By Nidhi Ashok

Abstract

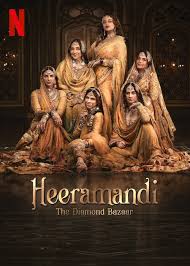

Heeramandi was a much anticipated Netflix Original Series that aimed to showcase the lives of the courtesans in Lahore in Colonial India. While the show aimed to take the audience back to the 20th century, the underlying themes portrayed through it are still relatable in contemporary times. This article seeks to identify these themes and demonstrate that these are experiences shared by women of the past and present. Further, the article aims to show that the whimsical fiction created by Bhansali and modern-day society is , in many ways, truly not that different at all.

Introduction

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Heeramandi promised viewers a peek into the lives of the courtesans in Imperial India in the 1920s. Set against the backdrop of the historic city of Lahore, the Netflix Original Series grapples between portraying lavish lifestyles while also delving into the authentic struggles of everyday realities. While the series aims to represent a section of working women of a bygone era, the echoes of its significance are still felt in contemporary society. Heera Mandi or the Diamond market was a red-light district at the very heart of the city of Lahore. It is currently one of the largest red-light districts in Pakistan and the pressure of cultural and religious norms in Pakistan has also burdened it with the status of the largest taboo in the region. While the academia on this region and its ramifications on gender perceptions are scant, Bhansali affords the audience a glimpse into the intersecting identities of these Tawaifs as dancers, women and informed citizens of a nascent India. The show is one of paradoxes, portraying these women as not only part of an empowered and wealthy society but also a marginalised community.

The Stereotypical Portrayal of Women

The series’ significance is not just rooted in its history and characters but is exemplified by what it means for the world of cinema. Heeramandi is part of a growing wave of cinema that has opted to depart from Bollywood’s traditional oversimplified roles for heroines. It is rather a piece that is undeniably female-centric and consequently provides a nuanced and multifaceted view into the identities of women as not just fawning damsels but as individuals with opinions, dreams and unique experiences. The characters that women usually portray on the big screens are usually role-specific and their communicative space is restricted to conversations about the men in their lives. While Heeramandi’s plot transcends these constraints through dramatic tussles for power, rivalries between the Tawaifs and participation of the Tawaiifs in the freedom struggle against the British, it undoubtedly conforms to tradition as the romance blooms between Alamzeb and Tajdar in the film. Making decisions has also been a man’s profession in cinematic and real – life roles. This fact has not been revolutionised in Heeramandi but the show represents the delicate facade that at first glance portrayed these Tawaiifs as influential protagonists and subsequently their dependence on the men in power is revealed. Heeramandi in many ways functions as a mirror to the film industry at large. While there has been an uptick in women-driven casts which heralds a welcome change, the reality is the dearth of women working as film technicians in India. The disproportionate sex ratio of students and teachers in the Film and Television Institute of India shows the significant challenge the Indian film industry is still yet to overcome.

Women and Gendered Spaces

The setting of the show is also significant in deconstructing gendered spaces. Spatial arrangements have been described as functioning as a canvas upon which gender and power dynamics are first imprinted and subsequently maintained through encounters. In essence the setting of Heeramandi allows the audience insights into the complicated web of identities adopted by its denizens while also affording an opportunity to conceptualise such spaces in contemporary society. While Heeramandi does a great job at portraying the unusual autonomy and power afforded to the privileged class of courtesans in Lahore, it is also imperative to observe their limitations in taking up room in the urban space conceptualised by Bhansali. The limitations that women face when interacting with predominantly male-dominated spaces are not just restricted to dramatic cinema but a part of the very fabric of everyday communities. Bhansali’s imagined space reveals the harassment and exclusion women are forced to confront but also the perpetuation of the stereotype that a woman’s place is in the home. Lahore’s social landscape thus serves as a metaphor for the manner in which social norms and stereotypes influence the very fabric of urban spaces all over the country. It is impressed upon women to have a reasonable excuse to step into the public sphere and to do so only in the presence of other women. What is also demonstrated through this precarious balance of autonomy and exclusion is that the experience of women as a community cannot be understood in a singular sense. The autonomy afforded by class is also hindered by the exclusion mandated by gender. Urban spaces are not just important in identifying the imposed limitations of gender but also in witnessing the interplay of various socially constructed identities to form a comprehensive view of the diversified experiences of women.

The Male Gaze

The male gaze as defined by Laura Mulvey refers to the portrayal of characters in visual media from a heterosexual male perspective. This perspective in application reduces female characters to objects of desire, reinforcing the traditional representation of women in film. The very prospect of having a cast of women who play the roles of courtesans in Heeramandi is a shining illustration of a historic stereotype playing out in modern – day practice. The Tawaifs that dominate the stage in Heeramandi with stunning performances and a cornucopia of riches in essence attribute their wealth and status to the patronage of the powerful men that desire them. The courtesans capture the screens as luxurious figures, adorned in ornate clothing, and enviable jewellery, and often indulge in bathing in milk and flower petals. Within the fictional sets of Lahore and in the contexts of reality they are women or represent the feminine collective that must cater to a male audience. Despite the progressive themes in the film and the strides made by Bollywood as a whole to reverse the male gaze, it is still part of not only cinema but visual culture as a whole. While one of the significant effects of the male gaze is the propagation of unrealistic beauty standards, the community of women who came together to celebrate their curves and stereotypical imperfections in response to Aditi Rao Hydari’s Gaja Gamini walk in the film was a hopeful indicator of change in this regard. Hydari’s performance resonated deeply amongst the women collective thereby leaving ample space to redefine beauty independent of the male gaze. The intention to further the growing trend of body positivity in contemporary society was also beautifully portrayed in the casting of the film which saw women of diverse sizes and ages.

The Paradoxical Veil

In the midst of the stunning performances and breathtaking scenes, Heeramandi, like many other period pieces, dresses up their women in elegant outfits that include a traditional veil. Meyda Yegenoglu stated, “There is always more to the veil than the veil”. There has often been controversy regarding the significance of a veil. While some have seen it as a bar on the expression of sexuality, others have seen it as a reclaiming of female space and gaze. As a social symbol, a veiled woman reflects different conceptions of female modesty. The purdah system is also not a stranger to contemporary society and the implication of women being “invisible” especially in public spaces is still in practice today. The hailing of colonialism in India reinforced the purdah system because Indian patriarchs feared the influence of the West on their women. It was thus consequently seen as a means to help maintain control over women who were seen as a man’s property. As a result, women were not allowed to gain the benefits of Westernisation including education and inclusion in job opportunities. Bhansali through his portrayal of women has unshrouded this metaphorical veil and its implications on Indian women. The courtesans wear veils when they enter the public sphere and also when they perform for a male audience. It could be argued that this is to propagate a semblance of stereotypical feminine modesty or as a rebellion against these very stereotypes. The use of the veil in Heeramandi, just like in reality, reveals two contrasting ideas. Perhaps the right answer is that there is no right answer. The contrast and the confusion, the conformity and the rebellion, are both key aspects of the status of women today. The veiling of women can operate as both shackles and liberation. Women almost a century later are still stuck in this paradoxical limbo under the cover of this metaphorical veil. That is to say, the veil inherently could embody this paradox felt by women and open the doors to viewing women’s rights and gender equality as an unfinished project, with strides made in step to growing chasms of disparity.

Conclusion

Bhansali’s Heeramandi is not just relevant because it entertains but its inherent value is in connecting themes of the past to issues of the present. Cinema has been a useful tool to portray society in all of its diversity, shortcomings and modern advances. Whether it is a gross misrepresentation of women or a powerful social commentary on their rights, the true epilogue of every meaningful cinematic creation is the discourse it helps to create. It is society’s critique and consequent exchange of views that lends it its ability to constantly reinvent itself. Heeramandi has proven itself to be not just a social commentary but a catalyst for introspection to look into the past to envisage a better future.

About the Author:

Nidhi Ashok is a third-year law student currently studying at Jindal Global Law School. She is an advocate for women’s rights and is on a journey to constantly inform and involve herself in creating an equitable society.

Picture Credits: https://media.netflix.com/en/only-on-netflix/81122198