By – Anisha Jyotirmayee

Abstract:

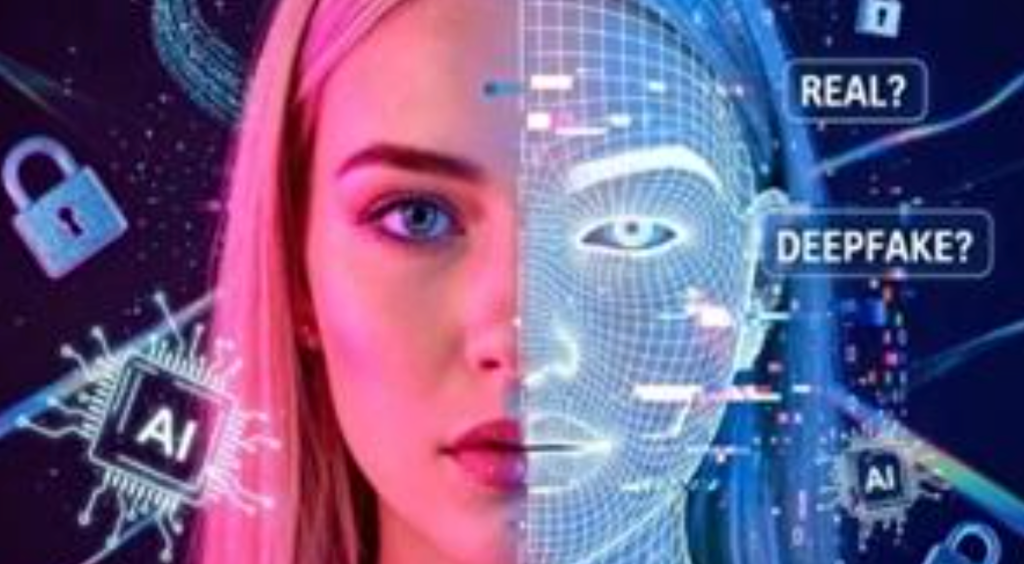

The rapid expansion of deepfake technology has introduced new forms of digital harm that disproportionately affect women. While deepfakes are commonly framed as a problem of misinformation, their most prevalent use recently has been the creation of different kinds of non-consensual sexual content, depicting a form of gendered digital violence. This article examines deepfakes through a research and case study perspective, arguing that they represent sexualized and structural harm. Drawing on legalities and scholarship on image-based abuse, the article analyzes the gendered patterns of deepfake production, as well as the psychological and social impacts on victims with real-life examples, and the ways in which synthetic media intensifies existing patriarchal mechanisms of control and surveillance. It further critiques the inadequacy of current legal and platform-based responses, highlighting how gender-neutral approaches to AI governance fail to address gender-specific harms. The article concludes by advocating for gender-sensitive AI regulation grounded in consent, accountability, and justice.

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been viewed as a revolutionary force for efficiency, creativity, innovation, and other positive social values in societies across the world. This is done through improving education, addressing biases, enhancing public services, empowering healthcare delivery, and furthermore. AI has also influenced how we think about inclusion, equality and accessibility in society. However, alongside its benefits, AI has produced new ways of harm towards women, which is far more accessible and easier to execute.

The quick pace at which AI technologies have developed has dramatically changed the way images and identities shown in virtual environments. Among the most disturbing things happening today is the fast growth of deepfakes, which, by definition, refer to AI-generated synthetic content meant to mimic real individuals. According to research conducted by deepfake detection firm Sensity AI (formerly Deeptrace) and subsequently updated by other cybersecurity organizations a report indicated that 96 percent of deepfakes observed were of non-consensual sexual deepfakes, and 99 percent of these images were of women.

This phenomenon represents a new form of gendered violence and normalises this kind of bias, which has a disproportionate risk to women and girls. Deepfakes can also be understood within the existing structures of patriarchy, where women’s bodies have historically been subjected to surveillance, control, and sexualised scrutiny. This new form of gendered violence adds on to the already existing violence that women face in their daily lives. The law exists against the existing forms of violence, but is due to have a legal legislation defining this as a form of crime.

The emergence of social botnets enhances the speed at which the content is spread and it creates a blur between fact and fiction. Deepfake abuse constitutes a form of sexualized, structural violence that reinforces gender hierarchies and threatens women’s participation in public, political, and professional life. Deepfakes can also be defined as a socio-political phenomenon that is embedded in power relations, exploring their gendered patterns of use, credibility, and authority of traditional social institutions and the subsequent failures of existing legal and technological responses.

Understanding Deepfakes

Deepfakes do not require any expertise, as this technology uses deep learning methods, including generative adversarial networks (GANs), that, after examining thousands of pictures of a single individual, make a digital imitation that is very similar to the original. The technology to create deepfakes is accessible and has become very widespread, making it easier for anyone to perform this digital imitation with simple apps available on various websites.

According to UN Women, a global survey found that 38 percent of women have personal experiences of online violence, and 85 percent of women online have witnessed digital violence against others. The survey also suggested that this is not just restricted to the harms happening on the screens; it easily spills into real life, where it escalates, and AI tools facilitate blackmailing and stalking women. This marks a shift from older forms of image abuse, such as leaked private photos, to a more insidious form of fabricated sexualization, where even women who have never taken intimate photos can be targeted.

The Gendered Pattern of Deepfake Abuse

The overwhelming majority of deepfake pornography targets women. Victims include women with fame in various domains and, increasingly, ordinary women and girls. Women’s bodies have long been treated as objects for visual pleasure, whether it be in movies or in real life, and deepfakes simply automate this exploitation. Men are occasionally targeted by deepfakes, but the motivations differ; it is often for satire, political manipulation, or financial fraud.

When women are the victims, it is primarily for sexual humiliation and control. This difference reflects broader gendered power structures in which a woman’s value within the social sphere is measured through sexual respectability; therefore, the effects of sexualized deepfake attacks are more detrimental for women. Likewise, the distribution of deepfake images focuses mostly on women who are prominent within the broader public sphere. This issue makes journalists, as well as female politicians, common targets of deepfake attacks, as it creates an atmosphere of silencing women.

Deepfake pornography is often dismissed as “just images,” but this framing minimizes the profound harm it causes. In reality, deepfakes constitute a form of image-based sexual abuse, comparable to other forms of non-consensual pornography. The victim’s face, identity, and social existence are hijacked and inserted into a sexual narrative without consent. UNICEF describes deepfake abuse as a form of digital sexual assault. The trauma experienced by victims includes emotions of shame, fear, anxiety, and loss of control.

Social impact

A recent case at the XIM University in Bhubaneswar highlighted the institutional failures that accompany incidents of gender-based digital violence. A student who was caught making deepfake pornography of peers was favored by the authorities and advised to claim mental instability. This response reflects a broader tendency to individualize and medicalize wrongdoing instead of confronting it as a form of gendered harm enabled by technology. This is just one out of thousands or lakhs of cases that either arose and were declined, or never garnered any attention at all.

In similar cases globally, victims of deepfake pornography have reported severe reputational harm and life disruption, prompting courts to intervene. For example, in Australia, a man named Anthony Rotondo was taken to court by the federal eSafety Commissioner for repeatedly uploading and refusing to remove deepfake pornographic images of multiple women without their consent.

The Federal Court fined him a total of around AU$343,500 for violating the Online Safety Act and contempt of court when he ignored removal orders. The identities of the women were protected by the court to prevent further harm. The Delhi High Court granted an injunction against the circulation of non-consensual deepfake pornography, ordering platforms like Meta and X to remove the content and disclose the user details of individuals responsible for dissemination.

Legal landscape of India

India’s legal framework currently lacks any kind of deepfake-specific legislation. Instead, victims and prosecutors typically rely on existing cybercrime and defamation statutes to address deepfake harms. The commonly invoked provisions include the Information Technology Act, 2000, provisions on obscene or morphed content, as well as the Indian Penal Code (IPC) sections for defamation, identity fraud, and sexual offenses.

Despite these tools, critics argue that the law is insufficient because it still has not directly criminalized AI-generated synthetic media. Enforcement mechanisms are often reactive rather than preventive; victims frequently encounter delays in takedown and redress. Currently, according to the Right to Privacy and Dignity, there has been a faster removal of non-consensual deepfakes, which strengthens individual dignity. However, the simultaneous implementation has not been as effective due to the lack of awareness and also the silent nature of the crime, making it harder to find the perpetrator.

Conclusion

Deepfakes illustrate a new frontier in gendered violence, extending power imbalances and harassment into digital spaces. Although deepfakes represent one of the most disturbing intersections of artificial intelligence and gender inequality, resistance is growing. Researchers have developed some and are still developing AI detection tools, activists are pushing for stronger laws, and feminist technologists are advocating for ethical AI design.

Social movements are demanding stricter, specific laws that treat non-consensual deepfake pornography with the same severity as other forms of sexual violence. This includes advocating for platforms to remove such content immediately. Initiatives such as the EU’s “StopFakeNews” are also rising to educate the public on identifying manipulated content, fostering a more critical approach to media consumption.

Author’s Bio:

Anisha Jyotirmayee is a student of Journalism and Media Studies at O.P Jindal Global University. Starting with an inclined interest towards literature, she started writing research-based articles that defined and worked with real social issues. She has also embarked upon interviews and panel discussions with experts and marginalized groups. With an interest in literature, she also dances, plays the guitar, and is a columnist for Swabhimaan and Nickled and Dimed.

Image Source: https://www.openfox.com/news/how-blockchain-secures-chain-of-custody-in-an-era-of-ai-deepfakes/