By – Gauri Yadav

Abstract

This essay explores how cancel culture, once a tool for justice, now reflects the same hierarchies it sought to dismantle. Using Foucault’s theories on power and surveillance, it analyses how digital audiences act as judges in spectacles of punishment. Through case studies involving Depp, Heard, Brown, and others, it reveals the gendered and selective nature of public outrage. The article ultimately questions whether cancel culture holds power accountable or merely recycles old injustices in new forms.

Introduction

Cancel culture emerged as a digital tool that promised accountability. At its inception, it felt radical. Finally, ordinary people could call out public figures for wrongdoing. For a moment, it felt like power had shifted. Audiences were no longer passive consumers. They became active participants in shaping the reputations of celebrities, influencers, and politicians. The internet, particularly platforms like Twitter, YouTube, and TikTok, became arenas of public reckoning.

But this power soon revealed its own limitations. Cancel culture, instead of staying a tool of justice, began to mirror the very systems it sought to challenge. It became selective, performative, inconsistent and most importantly, gendered. The following article examines how cancel culture, far from being a democratic mechanism of accountability, reproduces the same hierarchies it claims to dismantle. Using Foucault’s theories on power and surveillance, it investigates the ways in which public trials are carried out not in courtrooms but through edits, comment sections, and viral clips. It shows how cancel culture has turned into a spectacle. It is not always the guilty who get punished. It is the most visible.

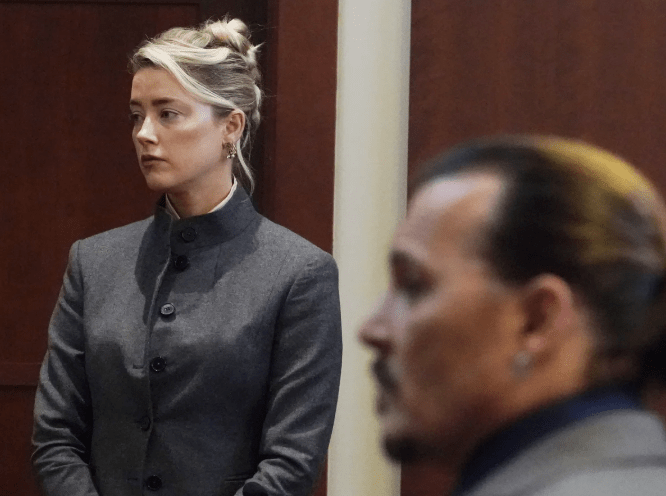

Johnny Depp and Amber Heard

The Depp-Heard defamation trial became one of the most-watched court proceedings in modern digital history. Taking place during the pandemic, it was consumed like reality television. What made this case particularly disturbing was not just its content but how it was consumed. Heard, a young actress, accused Depp, a seasoned actor, of abuse. Depp responded with a defamation suit. As the trial unfolded, livestreams were dissected in real time. Reels of Heard breaking down were turned into memes, courtroom footage was transformed into fan edits, and her testimony was reduced to soundbites. Before a verdict had even been passed, public opinion had already cast her as the villain.

The legal breach in question was defamation. However, the case also seemingly decided that Heard was never abused or sexually assaulted. This is not to say she may not have been a perpetrator too. However, the public largely painted her as the villain while portraying Depp as the quiet, abused man enduring it all. The case cost Heard significantly, including her role in Aquaman 2 and several brand endorsements. Depp also lost his part in Pirates of the Caribbean, but he held on to his Dior Sauvage ambassadorship and was celebrated as a masculine figure who had endured years of quiet suffering.

This case shows how digital audiences have become the new judges. The facts of the case were quickly overshadowed by the way they were presented. What is crucial to note here is how the trial was watched like a reality show. Livestreamed testimonies and viral courtroom clips became the knowledge people based their judgements on. Foucault’s idea of the “panopticon” where everyone is watched and corrected by social norms fits too neatly into this phenomenon. Heard’s career was not judged in law but judged in living rooms and group chats and hashtags.

Chris Brow

Chris Brown’s story is the opposite. He was convicted of domestic violence against Rihanna and has also faced other allegations, including rape and drugging. But his public image has not suffered the same way at the behest of “cancel culture”. His songs still chart, he performs regularly, people attend his shows in massive number, and continues to release music with well known artists. He was recently accused of raping and drugging a woman on a yacht in Miami. Despite this allegation, he has continued to appear in award shows, has been nominated for Grammys, and faced little to no boycotts from industry insiders. There is almost no mass cancellation of Chris Brown. In fact, many of his fans have justified his actions using strange rationales like “he was young” or “Rihanna forgave him”. This moral selective amnesia indicates that cancellation does not respond to the gravity of the crime but to the spectacle of it. Because the abuse inflicted Rihanna was not as publicly broadcasted as Heard’s courtroom cries, it did not evoke the same performative outrage.

Justin Baldoni and Blake Lively

The lawsuit between Justin Baldoni and Blake Lively offers another example of gendered narratives in digital justice. Earlier last year, Lively filed a lawsuit accusing Baldoni of sexual harassment and creating a hostile work environment. She also alleged a coordinated campaign to smear her reputation. Baldoni filed a defamation suit in return. His case was dismissed. But Lively’s reputation has continued to suffer. Social media quickly turned against her. Clips of old interviews were recontextualised and she was labelled a “pick me” girl. Her awkward moments were looped into narratives of manipulation and dishonesty. The truth of her claims seemed irrelevant. The meme had already taken over. This incident demonstrates how easily the power of storytelling gets hijacked. When a woman raises serious allegations, the response is not empathy but mockery. The trial continues in court. But the verdict online has already been delivered.

Priyanka Chopra and Shah Rukh Khan

Looking at things closer at home, during the early 2000’s there were rumours of an affair between Priyanka Chopra and Shah Rukh Khan, during the filming of “Don 2”. Despite the fact that Khan was married himself, it was Chopra who was framed into the narrative of the “homewrecker”. An inflow of biased information in the form of articles, newspaper reportings and even interviews came into the picture, all where Khan was revered and Chopra vilified. Her career in Bollywood stalled. She was reportedly blacklisted and moved to Hollywood. Years later, it came to light through various sources that she had been ostracised not because of professional incompetence but due to her personal associations. Khan never faced any consequences and his image remained intact. He continued to be revered. Chopra, on the other hand, had to reinvent herself in a new industry. This episode reveals the gendered dimension of public judgment. A man’s infidelity becomes gossip. A woman’s becomes her downfall.

Analysis

Foucault argues that knowledge is produced through power. It is not neutral but rather constructed. It serves someone. Cancel culture shows how this operates in the digital age. The knowledge we have about Heard, Brown, Baldoni or Chopra is not shaped by facts alone. It is shaped by who has the power to shape the narrative. In his book, Discipline and Punish: The Body of the Condemned, using the brutal execution of Robert Damiens, Foucault highlighted that form of punishment is a spectacle which is meant to reinforce the absolute power of the monarch and instill fear in public. Earlier, executions were highly ritualized, which demonstrated both the suffering of the criminal and the power of the state. Today, cancel culture is highly publicized, showcasing that power is still in the hands of the capitalist classes controlling the masses and punishing those who deviate.

The core issue revolves around the selective nature of accountability that is offered. Although Heard was both a victim and perpetrator, her story got distorted to be a complete villain despite never being convicted of the offence of abuse. However Brown, who was not only convicted of abuse once but multiple times and has been charged with rape, continues to flourish. Similarily, despite Baldoni’s claims of defamation being dismissed, Lively’s accusation of sexual harassment is not taken seriously. This disparity speaks to Foucault’s deeper point that truth is produced through systems of power. The law did not save Heard’s image even though it did not convict her of abuse. Because the court of public opinion had already decided. That court does not rely on testimony or facts. It relies on what generates the most traction. Brown’s legacy was never put under trial by social media in the same way. His crimes became old news. But Heard’s perceived hysteria and her crying face frozen on thousands of Instagram reels became the knowledge people held. It was edited and looped and watched millions of times.

This new system of surveillance does not require the state. It requires attention. People watch each other. People punish each other. But they do not always punish the worst offenders. They punish the easiest targets. The truth is, no article can truly capture the experiences of the many women who are constantly pitted against one another, while the issue often centres around the man. These situations are far too common, whether it is Selena Gomez, Hailey Bieber and Justin Bieber or Jaya Bachchan, Rekha and Amitabh Bachchan. Women are subjected to far greater scrutiny because the standards imposed on them are higher. Men, in contrast, have always been allowed to make mistakes, even when those involve sexual harassment. For women, even something as basic as loving someone can be turned into a weapon. These stories are always framed as women fighting women. The man in the middle quietly fades from view. The conflict becomes entertainment and the power imbalance remains hidden.

Conclusion

Cancel culture no longer functions as a tool for progressive accountability. It now operates as a spectacle of punishment controlled by internet virality. This form of public accountability is not guided by facts or law but by the manipulative use of images and soundbites. Foucault reminds us that knowledge is not innocent. It is always linked to regimes of power. The knowledge we have of Heard and Brown and so many others is not a reflection of truth. It is a reflection of the politics of attention. What trends get seen and ultimately become the truth used to silence. In the end we must ask who is really being cancelled? Is it the powerful? Or is it the ones whose characters and morality is easier to assassinate?

Author’s Bio

Gauri Yadav is a fourth-year BA LLB Honours student at Jindal Global Law School. She is passionate and keen on the subjects of Jurisprudence, Gender Studies, Sociology and Constitutional Law.

Image Source : https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/dec/19/amber-heard-johnny-depp-legal-settlement