By – Akshara Gupta

Abstract

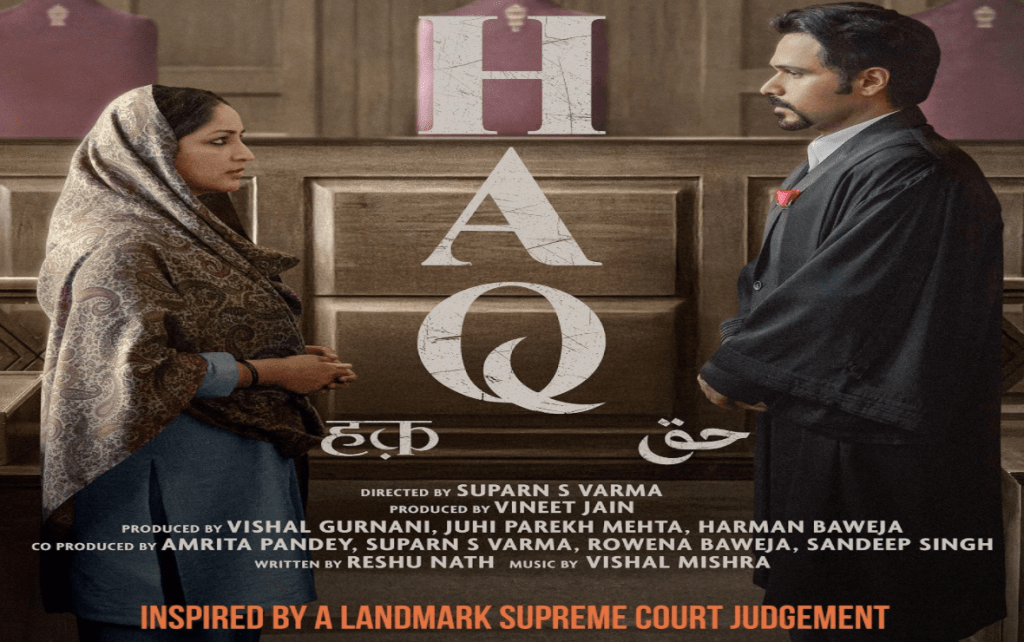

Haq is a courtroom drama based on the real-life case of Shah Bano (1985), which aims to examine the gap between law and gender within religious communities in the country. The film, through its female protagonist, tries to present the current lacunae in the social institutions as well as formal government structures that often disregard women’s sufferings. Haq examines the role of societal conditioning, regular negligence of the administration, and lack of meaningful institutional support in enabling injustice. It showcases how injustice can sometimes show itself as an abduction of voice, agency, and self-respect. Therefore, the film points out the gap between the law’s intention and the actual situation on the ground by giving the concept of dignity the status of a governance problem rather than a mere moral ideal. It highlights the struggle of a woman who finds abode in her husband’s heart and desires only his love. Even after dedicating her 17 years to him, he did a second marriage and that shatters her and compels her to stand for her rights. ‘Talaq Talaq Talaq’, the strength of these mere three words is questioned by the protagonist, and these words changed her whole life. When the whole society backlashes her, it’s only her confidence in herself that helps her sail through. This film also highlights the bifurcation in law as being declared Hindu and Muslim.

Introduction

“Mera Haq bheek nahi hai…. ye meri pehchaan hai”. This very dialogue signifies the lost dignity and self-respect of the female protagonist and how a woman must fight for her rights throughout her life. The Supreme Court of India made an important enquiry in 1985: “Is the right to life and dignity of a woman guaranteed by the Constitution or by the religious texts followed by the woman?”

The movie Haq, starring Emraan Hashmi and Yami Gautam, looks at this very tumultuous period in Indian legal history. The movie, with Yami Gautam’s very subdued and thoughtful performance, moves the focus from institutionalized injustice to the private realm of marriage, body, and memory, where inequity is experienced.

The movie Haq, starring Emraan Hashmi and Yami Gautam, looks at this very tumultuous period in Indian legal history. For a long time, Indian cinema has shown the existence of injustice in society through a number of courtroom dramas, police investigations, and crime documentaries. However, Haq is different from all these very well-known genres. It shows injustice as something that emerges when people are denied their dignity and self-respect, and not merely when the law is violated. The movie, with Yami Gautam’s very subdued and thoughtful performance, moves the focus from institutionalized injustice to the private realm of marriage, body, and memory, where inequity is experienced.

It asks a very disturbing question: what if suffering becomes normalized to the point where it stops being seen as exceptional? In doing so, the movie comes across as a very personal and emotional reckoning rather than a mere legal case.

Gender, Dignity and Justice

In Haq, silence is not emotional but more administrative in nature. The protagonist’s suffering is not registered as a public problem because it cannot easily be related to official categories. But what it mirrors is a structural problem in the governance system, as the framework seems to be limited, which is used by the institutions to identify right or wrong. The movie Haq, which is based on the case, Mohammed Ahmed Khan versus Shah Banu Begum (1985), also highlights the injustice suffered by the women in the 20th century, where long-term psychological harm, coercion, and emotional trauma could never easily fit into reporting systems.

This movie makes the argument that visible catastrophes are easier to handle than the daily life pain, which women are consequently compelled to carry in private. Amartya Sen argues that justice must be understood, not merely as institutional design, but as lived social reality. And then the legal system deprived women of experiential justice. That is how gradually women are trained to internalise injustice, rather than confront it.

Emotional Harm and Moral Authority

In the context of a Courtroom the audience is not asked to evaluate the evidence or determine guilt; rather, it is allowed to invade the protagonist’s emotion and psychological realm. Through various instances, the protagonist has to face backlash in society for registering a case against her husband, who, as per him, committed ‘sawaab’ or a virtuous act by engaging in a second marriage. The whole society disregarded her and her family, and fighting for Justice became equivalent to walking on burning coals. Many feminist theorists like MacKinnon have similarly shown that emotional and domestic harms against women remain invisible to legal and policy frameworks.

In this way, the movie creates an alternative form of authority. The protagonist’s perseverance becomes a kind of testimony, and suffering becomes a kind of knowledge. As a result, it expands the meaning of injustice beyond what is legally quantifiable.

The Conflict between Personal Law and Constitutional Morality

The film dramatizes the legal battle between Section 125 of the CrPc, which guarantees maintenance to all wives, and Muslim personal law, which was argued to exempt Muslim men after they have divorced their wives according to Sharia law. It shows how a battle for maintenance becomes a religious battle, which raises questions against secularism and its execution.

Shazia Banu (Yami Gautam) begins by asking for financial support for survival, but ends up fighting for her dignity. This film redefines maintenance, which was not about money, but about acknowledgement that a woman’s labour and life in a marriage cannot simply be discarded by Triple Talak.

Double Burden: Intersectionality and Isolation

The film also presents the double burden, which is faced by minority women in the country, who face a double struggle, which is fighting patriarchy within their community while simultaneously facing marginalization from the whole society. Various stereotypes are highlighted in the film by the subjugation faced by Shazia. The movie explores the vulnerable situation of a Muslim woman who ends up engaging in a war on two fronts. On one hand, she is struggling against the patriarchy of her own community, which sees her legal suit as a cultural betrayal. On the other hand, she is confronting a secular establishment, which is frequently ready to exploit her struggle to portray her community in a negative light rather than sincerely freeing her.

It is the “double burden” that the movie tackles sensitively. Shazia Bano is portrayed more as a victim of political polarization than as a victim of religion. In some touching scenes, she is shown to be isolated from her neighbors and the religious leaders who are accusing her, who view her individual rights as an attack on the identity of the minority. The reluctance of the community to help her is not merely based on religious beliefs; it is a defensive reaction against a state that they perceive as being hostile. At the same time, the film also undermines the “saviors.” The lawyers and politicians who are supporting her are portrayed as having their own agendas. Subtly, Haq insinuates that for most of the majority, Shazia is merely a convenient target to vent their anger at a minority religion.

Judicial Verdict vs Legislative Competence

The climax of Haq is not the judicial verdict itself, but the political implications that follow and resemble a structural commentary on Indian democracy. The movie builds tension towards the Supreme Court’s decision, which is portrayed as a triumph for constitutional morality. The judiciary is shown to be the last hope, where the law is read through the prism of justice, not scripture. The judges’ reluctance to be swayed by dogmatic interpretations of personal law shows the “individual conscience”. However, the movie refuses to end on this triumphant note. It takes courage to portray what follows in the wake of this judicial triumph—the enactment of the Act that watered down the judgment to suit the conservative vote bank. This act by the legislature is shown to be a betrayal of the Constitution. It reinforces the major point of the movie: that in the Indian governance equation, gender justice is the first sacrifice in lieu of electoral politics. This is a sheer reflection of the Indian public policy, which suggests that even though the judiciary can grant rights, it is only the will of the legislature that can secure them.

Conclusion

Gandhiji quoted “Poverty is the worst form of violence” but this movie clearly proves that Indignity is the worst form of violence which indirectly leads to poverty gradually and the state’s main responsibility is to protect its’ citizens from that indignity.

Ultimately, Haq illustrates that injustice not only occurs because of the lack of laws but also because of the inability of institutions to address everyday injustice, particularly when it occurs in the private and emotional realm. In doing so, the film broadens the definition of public policy not only to include formalized plans but also to everyday experience. Haq displays that Justice is not only dependent on legal equality but also on the ability of governance structures to address vulnerability as a public issue.

However, Haq is more than a historical drama about a 1980s legal battle; it is a reflection of the still suffering idea of secularism, which has no single definition. The question that Haq leaves us with is not whether policies exist, but whether they are framed to reach those whose pain is least visible. In this sense, the film challenges us to reimagine justice not as a distant legal notion, but as a function of how carefully the state listens to lives who live in silence—and whether the Constitution is the only holy book in the Republic of India.

About the Author

Akshara is a third-year law Student at the Jindal Global Law School. She has an avid interest in Financial law, Social Justice, and emerging technology. Passionate about researching and diving into untold stories.

Image Source – https://www.imdb.com/title/tt36642456/