By Aman Chain

Abstract

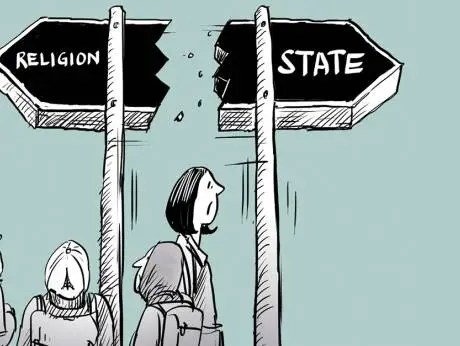

The concept of secularism is differently used by different countries, their political parties and even the courts. This article will highlight the flawed understanding of secularism that prevails in today’s discourse. The complex intermixing of the Religious and Secular spheres, which the concept of secularism strives hard to distinguish, will be thoroughly discussed. While determining the scope of religion, this article will highlight the stark difference between the understanding of religion by different scholars and the way courts perceive and use the same, causing chaos and confusion.

Article 25 of the Indian Constitution grants to all its citizens the freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice and propagate any religion. But this right is not an absolute one. Along with a few reasonable restrictions, it also allows the state to regulate any economic or financial matter related to religious institutions or denominations. Thus, follows the idea of a distinction between the two ‘spheres’ namely religion and secular. There has been systemic violence among those following different religious and cultural ideologies: several historical events in India such as the Partition, Babri Mosque Demolition and the Gujarat Riots of 2002, have cemented our faith, and expectations from the word ‘secularism.’ But in reality, the label of ‘secular state’ not only failed to stop this violence and failure of multiculturalism but instead contributed to it, as every religious practice of different communities was questioned on the anvil of secularism. Thus, it becomes imperative to look at the word from a critical lens and raise the right question. Part I and Part II of this article put forward different arguments and facts, that aim to explore how secularism is practised on the ground in the Indian context and to determine whether this hope and faith in the word ‘secularism’ are valid.

Firstly, one needs to understand why this distinction of spheres is destined to collapse in the Indian context. This further raises questions on the meaning of the word ‘secularism,’ which will be discussed at length in this piece. Secondly, the article will also look at one of the main reasons stated for the failure of secularism in India, which can be explored by tracing the footprints of the birth of secularism. This will be dealt with in the second part of this article.

The Dilemma of the Religious and Secular Spheres:

Several states practice different forms of secularism. For some, such as France, secularism entails a separation between religion and the state, and thus a complete prohibition on religious expression in the public domain. The second, which India follows is the vague/blurred separation of religion and the state, in which the state is not allowed to interfere in religious matters unless it concerns public safety and the individuals are free to profess and practice their religion publicly. However, for this distinction between the two spheres to exist in India, we must first understand how it is defined in the Indian context. According to Rajeev Bhargava, secularism in the Indian context is quite different and is not ‘homogenous’ in nature like the West. Gandhi believed that mutual respect for every religion was more important than mere tolerance. But, if the entire concept of secularism is based on the idea of tolerance, is it possible to follow Gandhi’s idea of secularism? This question will be addressed in the following part of the paper.

The dilemma of the two spheres becomes more complex in India because of the confusion around the definition of religion. This problem is further exacerbated when we try to look into the definition and meaning of ‘Hinduism,’ the majority religion of India. Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, on one hand, envisioned India as a secular state and on the other hand, while describing ‘Hinduism’ as a faith, calls it vague and something difficult to define. One of the well-known academicians, Jakob De Roover, in his criticism of Nehru, claims that if something is ambiguous and tough to define, how can one distinguish between religion and secular/state? Shashi Tharoor, a renowned Indian Politician and author, in his book, Why I am a Hindu, defines ‘Hinduism’ as something which is both, less and more than a set of “theological beliefs.” Tharoor’s definition of Hinduism is broad. According to him, an astika (pious: one who accepts the holiness of the Vedas and believes in god) is a Hindu, as is a nastika (impious: one who rejects the existence of the god or any of these credos). The astika Hindu can follow any of the six schools of philosophy known as the “Shad Darshanas.” The nastika Hindus can follow the “Charvaka School,” which is devoted to materialism and wealth. Tharoor’s definition of Hinduism leaves room for misinterpretations, and his universalisation of Hinduism is problematic on multiple levels. He goes on to say that even Buddhism and Jainism are included in the definition of ‘Hinduism.’ The problem with Hinduism being universalised is that the ‘exclusivity’ of religion is lost, and there are no boundaries within which one is a Hindu and outside of which one is not, thereby making it difficult for the courts to determine what is religious and what is secular.

Determining the Scope of Religion:

In this religious-secular dilemma, the ‘scope of religion’ is always a problem for any state to decide. In order to prove a community’s beliefs and religious practices, states and courts must follow a set of criteria. The following section will analyse how in India, the courts use the criterion of ‘essentiality’ in religious practices. To follow this criterion, states/courts must first determine which types of clothing, symbols, jewellery, and language are religious and which are secular. Consider the hijab, turban or the Cross which is worn by a few religious communities in several countries. A secular state can argue that a Muslim woman should not wear a hijab or a Sikh man should not wear his turban in educational institutions, which is similar to the recent hijab row controversy in India. The argument presented in this article is more general and is not limited to the Indian/Asian context, but includes Europe as well. A headscarf or a cross becomes a religious symbol only when the person wearing or using it has ‘faith’ in it, believes in the meaning of wearing that cross, or understands the theology behind it. Others who wear a headscarf (a religious symbol for some) but have no reverence towards it will treat it as a piece of cloth. Many people wear a ‘cross’ for aesthetic reasons and can grow long beards because they look good with it. How can the state determine which practices are religious when the meaning and interpretation of such practices are so subjective?

There are two major issues with courts determining the scope of religion. Firstly, it may lead to the ignorance of the minority. The idea of religion in any community is shaped by its historic domination by a majority community. This implies that any practice followed by the majority community can easily be proven to be religious, while practices not considered “religious” by the majority can easily be ignored. Thus, if a distinction for classification is made, the religious beliefs and practices of the minority will always be at stake. This model would have worked well in a more homogeneous society, but not in a diverse culture, as in the case of India. As a result, courts may tend to accept the dominantly prevalent practices as religious, thus defeating the entire purpose of “state neutrality and religious freedom.” One cannot expect the judges to develop some kind of scientific formula or theory that will limit religion in secular spaces of the state. They on the contrary come to a conclusion influenced by the consensus prevailing in the society while determining the scope of the religion. This can be proved by the fact that a court’s decision will most probably change if the society or the majoritarian religious community undergoes changes.Second, if there is diversity, there will be differences of opinion among experts from various fields. This would subsequently make it difficult for the judges to reach a consensus. It is important to note that even if the courts reach an agreement on the “scope of religion,” it will only be valid for a specific period in a specific society. For instance, one could consider the case of the United States and India for that matter. The first amendment to the United States Constitution stated that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” In the case of India, there is Article 25, also known as the secularism article. Now, for judges to hear cases that fall under the purview of these two articles and determine the scope of religion, they must first know what religion is and what practices constitute religious belief. For which, there is no consensus and with time, keeps changing. Because to create a space completely devoid of religion, the court will first have to enter that religious space to determine whether the concerned practice or symbol has any religious significance or not. The Indian courts are a step ahead in this case. They decide not only the religiosity of the symbols or customs but go to the extent of determining if it is “essential” to that religion or not. As a result, they completely enter the theological realm of religion. This demonstrates the paradox of a “secular court” deciding on the religiosity of a symbol. It is therefore rightly said that “Wherever the secular state is called on to decide on the religiosity of symbols, it embarks on a journey that ends up within the realm of religion.”

About the Author

Aman Chain is a second- year law student at Jindal Global Law School. His areas of interest are queer studies, Constitutional law and intersections of religion and law.

Find Part 2 here