By Charudhi VG

Abstract

Abstract- This essay breaks down recent legislative metamorphoses in India’s criminal justice landscape through the enactment of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Act, Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, and Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita. The expedited legislative process, suspension of dissenting voices, and the assimilation of anti-terrorism provisions in the BNS that mirror the UAPA elicit apprehensions as to whether democratic principles are being observed. The phraseology and amplified jurisdiction provided through the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Act demand attention and critique, especially in the context of the dearth of substantial parliamentary deliberation. This article underscores the need for transparency – rooted in democratic ideals – while striking a harmony between security concerns and individual liberties to help provide for a criminal justice system that provides true justice.

Introduction

The Lok Sabha recently passed three new criminal laws, namely – the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Act, the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, and the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita thereby replacing the Indian Penal Code, the Evidence Act, and the Code of Criminal Procedure. The new criminal code is set to come into effect on 1st July 2024. This move by the government comes after several committee reports such as the Madhav Menon Committee and the Malimath Committee which recommended reforms to the criminal justice system. Through the new codes, Parliament seeks to replace colonial-era laws and help provide a criminal code that provides an improved criminal justice system. The incumbent government, while introducing the bills, specified that the new code seeks to eliminate “signs of slavery”. The fundamental aim of the new code therefore seems to be to – (1) erase the “colonial imprint” on India and (2) re-design a criminal justice system that was pliant to the whims of the government. While revising laws to decolonise the legal system and thereby eliminate laws that fall contrary to civil liberties and constitutional values is important, the new laws must be evaluated to help determine whether the goals of the centre have successfully materialised. Some revisions, however, fall diametrically opposite to the intended goals of the Legislative Assembly. They violate civil liberties, fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution, and eliminate previously established procedural safeguards.

Changes in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Act

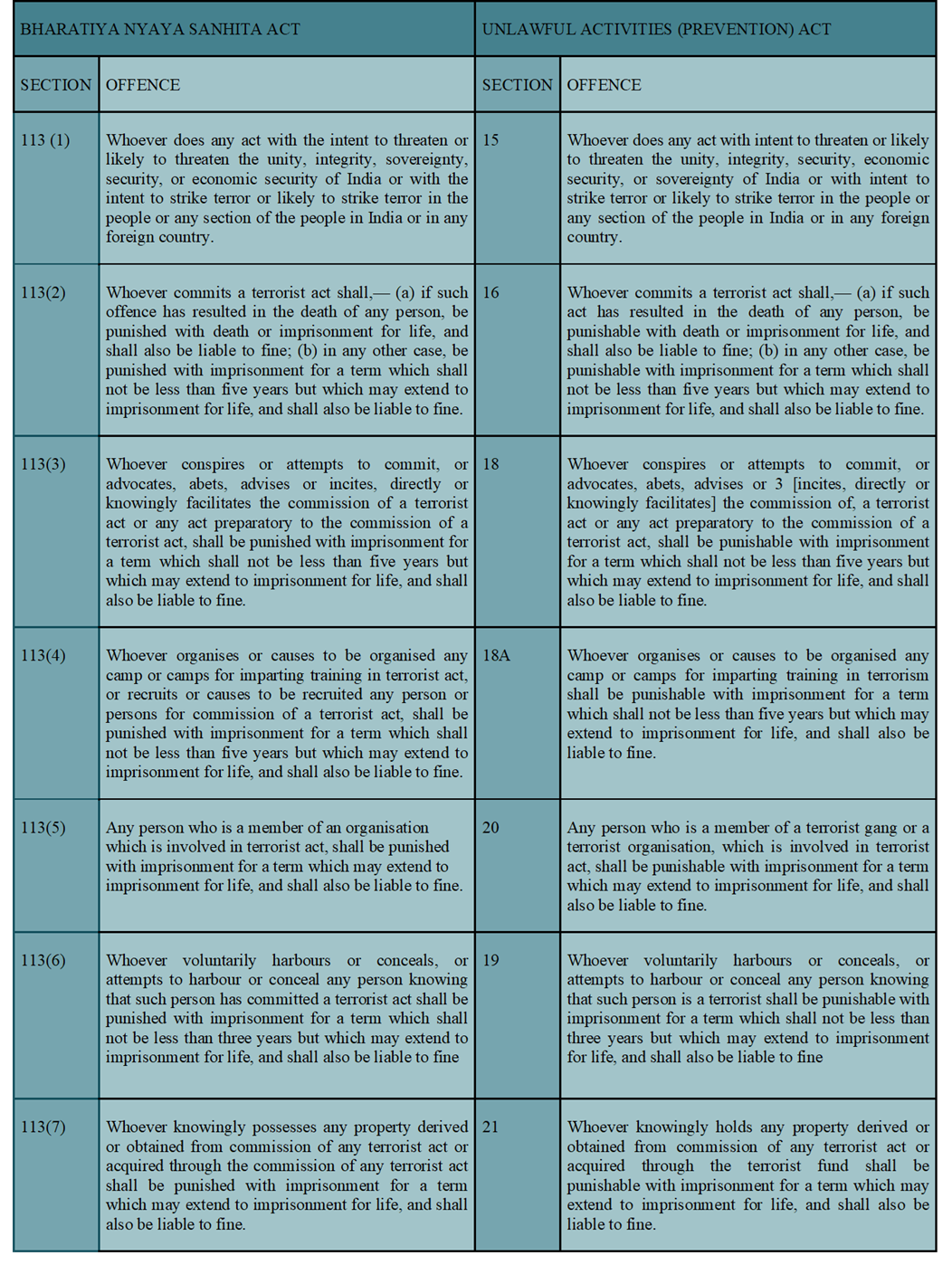

A key change in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Act (BNS) that embodies these violations is §113 of the statute. The move to incorporate “terrorist acts” within the ambit of a general penal code when a special law for the same is present through the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), is a peculiar one as the provisions largely overlap. While a case for a thin line of distinction can be made, the definition of a terrorist act itself is identical in the two statutes. The table below demonstrates the blatant duplication that Parliament has engaged in while incorporating terrorism as a crime in the BNS.

(Image Credit: Charudhi V G)

The few differences present between the two statutes are found in sections 113(4), 113(5), 113(6), and 113(7). The distinction lies in the terminology used in the statutes. The BNS strictly refers to “terrorist acts” alone, while the UAPA incorporates both “terrorist acts” and “terrorism”. This disparity continues as BNS penalises any organisation that engages in “terrorist acts” but UAPA penalises “terrorist organisations or terrorist gangs” alone. An analysis of the differences in terminology between the BNS and the UAPA therefore reveals a widened ambit conferred to the new penal code. While the merit in differentiating a singular terrorist act committed by a person/ organisation and a terrorist act committed by a terrorist/ terrorist organisation does exist, the penal consequences outlined remain the same. One can unfortunately only assume the rationale adopted by the government to incorporate terrorist acts within the ambit of the BNS as the bill was passed without discussion and deliberation. Considering the large overlap and the newly expanded jurisdiction conferred to the State, an important question arises – When a terrorist act is committed, under what statute do investigative authorities classify terrorist acts?

Legal Conflicts

Generally, when there is a conflict between general and special law the principle of generalia specialibus non derogant applies. This Latin principle translates to “things general do not derogate from things special”. This means that if there exist two laws – one with a general application and one with specific application – the special law would take precedence over the general law. Applying this principle while interpreting statutes is essential. Here, the UAPA forms the special law, thereby superseding general law. The principle, therefore, essentially extinguishes the need for terrorism in the general penal code. While the State may have intended to distinguish BNS from the UAPA and possibly even intend for the general law to supersede special law (which is allowed in certain exceptions) the same has not been clarified due to the lack of deliberation in Parliament. The only clarification that is available is through the explanation provided within the provision.

The explanation provided by §113 states that an officer not lower than the rank of a superintendent of police has the authority to decide which statute will apply to the “terrorist act” in question. However, the authority granted to the police to determine the applicable statute for a “terrorist act” lacks a specified rationale that is required for the decision-making process. This arbitrary power falls against the principles of equality espoused by Article 14. The Supreme Court specifically laid down that unrestricted discretion in the hands of the State to determine offences violates Article 14. As §113 does not prescribe any policy to restrict the discretion provided to law enforcement officials, it provides unbridled arbitrary power that allows the classification of offences without reason. A two-step process must be employed to legally establish that the classification used is backed by reason. First, an intelligible differentia between the two categories must exist, and second, a rational nexus between the differentia and the goal of the statute must exist. Unfortunately, even after examining the law as per this process, there is no rational nexus between the provisions and the goal of the statute. The lack of reason therefore provides unrestricted discretion in classification and falls against the spirit of Article 14 of the Constitution.

At this juncture, considering the conflicting legal nature of §113 of the BNS, it is essential to evaluate the deeper differences and problems that arise out of incorporating terrorism as a part of the code. The UAPA is known for its draconian nature and its scant procedural safeguards. The Apex Court has stated bluntly that “jail not bail” is the rule for the UAPA. However, BNS circumvents the safeguards established through the UAPA. It achieves this by – (1) allowing courts to take cognizance of terrorist acts without sanction letters, and (2) widening the ambit of terrorist organisations to any organisation.

Circumventing Safeguards and Reinforcing Draconian Law

§45 of the UAPA forms a procedural safeguard that does not permit courts to take cognizance of a terrorist act unless it has received previous sanction by the central or state government as per the specifications of the statute. As there are no exceptions that have been created for terrorist acts under the BNS, the ordinary criminal procedure would assumedly follow (despite generalia specialibus non derogant) and create a procedure that does not require the sanction of the government. This act therefore strips an extremely sensitive offence prone to misuse, of structural safeguards. The omission of a requirement for special government sanction for an anti-terror provision is perplexing, to say the least. The lack of substantial parliamentary discussion on the bills suggests an intent to eliminate the paper-thin safeguards in a law that is already strongly criticised for its draconian measures.

Regarding the widened ambit of organisations that come under the attack of anti-terror law Sections 35, 36, and 37 of the UAPA must be accounted for. §35 of the statute outlines the procedure through which a terrorist organisation is notified and mandates that the requirements as specified by the statute are fulfilled. Further, after the notification is issued it must be presented to the Parliament. The procedure for de-notifying these organisations is outlined in Sections 36 and 37. By eliminating the word terrorist from organisations and widening its ambit, BNS has rid itself of procedural requirements. As a facet of the law, procedure helps ensure order and consistent application. Stripping procedural law from provisions by reframing laws is alarming as it may devolve into stripping civil liberties.

It is disheartening that, instead of pursuing meaningful reforms in the criminal justice system, the State has chosen to enact laws that mirror the draconian nature of the UAPA in addressing terrorism. The definition of a terrorist act as employed by the UAPA encompasses subjective and overbroad terminology that could be weaponised. Mirroring these very subjective terminologies into the BNS without the safeguards present in the UAPA raises serious concerns about misuse and laws being used to blur the lines between dissent and terrorist acts. The hostile approach towards reform of the criminal justice system undermines the dire need for nuanced legal frameworks that balance security concerns with the protection of individual liberties.

Democratic Backsliding and the Creation of a Police State

It is essential, however, to acknowledge the limitations of this analysis. While it is based on legal provisions and an analysis of the same, legislative intent and the lack of deliberation in Parliament surrounding the three new laws severely hinders a thorough analysis of the statute. This raises an essential question on the nature of India as a deliberative democracy. Tarunabh Khaitan in his work on reforming the pre-legislative process opines that a deliberative democracy helps incorporate equality by treating all individuals fairly and providing them with a role in the decision-making process while establishing a system through which their concerns are addressed while employing reason. The words fair and reason form a central part of democracy and the democratic functioning of the State. The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Act not only raises concerns due to its reproduction of oppressive laws but also due to how it was passed. Discussion and procedure help democracies thrive, and both have been pushed into the ground.

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Act, the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, and the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita were passed by the Parliament in the absence of 97 MPs who were suspended after demanding a statement on the breach of Parliament. The few opposition MPs who were present while the Bills were being passed criticised it for turning the country into a “police state”. It is essential to note that the integrity of a constitutional democracy ruled by a majoritarian government balances on whether it follows the unwritten rules of conduct of a democracy. Sujit Chaudhury in his work on Opposition Rights in Parliamentary Democracies describes these “unwritten norms” as rules that help restrain majoritarian governments from employing their power to the fullest extent permitted by law in a manner that disables the opposition and therefore, the democracy itself. A flagrant violation of these norms followed by the introduction and passing of bills by the Parliament threatens to rip the constitutional fabric of India.

Conclusion

The enactment of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Act and its counterparts, the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam and the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, therefore, marks a significant shift in India’s legal landscape. While purportedly aimed at reforming the criminal justice system, the manner in which these laws were introduced and subsequently passed raises serious questions about the democratic process in the country. The rushed legislative process, lack of deliberation, and the silencing of dissenting opinions undermine the principles of a deliberative democracy. The incorporation of anti-terrorism provisions, mirroring those of UAPA, without adequate safeguards, heightens concerns about potential misuse and the erosion of civil liberties. The ambiguous language employed coupled with the widened ambit of these provisions in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Act have a critical impact on individual rights and constitutional values. The “signs of slavery” that the State purportedly aims at erasing, merely repurposes colonial power, aggravates the ability to misuse it, and lays it out on a silver platter for law enforcement officials to exploit. There is therefore a dire requirement and a cavity of justice, fairness, and procedure in the criminal justice system which existed before the BNS and continues to exist.

Legislative reforms aimed at reforming existing anti-terror law, including the incorporation of increased procedural safeguards within UAPA and resolving the vague language employed within it (an example being “to strike terror”) would help address the shortcomings of anti-terror law. Individual liberty, fundamental rights, and the values enshrined in the Constitution would persevere. Anti-terror law within the BNS however, serves no evident purpose except increasing leeway to abuse procedure established by law and should be read down by courts unless the State demonstrates that its functioning will not violate the basic structure of the Constitution.

Author’s Bio

Charudhi VG is pursuing her third year, BA LLB at Jindal Global Law School. Her interest areas include constitutional law, criminal law, data privacy, and competition law.

Image Source: Charudhi VG