By Vaidehi Sharma

Abstract

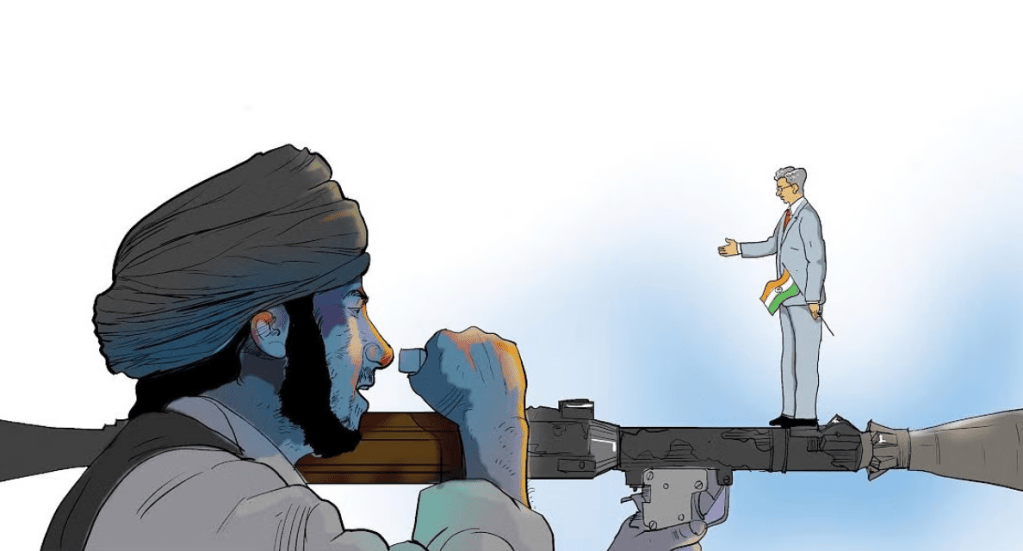

The recent meeting between Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri and Afghanistan’s Acting Foreign Minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi, on January 8 has set the stage for active high-level engagement between India and the Taliban. However, the meeting comes at a time when the Taliban is continuing its brutal crackdown on women’s rights. This article aims to assess the implications of increasing engagement between the Taliban and India, a country that constantly presents itself as a supporter of Nari Shakti and Women’s Empowerment.

Introduction

In a first, India’s Foreign Secretary Shri Vikram Misri met the Acting Foreign Minister of Afghanistan, Mawlawi Amir Khan Muttaqi, on January 8, 2025. This meeting, held in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, marked the highest level of political engagement between India and Afghanistan ever since the Taliban came back to power on August 15, 2021.

Such bilateral engagement with Taliban 2.0, though unprecedented, is not a surprise. India’s foreign policy towards the Taliban is based on pragmatic considerations of national security and regional power dynamics. The meeting is simply a step forward—a big one at that—in India’s careful, cautious, and steady engagement with the controversial regime. For the Taliban too, engaging and strengthening ties with India is beneficial to secure humanitarian aid, diversify its ties, and overcome international isolation. However, this boost in bilateral relations runs parallel to the slaughter of women’s rights in Afghanistan.

The Taliban continue to institutionalise blatant gender discrimination, placing overbearing restrictions on women’s rights—including education, employment, and movement—with no signs of stopping. Afghanistan has practically erased women from public life and has caused a human rights crisis. In light of the gender apartheid proliferating in Afghanistan, the rendezvous of top delegates from India and the Taliban, showcasing clear acknowledgment of the Taliban rule by India, can have myriad implications for the fight for the freedom of women in Afghanistan, as well as for India’s international image as an advocate for gender justice.

This article aims to understand India’s strategy in its expanding engagement with the Taliban and what it means for India’s stance on the worsening rights violations prevalent under Taliban rule.

History of India’s Engagement with the Taliban

While relations remained bleak during the Taliban’s first rule from 1996–2001, bilateral engagement proliferated after the United States established an interim government and ousted the Taliban in 2001. In the period between the first and second Taliban rule, India was one of the biggest contributors to Afghanistan’s growth through humanitarian, infrastructural, and other development projects. India showed keen interest in helping Afghanistan establish a “non-aligned and fully representative post-Taliban regime.” Hence, it is obvious that the return of the Taliban was a cause of concern for India. Along with the rest of the world, India also disengaged from Afghanistan.

Post the Taliban’s return, although the Taliban wished to retain ties with India, India has been apprehensive. India does not officially recognise the Taliban rule. The former spokesperson for the Ministry of External Affairs, Arindam Bagchi has previously expressed concern over the Taliban’s ban on women attending universities and the lack of women in its Cabinet. Similar concerns regarding the exclusion of women from public life, the lack of an inclusive government, and the threat of violence against them were expressed by Ambassador R. Ravindra, India’s former Deputy Permanent Representative at the United Nations Security Council. Additionally, India has delivered humanitarian assistance to “the people” of Afghanistan, along with sending an official delegation to oversee these efforts. However, since 2023, the Afghan Embassy in New Delhi has ceased to operate, showcasing a lack of diplomatic connection.

Interestingly, in 2025, as evidenced by the meeting between Vikram Misri and Mawlawi Amir Khan, India has expanded its focus from the “people” of Afghanistan to the political authority of the country: the Taliban rulers.

The meeting signals a clear intention from both sides to promote bilateral relations. The two sides discussed ongoing humanitarian assistance programs for the Afghan people and the possibility of future development projects. Restarting the issuance of visas for Afghans was another significant topic discussed. They also discussed trade and commercial relations and agreed to promote the utilization of the Iranian Chabahar port. India also voiced its security concerns, to which the Afghan side was receptive. Additionally, both sides discussed boosting ‘sports cooperation.’ Most importantly, both parties have agreed to future engagement, committing to “regular contacts at various levels.” By doing so, the meeting has paved the way for more political exchanges between the Government of India and the Taliban leadership, involving high-level delegations from both sides.

India’s Current Interests in Afghanistan:

India’s engagement with top officials of the Taliban reflects its very practical concerns. India is seizing the opportunity to improve its relationship with Afghanistan while its relations with Pakistan remain tense because of militancy concerns, specifically due to Pakistan’s worry that Afghanistan is harbouring members of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan.

By employing the Chabahar port, trade between Afghanistan and India can flourish without depending on Pakistani trade routes. By boosting developmental and humanitarian projects, India wishes to be an important player in Afghanistan, thus counterbalancing and reducing Pakistan’s influence over the Taliban-ruled state. By solidifying friendly relations with Afghanistan, India will be in a better position to counter its hostile neighbours, which is especially important considering China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Before the Taliban came to power for the second time, India had contributed around $3 billion to development projects in Afghanistan. It will be economically fruitful for India to not let that investment go to waste by boycotting Afghanistan but rather continue engaging with the country and boost its soft power in the region. Engagement is also important so that Afghanistan cooperates in ensuring that it does not become a safe haven for terrorists and anti-India militants.

For Afghanistan, India’s aid, assistance, and investment, along with trade, will not only help its struggling economy but also prevent it from becoming overly dependent on Pakistan and help it counter Pakistan’s strong influence. However, most importantly, engaging with countries like India brings it closer to what every new ruling power needs: legitimacy.

Afghanistan’s style of governance has received international backlash and condemnation. No country has recognized the Taliban government. Political and economic isolation by powerful countries obviously doesn’t do its already weak economy any good. In such a situation, Kabul needs to establish diplomatic relations with as many key players in its region as it can. As countries like India engage with the Taliban, it brings the regime one step closer to international acceptance or at least condonation.

However, although both India and Afghanistan will benefit from an increase in high-level engagements, their rapprochement sits uncomfortably with the reality of the threat to the life and freedom of Afghan women.

Engagement with the Taliban and Concerns for Women’s Rights: Walking a Tightrope?

On March 8, the Taliban issued a statement claiming that the rights of Afghan women were secure “in accordance with Islamic law.” However, it is widely acknowledged that the Taliban have forcibly imposed their interpretation of Islam on the country’s entire population. The Taliban has institutionalized gender discrimination and, through systematic restrictions, has confined women to their homes.

The Taliban’s deeply problematic Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice Law places the responsibility on women to hide their faces and entire bodies from every man who is not a close relative. Women must also conceal their voices when outside their homes. In addition, through various orders, the Taliban has banned employment and education beyond the sixth grade for women. Women are restricted from traveling and using public transport without a male guardian. These restrictions are brutally enforced through violence, torture, detention, and forced disappearances.

International condemnation and isolation have undoubtedly had a detrimental impact on Afghanistan’s economy. A poor GDP, escalating hunger, food insecurity, and widespread poverty and unemployment have put the Afghan population in a precarious position. Conditions will only worsen if the Taliban continues to lock away half of its population and potential labour force. However, the economic loss is apparently not enough to deter the Taliban from its oppressive measures. It is important to understand the implications of India-Taliban engagement in this very context.

India presents itself as the world’s largest democracy and an ardent supporter of women’s rights. Nari Shakti has been at the forefront of the central government’s agenda for many years and has garnered a lot of acclaim. Under this agenda, the Prime Minister has, on several occasions, emphasised the programmes and laws enacted by the central government to promote women empowerment, along with his government’s support for women-centric and women-led development, diversifying their opportunities, promoting financial independence, and ensuring their active participation in the democracy.

Though India is far from officially recognizing the Taliban regime, high-level meetings between top officials of both countries grant the Taliban something uncomfortably close to legitimacy. Granting legitimacy to the regime risks sending the message that India tolerates the horrible treatment of women in Afghanistan.

If India shifts its foreign policy towards Afghanistan from minimal political interaction to active and robust engagement with the Taliban regime, such “normalization” of relations risks undermining not only the gravity of human rights abuses in the country but also India’s image as an advocate and defender of human rights.

It would be accurate to say that India is walking a tightrope: on one hand, it needs to engage with the Taliban to secure its regional and security interests; on the other, it does not want to recognize or legitimize the Taliban’s rule and its actions because, among other things, doing so would signal that the rights of women are of little concern to India.

Conclusion: What India’s Stance Is and What It Needs to Be

India and Afghanistan have laid the ground for active future engagement. Bilateral relations with Taliban 2.0 are still in their nascent stage, and it is important how India approaches their advancement. India needs to reiterate and make its stance clear: its engagement with the Taliban is due to the fact that they are the de facto rulers of Afghanistan and in no way signifies support, acceptance, condonation, or tolerance of their treatment of women or the restriction of their rights. India must use its engagement—and any leverage over the regime—to push for the lifting of bans on education and employment.

It is pragmatic for India to maintain good ties with Afghanistan; however, its future policy must also reflect unwavering support for women’s rights.

Author’s Bio

Vaidehi Sharma is a second-year BA LLB student at Jindal Global Law School.

Image Source: https://www.deccanherald.com/india/cosying-up-to-taliban-the-india-way-3288325