By Siddharth Gokhale

Abstract

The last decade has seen the resurgence of a global debt wave, be it due to the oversight of policymakers around the world or a calculated decision of rapid, relentless economic expansion. Public debt has significantly contributed to the growth of this bubble. However, the growth of public and public debt-related interest payments has disproportionately impacted development of the Global South. The article analyses the cycle that these economies are caught in, with no way out. In attempting to avoid availing of the International Monetary Fund’s facilities and being subject to their austerity measures for this would risk socio-economic development, Southern economies prioritise payment of debt-servicing costs within their public expenditure plans, pushing expenditure on actual socio-economic developmental areas to lower rungs. The article argues that developing economies face a lose-lose situation.

The Zero Interest Rate Policy and the Growth of the Debt Bubble

“Controversial” is how most economists and finance professionals would describe the exercises in Quantitative Easing (QE) undertaken by central banks around the world after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008. QE was just one of the several measures undertaken globally to stir economic activity, the aim of central banks implementing this policy being to reduce the spread between the discount rate – the rate at which commercial banks borrow funds from the central bank – and the equilibrium interest rates in the overnight interbank loanable funds market. However, post-GFC, the QE was followed neither by its sister policy – quantitative tightening – nor any deleveraging exercise to reduce global debt, which economists had widely anticipated. Consequently, interest rates remained low worldwide after the crisis and credit became an attractive route for funding, with global dependence on debt increasing with time. Consider, for example, the interest rate declared by the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) Federal Open Market Committee, which most consider the signpost of prevailing global trends in interest rates. Even in December 2015, it maintained interest rates at the zero to near-zero levels they had been slashed to in 2008, while global debt during the same period rose by approximately 40%, from USD 142 trillion in 2007 (269% of GDP) to USD 199 trillion in 2014 (286% of GDP). The Fed did tighten its belt between 2015 and 2018 by increasing interest rates to a range of 2.25% to 2.5%, but only before reducing them in 2019 due to an economy that weakened in the face of a trade war with China, and further delivering two rate cuts in 2020, returning the interest rates back to 2008-levels and maintaining them there till Q12022. Meanwhile, global debt surged to USD 303 trillion in 2021 and to USD 315 trillion in Q12024.

Public Debt in Southern Countries

A sectoral breakdown of the growth in global debt reveals that global public debt has been on the rise. In the decade following the GFC, while total global debt rose to USD 169 trillion in H12017, public or sovereign debt rose to USD 60 trillion, spurred by governments facing the spillover of the crisis incurring high budget deficits to support massive bank bailouts and financial-stimulus packages. In the few following years, riding high on the back of even larger deficits, budgetary allocations and public expenditure during the pandemic, sovereign debt ballooned to USD 97 trillion in 2023. A deeper analysis of this surge in public debt reveals trends that draw the attention of economists and policymakers alike towards the economies of the Global South.

Developing countries already account for almost a third of global public debt, and the rate at which it is growing in these countries is almost twice that of developed economies. However, it is the case of Africa that best demonstrates the concern surrounding the growing public debt in southern countries. At the time this article is being written, public debt in the African region accounts for 67.2% of its GDP. Compared to the public debt-to-GDP ratio of developed countries, which stands tall at 107.9%, this number seems nominal; safe, in fact. However, interest payments loom dangerously over the region’s economy. For that amount of public debt, the region spends 16.7% of its net revenue or 3.4% of its GDP on interest payments, as against the 5.3% of net revenue or 1.9% of GDP spent by developed countries to service their debt. What such debt and debt-servicing levels indicate is that the economy has adopted a plan of public expenditure that increasingly prioritises debt obligations over all else. Understanding why this is a problem requires a two-step endeavour to reveal the dilemma of these economies.

The IMF and its Conditionalities

The first step is to understand why a public debt-ridden economy prioritises its interest payments. The traditional debt failure mechanism installed at the international level answers this question – if any economy is close to facing a debt failure or is actually facing one, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) usually steps in to provide financial resources to stabilise the economy. Such loans come with strings attached, called conditionalities. More often than not, these conditionalities, also called austerity measures for encouraging fiscal austerity, involve a combination of tight monetary and fiscal policies including lower public expenditure, higher rates of taxation and higher interest rates and structural adjustment of the economy towards a free market through privatisation, deregulation, and a floating exchange rate.

Critics have long argued that imposing such contractionary measures as a general prescription in cases of economic failure may have disastrous consequences on the borrower-nation, often citing the example of Malaysia, which had initially adopted IMF-inspired reforms in the immediate aftermath of the Asian Financial Crisis, resulting in a currency crisis transforming into a financial, and later into a general economic crisis for the country. They argue that austerity measures or their likes are not suitable for every economy and cannot be doled out as a standard recipe to prevent economic collapse lest it shall be a recipe for disaster.

Not only do these measures ignore the specificities of a certain economy, but they also ignore legitimate policy objectives of the borrower-nation, including sustainable development goals – Pakistan’s programme of energy transition that has been razed since it chose to avail of the Extended Fund Facility provided by the Fund lies testament to this. Contractionary reforms adopted by Pakistan included slashes on tax exemptions on renewable technologies, resulting in a 20% tax on solar and wind technologies, technologies on which rural off-grid households are majorly dependent, and a 12% increase in tax on the sale of imported electric vehicles, thereby also threatening the country’s international climate obligations.

Others argue that adoption of such contractionary measures also means a reduction in public expenditure in areas that are most necessary for the functioning of and social welfare in an economy, citing examples of several debt-ridden African economies which have availed of loans from the two Bretton Woods lenders and have subsequently experienced a drastic decrease in public-sector wage bills and public expenditure on fuel and electricity, pushing these economies to higher levels of unemployment and further into poverty. In fact, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has recognized that austerity measures involving a significant decrease in social sector spending can even lead to violations of a nation’s human rights obligations in international law.

Avoiding the Fund

Extension of resources and funds in situations of economic crisis conditional on the adoption of austerity measures risks social development within the borrower-nation, and it seems logical, therefore, for an indebted nation to prefer servicing the debt and bearing all entailing costs in priority to other expenses than defaulting and risking austerity.

However, this too has a similar, if not the same effect. Economies may try to avoid austerity by prioritising public debt interest payments but a necessary consequence of the same is deprioritizing public expenditure in other areas, some of which may be crucial for social development in that economy. Consider South Africa, having a public debt-to-GDP ratio of 73.9%, and 18.4% of its net revenue or 5% of its GDP dedicated to interest payments on the same, with the latter seeing a growing trend over the last decade. This has led to simultaneously deprioritizing public expenditure in other areas, creating a dent in its economy on other ends. The same duration which recorded the increased expenditure on interest payments also recorded a significant decrease in public expenditure on non-financial assets; infrastructural expenditure on education and other civic amenities including housing, water supply, and roads are noteworthy areas that faced these cuts.

Similarly, several economies had briefly adopted contractionary policies between 2015 and 2019 through public-sector wage bill cuts or caps, reduced subsidies, reduction in pensions, increase in consumption taxes, privatisation, and contractionary reforms in policies related to social security and labour flexibilization. The driving force of these policies being reduced public expenditure, they had pushed millions into poverty, also causing a global unemployment crisis, with a rollback in expenditure on healthcare infrastructure and services, the brunt of which had to be borne by populations left vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Between the Hammer and the Anvil

To say that developing nations with rising public debt are caught between a rock and hard place would be an understatement. Their dilemma arises from the fact that in case they default on their already high levels of public debt, they will almost certainly be bound to avail of loans from multilateral lenders, which force harsh austerity measures down their throats without care or concern towards the specificities of the economy, legitimate policy objectives and international obligations of the nation. There may also be a situation where developing economies, based on their eligibility, resort to other initiatives including the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative for the temporary suspension of debt service or the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative. Even then, it is not necessary for the relief so granted to consider the differentiated position of each economy, nor is it necessary that it address the underlying structural issues within the economy that led to the unserviceable levels of public debt; they merely kick the can down the road. In order to avoid such a situation, these economies prioritise servicing the public debt, but with growing levels of public debt, the costs of servicing such high debt levels also increases, making up a higher proportion of total public expenditure made in that economy, thereby causing lower public expenditure on other key sectors including food security, healthcare, education, environmental conservation and sustainability, and having a marginally lesser, if not the same level of impact as an austerity policy would have on these sectors.

The situation is precarious. What has been transpiring is a vicious cycle of debt that perpetuates economic inequalities, and that demands immediate reform. Public debt in countries of the Global South therefore ought to be managed in a better way than it currently is. Firstly, growth of public debt to levels that are not only unsustainable but also unserviceable must be avoided at all costs. By extension, where public debt is availed of, it must be sustainable, where investments made using the debt translate into returns with low opportunity costs. In any case, if there arises a situation of default or likeliness thereof, it must be resolved keeping in mind the principle of equitable development, and in a manner that is not blind to the differentiated position of these economies. Try as they may, under the current system of debt management, indebted developing countries have a bleak chance of ever becoming a developed country. This cannot sustain for much longer.

About the Auhtour:

Siddharth Gokhale is a fourth-year law student from Jindal Global Law School and a member of the Economics and Finance Cluster of Nickeled & Dimed. He is an avid reader of economics and is passionate about exploring the realm of international trade and investment law. He also has a keen interest in corporate restructuring, insolvency, and bankruptcy.

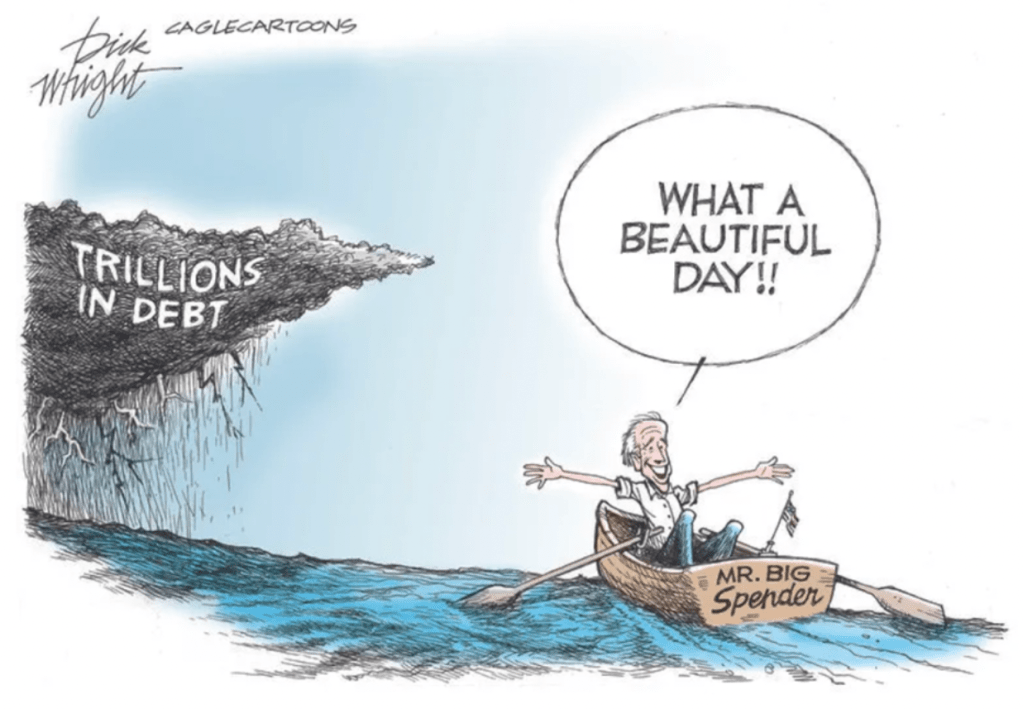

Image source: https://theweek.com/cartoons/977784/political-cartoon-biden-debt-spending