By : Aditi Gupta

Abstract:

Conflict-induced food insecurity has severe humanitarian and environmental consequences, affecting millions worldwide. Warfare tactics such as the destruction of agricultural infrastructure, displacement of farmers and contamination of water sources disrupt food production, leading to famine and long-term environmental degradation. This paper explores the intersection of conflict, food security and environmental degradation, using case studies such as the Ethiopian conflict (1986-1989) and the ongoing Israel-Hamas war in Gaza. The destruction of agricultural lands in conflicts has led to severe food shortages, water scarcity and environmental pollution, exacerbating the region’s reliance on humanitarian aid. Furthermore, climate change and economic shocks further intensify food insecurity, often leading to civil unrest and conflict, as seen in sub-Saharan Africa and Somalia. Sustainable agricultural practices, water conservation strategies and food aid interventions are critical to mitigate these challenges. Policies must prioritise environmental restoration and resilience-building efforts to ensure long-term food security and ecological sustainability in conflict-affected regions. This analysis emphasises the urgent need for comprehensive solutions that address both immediate food needs and the long-term environmental consequences of conflict.

Food Insecurity, the Environment and Conflicts

In warfare, it is commonplace to strategically target enemy sources of sustenance by poisoning wells, burning crops, destroying critical infrastructure and displacing people and livestock. This is termed as “starvation campaign”, aimed at causing food insecurity. The 2023 Global Report on Food Crises suggested that conflicts caused acute food insecurity to over 117 million people, exacerbating hunger and malnutrition. The bombing of agricultural lands leaves behind explosive and toxic remnants, rendering fields inaccessible for cultivation, thereby increasing the risk of famine and long-term land degradation. Moreover, disruption in food production- due to the forced displacement of farmers, herders and workers—halts economic activity and accelerates environmental deterioration, such as soil erosion and desertification.

Conflict-affected areas face severe challenges such as deforestation, contamination of water bodies and loss of biodiversity. As productive land is abandoned, invasive species take over and soil fertility declines due to a lack of maintenance and regenerative agricultural practices. In the long term, conflict zones become ecological dead zones, hindering any potential for agricultural revival and self-sustenance.

For instance, between 1986 and 1989 during the Ethiopian conflict, 23,000 hectares of land was rendered unfit for cultivation, resulting in a loss of 65,000 to 95,000 tonnes of annual production. The environmental consequences were severe—soil erosion, water scarcity and deforestation were intensified, leading to habitat destruction and loss of indigenous flora and fauna. Additionally, the collapse of local markets and supply chains led to price surges and restricted access to essential food, further worsening the crisis.

The situation is further exacerbated by the looting and destruction of stored food supplies, aid convoys and transportation infrastructure. Civilians suffer from a lack of access to fresh sources of protein and nutrition, relying primarily on food aid, which consists largely of non-perishable, processed items with limited nutritional value. This not only affects physical health but also leads to long-term developmental challenges for children and vulnerable populations.

The Link Between Food Insecurity and Conflict

While wars cause food insecurity, food insecurity itself can also be a catalyst for conflict. Climate change and economic shocks significantly contribute to food insecurity, triggering cascading effects on social stability. Rising temperatures, erratic rainfall and droughts have led to crop failures and livestock losses, resulting in competition over dwindling resources. These factors can lead to civil wars or domestic unrest as food systems often feel the impact of climate change first, and a hungry population is an angry one.

In sub-Saharan Africa, reduced corn yields led to a rise in civil conflict and this trend is predicted to worsen with the continued warming in the coming decade. Somalia, for example, has witnessed a direct correlation between decreased annual rainfall and a surge in domestic terrorist activities, as diminished water and food resources push populations towards desperation and insurgent groups for survival.

Case Study: Environmental and Food Security Crisis in Gaza during the Israel-Hamas War

The Gaza Strip, historically a fertile region producing crops like cucumbers, tomatoes, dates, olives, strawberries and citrus fruits, has faced significant agricultural devastation due to ongoing conflict. The olive harvests, in particular, are central to Palestinian life and culture as a symbol of their resilience against Israeli occupation. Under the Israeli siege, 68% of agricultural areas have been damaged by conflict and farmers are unable to fertilise or irrigate their lands. About 71% of orchards and other trees, 67% of field crops and 58.5% of vegetable crops have been damaged. Israeli heavy machinery and bulldozers have razed strawberry fields in Beit Lahiya, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions and soil degradation.

Moreover, the destruction of fishing infrastructure at the Port of Gaza City, with most fishing boats destroyed, has crippled the fishing industry, leading to a decline in local protein sources. The bombing of small-scale fishing vessels, greenhouses and olive orchards in Gaza is contributing to carbon emissions. This is a tactical strategy of settler colonialism to deprive Palestinians of food by targeting the Palestinians’ indigenous food systems such as agricultural areas, fishing infrastructure, seaports, and rural areas.

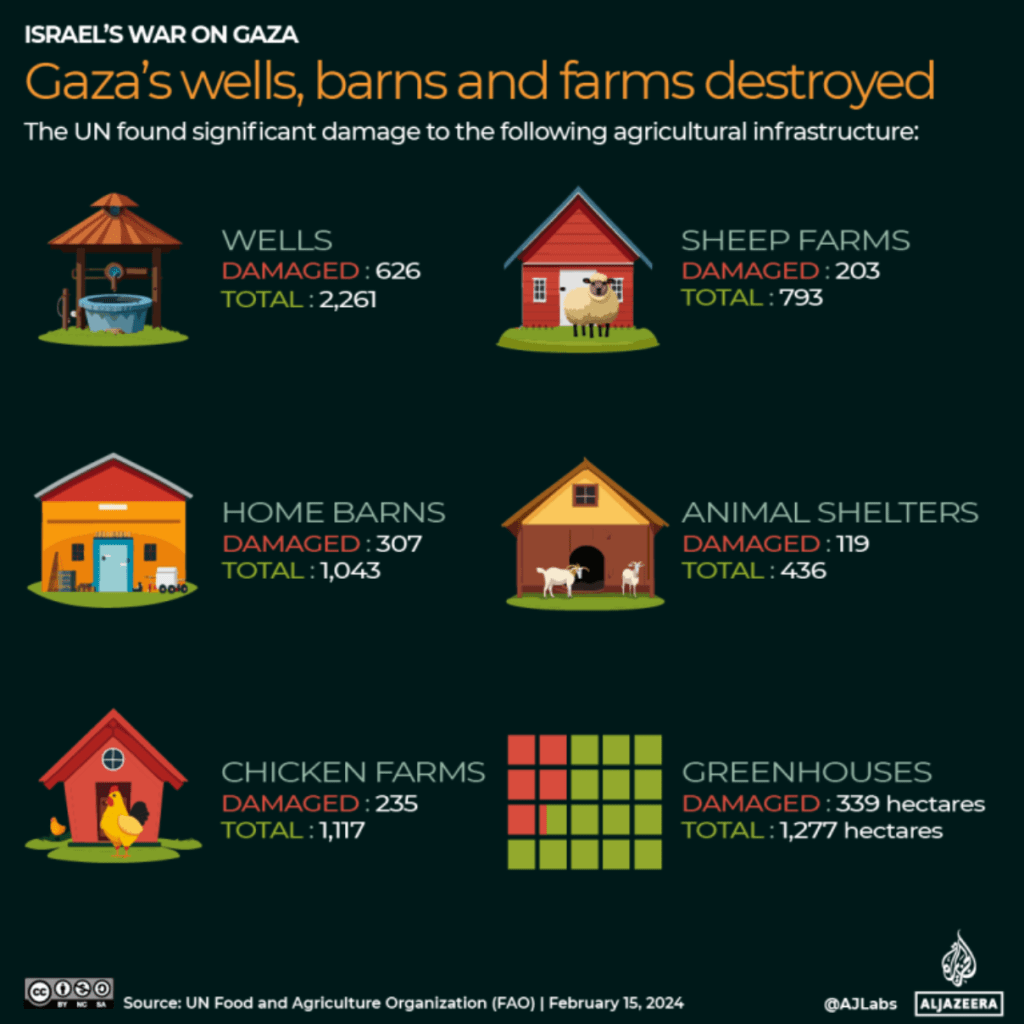

(Image Source : https://www.aljazeera.com/news/longform/2024/7/2/how-israel-destroyed-gazas-ability-to-feed-itself)

These attacks on agriculture and fishing industries undermine self-sufficiency, contributing to rising starvation, disease and dehydration cases. The long-term health consequences of the decline in essential nutrients include malnutrition, bodily deformities, medical complications in pregnancy and premature deaths. This is coupled with an acute shortage of living space, clean and drinkable water and medicine. Cultivating is also currently difficult as water prices shot up where pipelines are functioning. Rates went from 2.5 to 3 shekels before the war to 79 to 90 shekels per hour of running water. The crisis is further enhanced and sped up by the pre-war 16-year blockade which left 80% of Gazans dependent on humanitarian aid. The hardest hit to the population is that they are forced to rely on canned food which lacks essential nutrients. The future generations of Palestinians are prevented from sustaining themselves. The cost of such attacks inevitably impacts the long-term recovery of livelihoods.

Conclusion: Hunger Mitigation Policies and Strategies

To help economies bounce back, coping strategies such as subsistence farming can be undertaken to meet the basic nutritional requirements of the citizens. Consumers must shift dependence towards small grains like millet and sorghum, fruits and carbohydrates like sweet potatoes and groundnuts. Accessible farmland should be utilised for diverse crop cultivation. Rural communities can supplement food sources through hunting and fishing, while urban populations can engage in home gardening or container farming. Interventions must focus on short-term benefits without neglect of the environment, long-term food security and recovery of livelihoods. Policies adopted must promote the protection, preservation and restoration of the natural environment from further degradation. Locally sourcing and purchasing food items must be promoted to revive the economy. Mobilisation of aid from the United Nations must be undertaken such as the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s initiative to provide farmers access to fodder concentrate, greenhouse plastic sheets, water tanks, animal vaccines, veterinary kits and other inputs all critical for restoring their livelihoods and ensuring food security.

Author’s bio

Aditi Gupta is a graduate of B.A. (Hons.) Liberal Arts and Humanities with a major in Political Science and International Relations. She is interested in pursuing further studies in international relations, environment studies and economics.

Image Source : Food and Agriculture Organisation – https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/gaza-geospatial-data-shows-intensifying-damage-to-cropland/en