By – Muskan Hossain

Abstract

Throughout the course of history, women’s voices have been silenced, controlled and dismissed- whether through the demoralisation of ‘gossip’ or the policing of ‘TMI’ (too much information). Gossip, once a term with positive connotations signifying sisterhood, has now been rebranded as deceitful in order to suppress female autonomy, as can be seen in events like the Salem Witch Trials. Today, women’s voices are still silenced when talking about personal struggle or challenging societal norms. By reframing gossip and oversharing as tools of resistance, this article aims to reclaim these narratives to challenge existing norms.

Introduction

Ever since history can be traced, it is undeniable that women’s words have been marketed as malicious. Whether shared in privacy with their friends, or declared publicly, their voices have been controlled, or at the very least, taunted. From the female branding of ‘gossip’ during the medieval times, to the policing of ‘TMI’ (too much information), the silencing of female voices has been a deeply ingrained social norm. What is it exactly about women’s voices that make them so threatening? And why is it that gossip, which has often been used for survival and solidarity, has been demonised for centuries?

The Journey of Gossip: From Sisterhood to Sin

Historically, the word ‘gossip’ had positive connotations to it, and was not underlined with negative connotations. Dating back to the 12th century, it was used to refer to a close relative- someone like a godparent, or sibling. It later expanded to someone who was a close friend to you, someone who may be present with you during moments of vulnerability. In general, it was a term signifying sisterhood and trust.

Then how is it that a word as such is now used as a taunt towards women? The answer comes forward in the 17th century, when it was reclaimed to be used in the capacity that we know of now. As women’s spaces became viewed as potential sites of resistance, patriarchal forces aimed to strip the power of this word, which made it take a darker turn. Sylvia Federici, in her book Caliban and the Witch (2004), argues that the demonisation of women’s speech was part of emerging capitalist societies’ larger efforts to undermine female autonomy and communal solidarity.

This fear of communication between women can significantly be seen in the Salem Witch Trials which took place from 1692-93, where it played a vital role as accusations were often based on whispers and secondhand stories. Testimonies given by women- especially when they were contradicted by male authorities- were deemed untrustworthy and even malicious at times. The story of the trials began when young girls in Salem, Massachusetts, started accusing women of witchcraft. As these rumours spread through ‘gossip’, it led to the execution of at least 20 people. Further, women who were outspoken or deviant from social norms were more likely to be targeted, which further reiterated the idea that women’s words are “dangerous”.

The Politics of ‘Too Much Information’

In “contemporary” society, women’s discussions about health, sexuality, or personal struggles are often met with discomfort or dismissal. The very concept of ‘too much information’ (commonly abbreviated as TMI) has evolved into a modern mechanism for deriding women’s experiences. Everything from menstruation to postpartum depression is brushed aside when included in conversations, deemed inappropriate or excessive.

A notable example is the public reaction to Meghan Markle’s disclosure of her mental health struggles during an interview with Oprah Winfrey. When revealing her harmful thoughts during pregnancy, she attracted criticism rather than compassion. Instead of empathy and support, she was met with dismissal of her pain, her revelations labeled as attention-seeking or manipulative. Such a response begs the question: Would the response have been the same if Prince Harry had shared similar vulnerabilities? He likely would have been praised for his bravery in admitting such a difficult situation. This discrepancy reinforces the notion that when women speak openly about their suffering, they’re perceived as attention seeking rather than understanding.

This pattern is evident in movements like #MeToo, where survivors face criticism for saying “too much” and are blamed for allegedly ruining their abusers’ reputations instead of being acknowledged for attempting to break cycles of systemic abuse. The recent case of 24-year-old gynaecology student Ruben Vantisphout, who was allowed to walk free despite being proven guilty because he had “good grades” and a “promising future,” exemplifies how framing conversations around such incidents as excessive serves as a deliberate tactic to discourage women from voicing truth.

The Stigma of Talkative Men

While gossip and ‘TMI’ are used to demean women, “talkative men” do not escape social scrutiny either. Men who are naturally verbose or enjoy engaging in gossip are often viewed as failing to conform to traditional ideals of masculinity. They are frequently characterised as weak, overly sensitive, or “feminine.” This demonstrates that ridicule toward gossip is not merely a gendered tool of suppression but also one that enforces rigid gender roles where men must remain stoic and authoritative while women are expected to be silent and restrained.

Deborah Cameron, in her book The Myth of Mars and Venus (2007), explores how societal gender norms shape language use, demonstrating that men who speak in emotionally expressive or “gossipy” ways face ridicule for transgressing typical masculinity standards.

The Salem Witch Trials provide another historical example. While most victims were women, men who supported them or opposed the trials were also targeted. John Proctor, one of the few men accused of witchcraft, was executed partly because he openly criticised the court and its hysteria. His fate exemplifies how challenging traditional gender roles—whether as a vocal woman or a dissenting man—could have severe consequences.

The Weaponization of Stereotypes

One way misogyny against women’s speech persists today is through humor. Jokes about women gossiping permeate pop culture, stand-up comedy, and everyday conversations. Phrases like “Women can’t keep a secret” or “She’ll talk your ear off” diminish the importance of women’s communication and reinforce the stereotype that their words lack substance or value.

These jokes are far from innocent; they contribute to a broader cultural perception that women’s discussions are trivial and unimportant. When a woman shares significant or sensitive information, it is often dismissed as mere gossip. This extends beyond humor—in professional settings, female employees’ ideas are frequently taken less seriously, whereas male colleagues engaged in similar discussions are perceived as authoritative or strategic.

Gossip as Resistance

Despite its negative connotations, gossip has long served as a form of social resistance. Enslaved Black women in the American South—as discussed in Stephanie Camp’s Closer to Freedom—used gossip networks to warn one another of potential threats, plan escapes, and rally against their oppressors. Similarly, in many conservative societies, gossip has been the only avenue for women to communicate about reproductive health, legal rights, and domestic abuse.

Even in modern times, platforms such as TikTok and Reddit provide spaces for women to freely discuss issues that mainstream narratives dismiss. The rise of online feminist discourse, where women share their experiences and insights through storytelling, demonstrates that gossip can still effectively raise awareness and empower people.

Why Are We Afraid of Women Talking?

The fear of gossip and ‘TMI’ stems from anxiety about women controlling their own narratives. The ability to share personal experiences, particularly among women, fosters informal knowledge networks capable of challenging established power structures. This poses a particular threat to those who benefit from maintaining the status quo. Controlling women’s speech has historically served to limit their autonomy by silencing their ability to organize, warn, or resist oppressive conditions.

When women talk to one another, they are not merely chatting; they are exchanging crucial information about their rights, safety, and collective struggles. The labeling of these conversations as frivolous or excessive serves as a form of social conditioning, causing women to hesitate before speaking up. If their words are dismissed as gossip or oversharing, their credibility suffers before their message is even considered.

Furthermore, women’s public discussions are heavily policed because they force society to confront uncomfortable truths about sexism, abuse, mental health, and inequality. The dismissal of these conversations as ‘TMI’ is more than just enforcing social norms—it is a deliberate act of censorship that prevents women from changing the cultural narrative. When stories about workplace harassment, reproductive health, or domestic struggles are labeled as “too much,” they discourage transparency and perpetuate systemic injustices.

By labeling women’s speech as excessive or irrelevant, patriarchal structures ensure that their voices remain marginalized. Categorizing certain speech as gossip or oversharing is about power as well as decorum. Who gets to speak? Who is to be believed? And who gets to be dismissed? The answers to these questions demonstrate how deeply entrenched societal biases continue to determine which stories are deemed worthy of attention.

Conclusion

It’s time to reconsider how we perceive women’s speech. Instead of viewing gossip as a threat, we should recognize it as an informal network of knowledge and safety. Instead of dismissing ‘TMI,’ we should honor it as an act of bravery in a world that thrives on silencing women.

Women’s voices have been burned at the stake, erased from history, and mocked in the media. Yet they have persisted. When someone refers to a conversation as ‘gossip’ or dismisses a woman’s story as ‘TMI,’ we must consider who benefits from the silence. What essential truths are we being kept from hearing?

Author’s Bio

Muskan Hossain is a second year student pursuing a BA (Hons.) Liberal Arts and Humanities, at OP Jindal Global University. An avid reader, and an aspiring journalist, she has a keen interest in gender studies, culture, and political theory, and aims to explore the intersections of tradition and modernity in contemporary India.

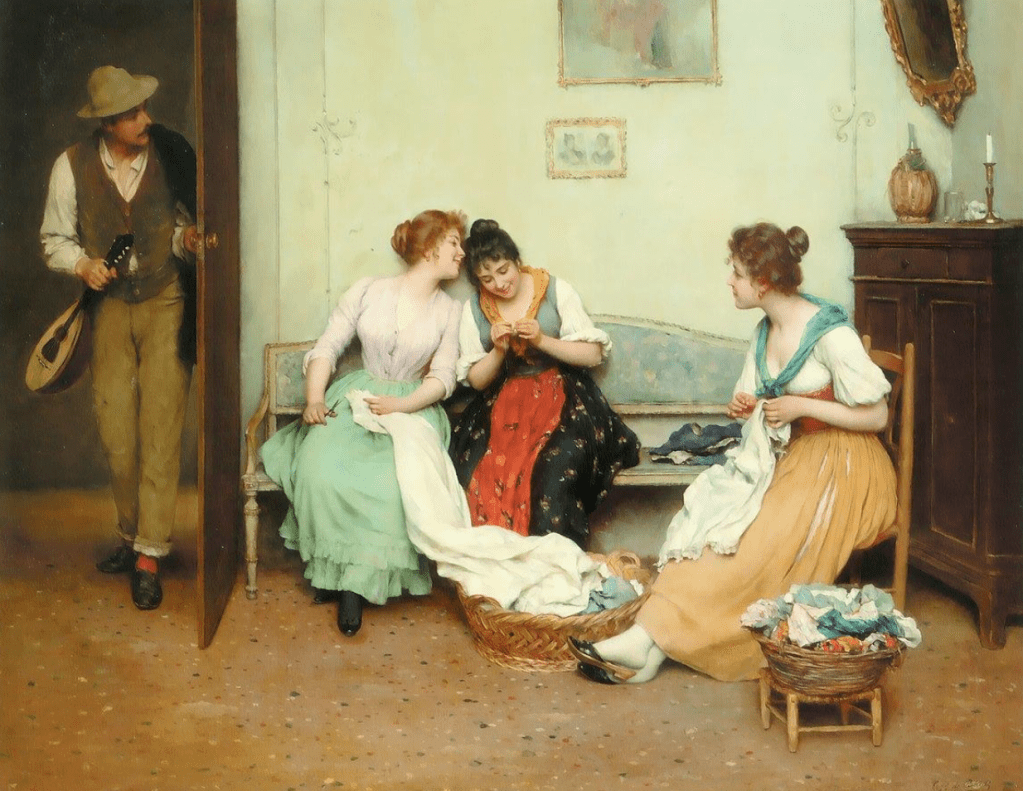

Image Source : https://retrospectjournal.com/2024/11/17/is-gossiping-feminist-the-history-behind-the-villainisation-of-tell-tales/