By – K.S. Prathignya

Abstract:

This article applies a Marxist-Feminist framework to understand how marital rape unveils the reality of what bodily autonomy is regarded as in India, displaying how it inherently shapes the discourse around women’s personal sovereignty. It will argue that marital rape is used as a tool to continue the primitive accumulation of women, thereby existing as proof of this process’s existence. It will draw parallels between subaltern development studies and critiques of eco-feminism to demonstrate how primitive accumulation is a persistent logic in the spheres of legality and gender.

Introduction

Marital rape refers to the act of non-consensual sexual intercourse with one’s spouse. The perception of consent is therefore contested, which then constructs consent as a concept in various domains, including legality, history, and other social sciences. In this context, it is inhumane, as consent is not viewed as an individual, autonomous decision, but rather as a collective one. Not only is it regarded as sexual violence, but also as domestic violence, although the act itself need not inherently be physically brutal, it is still psychologically and emotionally severe. This indicates that the spouse’s rejection of sexual intercourse is not respected and is met with coercion or force.

In India, this is one of the many popular notions that leads to marital rape not being criminalised by law. However, India has criminalised rape and constructed an idea of consent that seemingly respects a woman’s bodily autonomy. Yet, the exclusion of marital rape from criminalisation arguably offers a more accurate representation of India’s attitude towards women’s bodily autonomy.

Section 375 in the Indian Penal Code classifies rape as an act committed by a man against the will and without the consent of a woman; however, Exception 2 to Section 375 does not recognise marital rape to be a punishable offence, particularly if the wife is above the age of 15. India currently maintains that it does not wish to involve itself in the private sphere or interfere in marriages. It can be argued that the discourse behind consent and women’s autonomy only exists as valid when there is no reproduction of a capitalist-patriarchal standard being disrupted. This type of dynamic is predominantly reproduced in the current institutional model of marriage.

The Construction of Consent

The earliest discourse on consent in India dates back to the colonial period, to the case of Phulmoni Dasi. Queen Empress v. Hari Mohan Maiti (1890) was an 11-year-old girl named Phulmoni Dasi being raped by her husband, Hari Mohan Maiti, a 35-year-old man.

After 13.5 hours post-rape, Phulmoni Dasi had passed away due to a ‘copious haemorrhage’. This refers to a total rupture in her uterus and a dent in her vaginal wall, resulting in a massive blood clot.

Her medical autopsy discovered that her body had not attained puberty and was unfit to participate in any sexual intercourse. Therefore, the medical verdict was that a mature male genital had penetrated and destroyed an immature female organ.

However, the court verdict was increasing the Age of Consent from 10 to 12, after debates that understood that Phulmoni Dasi was above the statutory age and that this could not constitute as ‘rape’ in technicality. Due to the humanitarian narrative being cultivated rather than a debate on technicality, the judge ruled that a husband does not have the absolute right to enjoy his wife without regard to her safety.

The final judgement was the conviction of Hari Mohan Maiti for the crime of “rash and negligent act” instead of rape or culpable homicide.

The stark juxtaposition here is the judge himself ruling with a humanitarian perspective; however, the actual conviction is completely different. Although this case kick-started the socio-legal evolution of women’s safety and bodily autonomy, what is still present is that the construction of this discourse itself is performative. If there is a progressive outlook declared on a woman’s autonomy, what stops it from being criminalised from a legal standpoint?

If the judge was progressive in their ruling, why was Hari Mohan Maiti not charged with rape or culpable homicide rather than rape?

Ishita Pande also argues that this case treated Phulmoni Dasi as an inanimate object or a fable by reducing her to a medical curiosity, displacing her from the discourse itself. Rather than highlighting the importance of this lived experience of exploitation, it became a form of proof for state-building narrative, reinforcing that this discourse is inherently performative. Exception 2 of Article 375 exists as a way for the state not to face backlash from religious groups, as the case of Phulmoni Dasi did for the Age of Consent Bill of 1891. Orthodox Hindu groups vehemently opposed this resolution as it raised the age of consent; therefore, girls could not participate in sexual intercourse at 10 instead of 12. The justification behind this backlash is why one must question — why the expense of women’s bodily autonomy comes at the expense of culture. Additionally, it raises the issue of why culture is used as a justification for such atrocities. This concern is particularly important when considering that the individual involved is not an adult woman, but a girl.

The discourse behind women’s bodily autonomy signifies “progressiveness”; however, the reality, which lies in terms of how it is legally perceived within the state, hints at primitive accumulation. Primitive accumulation refers to a historical process which originally enclosed or seized the means of production, which created a foundation for a capitalist order.

Critical Analysis

Silvia Federici, in Caliban and the Witch, talks about how women were victims of the violent process of primitive accumulation. In the Marxist-feminist framework, women’s sexuality was to be dispossessed and ‘tamed’ for capitalist reproduction, which was done through the original event of primitive accumulation, violently reorganising gender and reproduction. In the context of this book, the process was done through the European witch hunts, which created a pipeline to women and their bodies being regarded as private property.

In the context of India, rituals exist as a way to control the reality of what the legal sphere regards women’s bodily autonomy to be, despite social discourse. These rituals also control sociological institutions such as marriage, which encourage ignorance towards women’s autonomy. The proof of this discourse being performative can be proved with the existence of Exception 2 of Article 375, where marital rape is not criminalised. Phulmoni Dasi’s case is an example of this, where there was social discourse not because of genuine concern for women’s autonomy, but rather because the Colonial state seized an opportunity to advance its civilising mission ideologies.

Samir Amin argues that primitive accumulation is still an ongoing process. Primitive accumulation is an ongoing process because it is a permanent logic, through economic manipulation. In developmental studies, ecological dispossession continues to happen through law. Historically dominant countries, through colonialism, assert economic dominance through legal control over post-colonial countries. The semantic phrasing suggests that these ‘Global North’ countries are to be the saviours of the ‘Global South’, when it was the former that has and still exploits the latter to the point of these countries needing ‘development’. This continues to happen because capitalism requires new ways to dispossess resources; furthermore, there is accumulation by dispossession. There is discourse on the self-sufficiency of post-colonial countries constructed; however, the reality of it lies in how legal frameworks are structured.

However, this argument originally surrounds ecological exploitation; the same can be analysed with gender. Nancy Fraser critiques eco-feminism, which equates women to nature, such as Mother Nature. Often, this encourages notions of femininity being similar to that of the natural world, especially its reproductive qualities. Rather than focusing on ideas that show women have historically depended on the environment for their livelihoods, it is instead the symbolic reduction of what women are to be regarded as. Similarly, just as expropriation of the natural world has been normalised to the extent of the metabolic rift, the same also exists for women. Therefore, referring to Coulthard’s idea of accumulation through legal recognition, there is also primitive accumulation of the woman’s body through the basis of legal recognition being significant.

Furthermore, just as primitive accumulation is an ongoing process in the ecological world, it is also ongoing in the gendered sphere. Tying back to Federici’s arguments, this also maintains gendered divisions caused by the original enclosure itself. Therefore, marital rape exists as a tool of the maintenance of women as private property and proof of the primitive accumulation of a woman’s bodily autonomy being an ongoing process. As the foundation of this discourse will only be recognised as valid unless recorded legally, no matter what public discourse of “progressiveness” occurs.

Conclusion

Marital rape helps continue the exploitation of women in the institution of marriage, as it levies a higher burden of unpaid labour for women. In the traditional breadwinner-homemaker model, women are already the home-maker, which means participating in care labour that is unpaid and therefore, deeply undervalued. This burden is more strenuous when sexual intercourse is forced upon a woman. There is an immense emotional, physical, and psychological burden added to the already existing care labour a woman performs. Therefore, marital rape not being recognised as a crime only controls a woman’s body, by treating consent as a collective decision when not all labour is shared collectively. This inherently reinforces that women are private property in some aspect, despite whatever discourse may exist.

Authors Bio

K.S. Prathignya is a second-year student majoring in Political Science (Hons.) and minoring in Economics. Her interests include applying critical theory to examine the political economy of contextual climates, as well as how capitalism shapes public discourse in the 21st century. She is also interested in media studies and the political economy that shapes the power structures behind what we consume today.

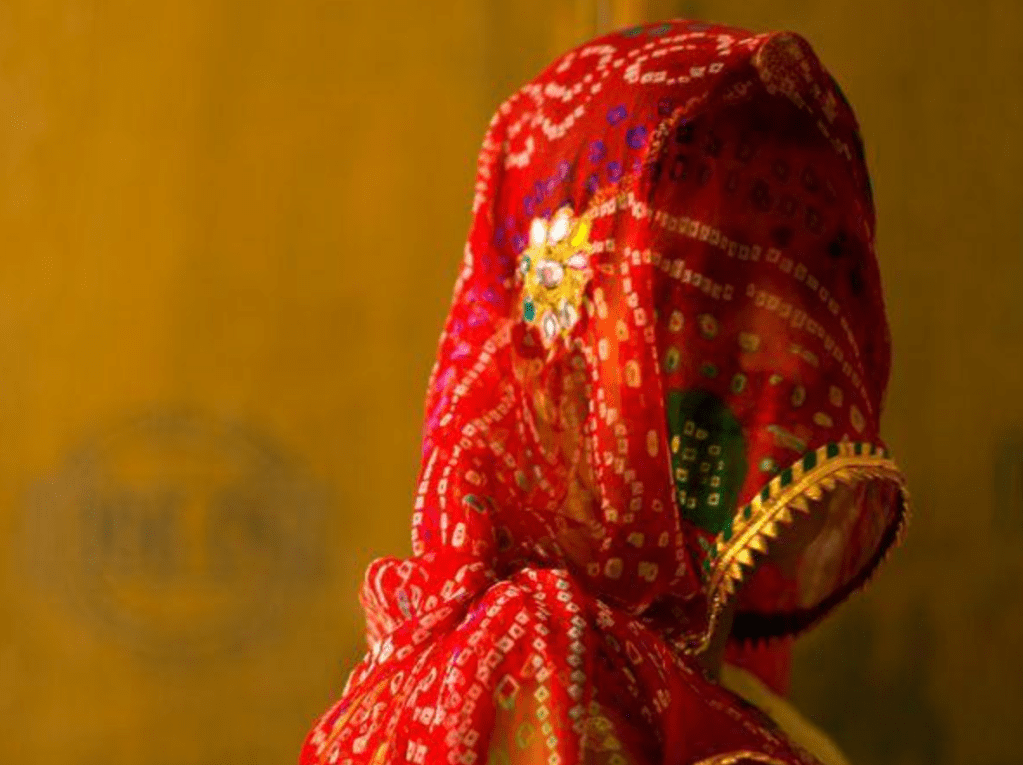

Image Source: Photo Gallery: Faces of India — National Geographic | National Geographic