By – Siddarth Poola

Abstract

Large-scale infrastructure and extractive projects are routinely justified through the language of development, national interest, and economic necessity. Yet repeated instances of displacement, ecological degradation, and community impoverishment raise a persistent question: development for whom? Drawing on investigative reporting and civil society documentation relating to coal and infrastructure projects associated with the Adani Group in India and Australia, this article argues that development increasingly operates less as a pathway to collective upliftment and more as a discursive shield. It deflects blame for dispossession while legitimising the transfer of land, resources, and decision-making power away from local communities and towards private capital. Rather than treating displacement as an unfortunate by-product of growth, the article situates it as a predictable outcome of a political economy that prioritises extraction, speed, and certainty over social reproduction. In doing so, it highlights how law, bureaucracy, and nationalist rhetoric work together to normalise loss while presenting it as inevitable progress.

Introduction

Development is rarely introduced gently. It arrives with surveyors, notices, and the implicit suggestion that what exists on the land is provisional. Villages, forests, and livelihoods appear, in official narratives, as temporary arrangements awaiting rational reorganisation. When displacement follows, it is framed as an unfortunate but necessary step on the road to prosperity, even when prosperity remains stubbornly absent.

The New Yorker’s account of a coal mine that razed a village and shrank a forest in India offers a stark illustration. The village is not portrayed as a site of social life or economic activity, but as a spatial inconvenience that needed to be cleared for extraction to proceed. What disappears alongside the village is the assumption that development must tangibly benefit those most directly affected by it.

This article proceeds from that disjunction. It examines how the language and practice of development are used to justify land acquisition, forest diversion, and eviction in ways that systematically prioritise capital-intensive projects over community well-being. The argument is not that development has failed to uplift communities, but that upliftment has been structurally sidelined in favour of accumulation, with the state acting as facilitator and legitimiser rather than neutral arbiter.

Land, Law, and the Quiet Reclassification of Value

One of the most revealing aspects of contemporary development governance is the way land is transformed before extraction even begins. Legal status, rather than physical reality, determines whether land is protected or available. The Reporters’ Collective documented how the Gujarat government requested the Union government to remove forests from conservation status to enable Adani-linked projects, effectively rewriting the land’s legal identity. The forest did not change. Its classification did.

This manoeuvre matters because it shifts the debate from whether extraction should occur to how quickly approvals can be processed. Environmental law remains intact in form, but hollowed out in function. The Guardian’s reporting on coal mining in the Hasdeo Arand region shows how even ecologically significant forests can be incrementally opened to mining through phased clearances and compartmentalised impact assessments. Social and ecological costs are acknowledged abstractly, while approvals proceed concretely.

In this framework, development does not confront the question of whether land should be extracted. It manages the process of making extraction appear administratively routine. The law does not block dispossession. It organises it.

Eviction, Compensation, and the Conversion of Harm into Procedure

When land is reclassified and cleared on paper, displacement becomes a logistical task. The eviction drives in Assam documented by Citizens for Justice and Peace demonstrate how administrative categories such as encroachment and illegality are mobilised to justify the physical removal of communities. By the time bulldozers arrive, the moral work has already been done. Residents are no longer people losing homes, but obstacles being removed.

Land Conflict Watch’s account of disputes surrounding Adani’s Dhirauli coal mine further illustrates how compensation functions within this system. Compensation is framed as closure, even when it fails to account for long-term livelihood loss, social disintegration, or cultural displacement. Once money enters the picture, harm is treated as resolved, and continued resistance is portrayed as irrational rather than political.

What is striking is not the inadequacy of compensation, but the confidence with which it is presented as sufficient. Development discourse relies heavily on this confidence. It converts complex social relations into figures, allowing dispossession to be balanced on spreadsheets rather than addressed as a structural loss.

Indigenous Presence and the Performance of Inclusion

Indigenous communities complicate development narratives because their relationship to land resists easy monetisation. This resistance is managed through procedural inclusion rather than substantive power. Stop Adani’s documentation shows how Indigenous rights are acknowledged in principle while being undermined in practice through diluted consultation and constrained participation.

Consultation processes often occur after projects are effectively locked in. Community meetings become evidence of compliance rather than opportunities for meaningful dissent. The New Yorker notes how villagers opposing coal mining were framed as anti-development, a label that strips their resistance of legitimacy and recasts it as emotional or misinformed.

Australia offers a parallel. The Australia Institute’s record of Adani-related controversies details repeated regulatory concessions and political interventions made in the name of economic urgency. The Monthly situates these choices within a broader cultural commitment to coal, where extractive projects are framed as synonymous with national prosperity and stability.

Across contexts, Indigenous presence is acknowledged just enough to be procedurally neutralised. Inclusion becomes a formality that enables exclusion.

National Interest and the Dispersal of Responsibility

The final layer that stabilises this model is narrative. Development is framed as national interest, rendering opposition suspect by default. The Hindu reports opposition criticism describing the government’s facilitation of corporate expansion as a fire sale of national assets to favoured private players. Yet the charge of being anti-national is more often directed at those resisting displacement than those profiting from it.

India Today NE’s opinion piece illustrates how local leaders and bureaucrats play a key role in translating national priorities into local outcomes, often at the expense of their own communities. Responsibility is diffused across institutions, making it difficult to locate accountability even as outcomes remain consistent.

In this narrative economy, development absorbs blame. When communities suffer, the explanation is not policy choice but necessity. There was no alternative. The market demanded it. The nation required it.

Conclusion

The cases examined here suggest that development is not simply a goal pursued imperfectly, but a framework that actively manages and legitimises loss. Land is reclassified, people are evicted, forests are diverted, and resistance is reframed, all while the promised upliftment remains abstract and deferred.

What makes this model durable is not its success in improving lives, but its ability to present dispossession as reasonable, lawful, and inevitable. Development does not need to deliver prosperity to function. It needs only to provide an explanation that deflects blame and keeps the accumulation moving.

Progress, in this sense, is not measured by who benefits but by how smoothly loss can be administered.

About the Author

I’m Siddarth Poola, an undergraduate student doing law in Jindal Global Law School, with a deep interest in Water Sports and Sports Law.

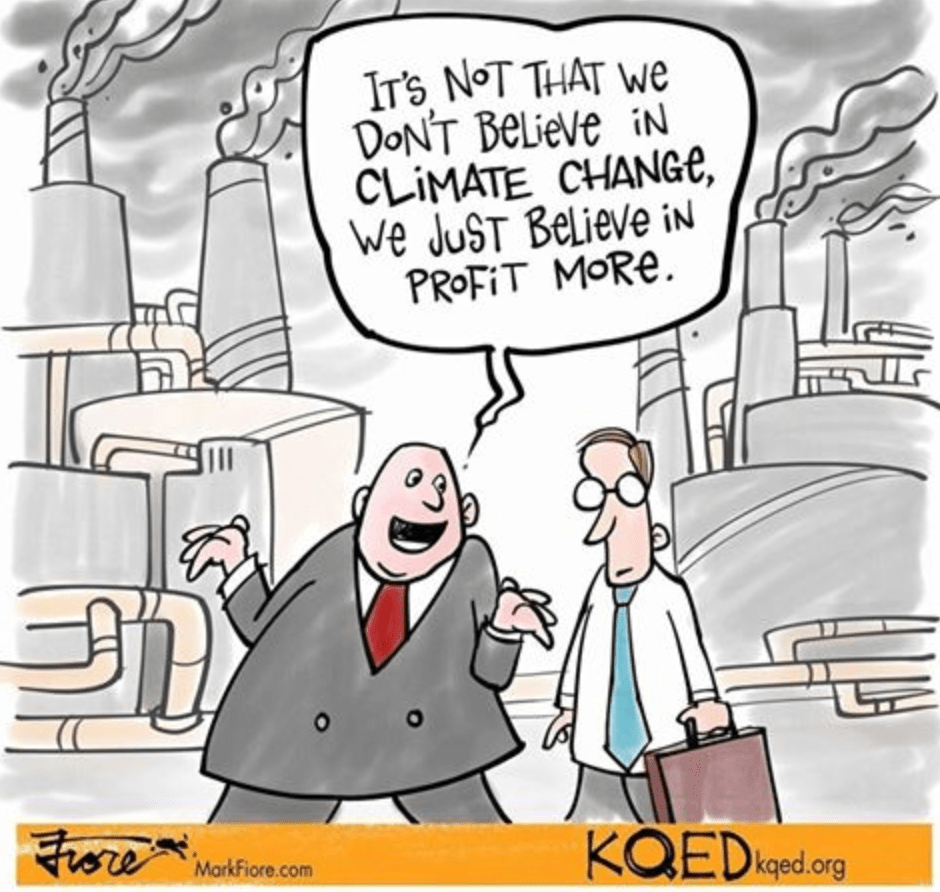

Image Source : https://skepticalscience.com//pics/2016Toon33.jpg