers or spots. Some Mahomedan women also made silk strings for tying trousers or necklaces or bracelets. Block-printing and dyeing also engaged women. In colonial Calcutta, for instance, women painstakingly carved or patterned printing blocks for calico cloth. Many households had looms, and women often worked in the afternoons while managing domestic duties.

At its peak, between 1809 and 1813, over 80% of the 12.7% of India’s working population involved in cotton textiles were engaged in spinning. However, this foundation crumbled swiftly under colonial economic reordering. British imports flooded Indian markets with machine-spun yarn and cloth, displacing indigenous production. According to a study cited by Irfan Habib (1985), yarn for handloom production dropped from 419 million pounds in 1850 to 221 million by 1900. The collapse of spinning led to a sharp decline in hand weaving and related livelihoods, disproportionately affecting women who were never formally counted as part of the industrial economy. Buchanan noted that “millions of women eked out the family income by their earnings from spinning.” Colonial rule not only deindustrialized India but entrenched gendered pay disparities. Women were paid a fraction of what men earned for similar tasks, if paid at all. Much of their spinning was done within households, rendering it invisible to wage-based economic metrics. This structural erasure ensured that women’s labour, though foundational to India’s premier export industry, was neither protected nor remembered.

Image Source: https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-vintage-photograph-of-sari-weaving-in-maharashtra-1873-143454059.html

The Uncounted Economy: Women’s Work Within Walls

Women were indispensable to India’s agriculture and textile industries, but their contributions extended far beyond those domains. A substantial share of women’s economic activity took place within the household or community. Women also engaged in a range of subsistence and income-generating tasks like preparing food items for sale (such as breads, sweets, and pickles), brewing toddy, distilling oil or sugar, sewing quilts, and dyeing or washing cloth. Handicrafts such as basketry, mat weaving, pottery, gold-thread embroidery, and tanning were similarly female-intensive and organized around village economies. These forms of small-scale production routinely entered informal markets, blurring the line between domestic labour and economic enterprise. Crucially, even routine domestic responsibilities carried economic significance. Women managed livestock, raised children, and maintained households, freeing up male labour for fieldwork or wage employment. In effect, their unpaid and often invisible labour sustained both family survival and the broader rural economy. It is imperative that accounting for India’s precolonial prosperity thus requires recognizing this hidden workforce.

This piece does not purport to be exhaustive. Much remains undocumented or exists in forms that resist neat categorisation like the labour of Dalit women, peasant women, those from religious minorities, Adivasis, and even dominant-caste household producers. They cannot be fully captured in a single narrative, nor should they be reduced to data points or anecdotal accounts alone. Oral traditions, embodied labour, community memory, and unmonetised work all lie beyond the reach of conventional economic archives.

Still, this is an attempt to question the silences that have long shaped our understanding of prosperity and production. If history has often excluded women because it was written by and for those with access to pen, print, and power, then revisiting that history must involve rethinking the frames themselves. By foregrounding women’s roles in agriculture, textiles, and everyday economies, the hope is to invite a broader, more inclusive conversation about whose history we choose to remember and read, and why.

About the Author:

Tanishka Shah is a second-year B.A. LL.B. student at Jindal Global Law School. She is particularly drawn to exploring the intersections of law, media, and marginalisation.

Image source: https://www.alamy.com/women-grinding-paint-in-calcutta-c-1845-daguerreotype-medium-image152822948.html